8.1.25 — Officially Stylish

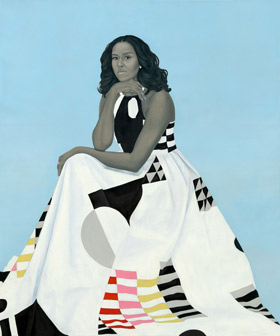

Amy Sherald became one of the most celebrated African American artists by painting one of the most celebrated African American women. It does credit to both women, her and Michelle Obama, as stylish and official. Which woman did more to create an image for others to admire?

If a portrait does the job well, it may never be easy to separate the artist from the sitter, the dancer from the dance. I wrote about the now popular painter twice before, on her delivery of the Obama state portrait and again with a fair survey of her work at her gallery. Much as I want to respond to so inviting a show as her midcareer retrospective at the Whitney, through August 10, my second past review really does say it all. Nor is this a black artist’s only display of innocence,  sophistication, and sheer pleasure in one and the same portrait. So I also wrap this into past reports on John Dowell and Jordan Casteel, with their own monuments to African American portraiture and history, and invite you to read more. Sherald has refused to allow her own show’s planned second stop, at the National Portrait Gallery, calling the decision to “contextualize” her portrait of Obama in line with Donald J. Trump’s outrageous wishes, as censorship.

sophistication, and sheer pleasure in one and the same portrait. So I also wrap this into past reports on John Dowell and Jordan Casteel, with their own monuments to African American portraiture and history, and invite you to read more. Sherald has refused to allow her own show’s planned second stop, at the National Portrait Gallery, calling the decision to “contextualize” her portrait of Obama in line with Donald J. Trump’s outrageous wishes, as censorship.

People do not often swoon over official state portraits, least of all followers of art. It would be like swooning over someone else’s yearbook photo—or a gold star from the world’s primmest teacher. Yet here they were, portraits of Barak and Michelle Obama making the news. Visits to the National Portrait Gallery soared, and (as you can see from the link) I swooned a bit, too. The portraits arrived just as an awful lot of people were longing for leaders with intelligence and a conscience, rather than just a certain orange president. People longed, too, for voices with authority to speak for them.

Oh, and then there were the artists, Kehinde Wiley for the former president and Sherald for his first lady. Wiley had appeared in galleries and museums before, often at that, for decorative, flattering, and frankly shallow portraits of African Americans off the street, all but exclusively young, aggressive, and male. He takes pride in his subjects, but with little hint that black lives matter and are at risk. Had he finally risen to the occasion, or had the occasion descended to him? Sherald, far less visible at the time, may offer a clue. Her latest portraits, much like Wiley’s in the past, stick to moments of leisure and to friends.

Her mega-gallery also has a group show that thrusts human sexuality at once in your face and behind a veil, with artists including Paul McCarthy, Paul Mpagi Sepuya, and Mira Schor. Sherald does not. She makes desire so childlike that she adapted a famous photo of a kiss in Times Square at the end in World War II. Downstairs comes an older African American, Ed Clark—better known for his place in Abstract Expressionist New York and, quite possibly, the very first shaped canvas. Work since 2000 transforms even the purest of abstraction into glimpses of clouds and sky. For the gallery’s fall 2019 opener and again for a Whitney retrospective in 2025, lavish brushwork looks back to the most gentle and glorious of summer afternoons.

Sherald feels the warmth, too, even as the real air grows cold. Four bathers, the women on the men’s shoulders, enjoy the sand and a near cloudless sky. Who is to say which earns the painting its title, Precious Jewels by the Sea? A young black man sits high in a clear-blue sky, his butt on one girder and his back against another. Sherald took for inspiration a famous shot of workers at lunch, but this guy is neither dressed for work nor short of time. With just eight paintings at her gallery, for once a hot artist ignored the pressure to churn things out, so you could relax, too.

For Sherald, attention to friends does not preclude a leap of imagination. As a self-portrait has it, When I Let Go of What I Am, I Become What I Might Be. Some pretty tart colors share space with that sky blue. She has room for reality all the same, from a handsome young man to the overweight “girl next door.” Like Michelle Obama in her portrait, large central figures stand out against fields of color, almost like playing cards. They also share contrasting paint handling in figures, clothing, and backgrounds—to play degrees of realism against one another and to keep the surfaces alive.

Backgrounds are totally flat, but with wild swings in color from painting to painting. Flesh is well-shadowed, but not in the interest of anatomy or the fall of light. Faces are personalized, but not psychologically, and everything else pops to the surface, like a beach umbrella or a polka dot dress. Titles are poetic but erudite, like the recollection of Jane Austin’s Pride in Prejudice in A Single Man in Possession of a Good Fortune. The title for the construction worker, If You Surrendered to the Air, You Could Ride It, speaks to him, but also to you. If they still feel too much like pages from the style section of a Sunday paper, consider them official portraits of the girl next door.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.