Relationships Are Difficult

John Haberin New York City

Take Me (I'm Yours) and Relational Esthetics

Kai Althoff

"The museum collects things," the Jewish Museum acknowledges. "It does not generally give them away!" In the case of contemporary art, some might add, you could not even give it away.

Well, for now the museum does, with goodie bags and "Take Me (I'm Yours)." More than forty artists start their own collections, from candy and knickknacks to poetry and political statements, and then they invite you to dig in and to take one for yourself.  I arrived at a press preview expecting coffee and perhaps a lecture, but with the most high-minded of intentions. I got sucked in anyway, stuffing my pockets with what I may or may not ever use or give away. What, though, is the take-away message? Meanwhile Kai Althoff at MoMA looks even cheaper, like a thrift store, but he is not giving anything away.

I arrived at a press preview expecting coffee and perhaps a lecture, but with the most high-minded of intentions. I got sucked in anyway, stuffing my pockets with what I may or may not ever use or give away. What, though, is the take-away message? Meanwhile Kai Althoff at MoMA looks even cheaper, like a thrift store, but he is not giving anything away.

The take-away message

"Take Me (I'm Yours)" builds on a 1995 exhibition of the same name of just twelve artists, at the Serpentine Gallery in London, curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist and Christian Boltanski. Sure enough, Obrist returns as curator, together with the Jewish Museum's Jens Hoffmann and Kelly Taxter. Boltanski returns, too, as an artist, with a conical pile of used clothes and still more shopping bags, in paper to the museum's plastic. "Paper or plastic?" It sounds right out of the check-out counter at Trader Joe's—and just as virtuous. Another contributor, the collective General Sisters, brings sustainable toilet paper.

This is all about virtue, including a critique of commodities and their value, in art and in society. Museums everywhere are expanding, with new wings, new buildings, new holdings, and exhibits of private collections that may one day be theirs. Now this museum is shrinking—deaccessioning to the point of a fire sale. It begins just past the admissions desk, where Jonathan Horowitz sets up his Free Store, with the exhortation to "Leave Stuff, Take Stuff." It extends to the bookstore, where Maria Eichhorn asks for help assembling her reading list, and to much of the second floor. The guards display their usual vigilance, asking you to empty your pockets on the way in, but not on your way out.

Many of the artists have a reputation for their assault on art institutions. Down in Chelsea, Hans-Peter Feldman hangs copies after art history, some (spare me) with clown noses on faces. Here he takes the museum down a peg, or at least jpg, with snapshots of pinup girls. Martha Rosler has been holding her gallery garage sales for years. Here she photocopies ads for a fancy watch and pages from Karl Marx. A creative installation bases more than a few of the artist contributions on plain old milk crates, as white as museum walls—and yes, the museum supplies plastic shopping bags on the way in, since contemporary art is always a handful.

Others undermine museum assumptions less directly. A young woman hands out paper disks bearing the words Be Quiet, as part of a daily performance by James Lee Byars. Of course, she is not saying. Luis Camnitzer and Alex Israel address the aura of the true genius, with stamps bearing the artist's signature and lapel pins bearing his self-portrait. Is art difficult? Leather bookmarks by Amalia Ulman admit it, with They Say I'm Hard to Read.

Several others insist on politics beyond the museum. Daniel Joseph Martinez addresses nativism and the refugee crisis with emergency blankets. Horowitz may offer something, but he also asks for your choice of a next president who, at last, may not be male. "Provocations" by Gilbert & George include demands to "bar religion" and "burn that book," while Rivane Neuenschwander assembles entire panels of protest "watchwords," and t-shirts from Rirkrit Tiravanija boast that "freedom cannot be simulated." Colorful ribbons hang down, from Andrea Bowers, each with its demands as well. Jibade-Khali Huffman prefers more cryptic messages, as Sculpture for Docents, such as "America dunks while running."

Still others have a lighter touch, such as sounds from the Carlsbad Caverns by Kelly Akashi or emojis by aaajiao, sent right to your email account. Even in vanishing, though, the artists see their identity at stake—or yours. Andrea Fraser offers her services to potential employers, with as much corporate jargon as she can manage. Heman Chong supplies ID cards for "the people we've conveniently forgotten," but black on both sides. Cara Benedetto thinks of her blue books as "a bound poem in multiple voices," and Alison Knowles would like you to describe your shoes. Jonas Mekas asks for his largely unseen film to be cut, so that you can have the acetate.

Sustainable shopping

The show has its roots at the Serpentine, but its presiding spirit in Félix Gonzáles-Torres, the gay artist from Cuba who died in 1996. Allen Ruppersberg stacks photocopies of his cloud pictures, and his wrapped candies have a room to themselves, in red, silver, and blue. They have come to stand for relational esthetics. Nicolas Bourriaud coined the term to stand for art that highlights its societal context—and that opens that context to you. Take a candy: it's yours.

The show succeeds in relating that context to many another movement, from Rosler's strict politics to Fluxus. Yoko Ono is once again dispensing air from old-fashioned vending machines, for just a quarter, while Angelika Markul lets you fill bags with air, thanks to a fan. Wall text helps draw the connections, quite on top of the wall labels for individual works. It runs to headings like "property is theft" (in the original French) and to alternatives to capitalism like the "gift economy." Repeatedly, it sees those alternatives in the Internet. In fact, each heading runs its words together, preceded by a pound sign.

Has anything changed in twenty years? Has art moved any closer to a gift—or any further from an institution? It may feel like it, as you carry home your prize, but do not be too sure. The very confluence of gift bags, from the Jewish Museum and Christian Boltanski, may have you wondering where art ends and museum institutions begin. Those wrapped candies have long since become an institution themselves, much like Tiravanija's free helpings of curry in the past. Another food item, fortune cookies from Ian Cheng and Rachel Rose, descends to cliché.

The museum may be giving something away, but it is also still collecting. Now twelve artists have become forty, and they produce on average ten thousand of each work for visitors to take away. They even encourage the consumer impulse, that wish when life is too much to go shopping. Who can resist refrigerator magnets in party colors by Koo Jeong A or coffee lids by Uri Aran—not disposable plastic at all, but white concrete paperweights? Relationships are notoriously difficult, but should not you contribute, too? The whole show now comes with warnings that it may contain sexually explicit content and peanuts.

Like the wall text, works can reduce to lectures. Sondra Perry delivers a stern one on the "blue code of silence" and the "blue screen of death," a connection lost to me. Do black lives matter? Just upgrade to Windows 10. Other work feels dragged into relational esthetics against its will, like text art by Lawrence Weiner. (He does set out temporary tattoos.)

The museum promises a context of its own, in Jewish culture and New York City. I must have missed it, although Dana Awartani adapts tile patterns from Islamic art and Yngve Holen incorporates the Arabic word for sight. Its texts also waver on the Internet as a tool for democratization or surveillance. Still, it raises questions every step of the way, like that one, and it makes a great present to others or to oneself. Come winter, I may need to return for a Kleenex from Haim Steinbach or pills from Carsten Höller. So what if they are placebos?

MoMA's thrift store

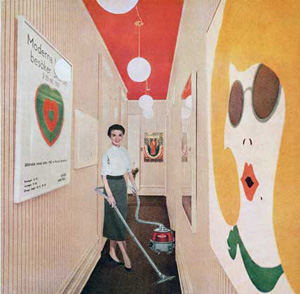

Kai Althoff would like to make a statement, if only he had more to say. MoMA gives him every opportunity, turning over one of its largest exhibition spaces to his work, with Althoff himself as curator. Art lies everywhere, seemingly at random, much of it piled together or still under wraps. Partitions have fallen away, in favor of whatever divisions might emerge from the artist's tables, easels, and pallets. A coarse wood floor, painted white but well scuffed even before public access, covers the usual one, as if to protect him from himself. Consider it a wise idea.

The two hundred objects look as casually assembled as they are arranged. Figurines have the clumsy air of a child's modeling clay. Paintings approach Paul Gauguin on Quaaludes, German Expressionism without the sharp edges, or simply amateur night. A rug remains half curled up and a balloon heart stuck in an air vent. Antique dolls lie apart from their beds. Discarded furniture, used fabrics, and an entire model city in black fill the awkward spaces in between.

Is it a yard sale, a thrift store, a warehouse, or a studio? Is it a retrospective or an installation? For Althoff, they amount to much the same thing. MoMA's Laura Hoptman turns over the press release to an actual artist's statement, but its rambling paragraphs boil down to little more than this: "I cannot choose, but I must." The show's title, "and then leave me to the common swifts" (repeated in German) seems to catch him in mid-thought, but a thought that never quite makes sense.

You may not find a puzzle worth teasing out. Some themes do emerge, though, just as the show's scale attests to bold aspirations—and just as its execution attests to futility. Paintings and photographs show friends hanging out for a lifetime or just for the day. The tormented dolls hint at an unhappy childhood, and the show claims to span much of Althoff's fifty years, although most of it dates from just a few years around the turn of this century. Perhaps he became a celebrity artist only to run out of ideas. Perhaps he had few ideas all along.

Critics have read a great deal into his work. They have seen inventive installations and a haunting sadness. They have seen memories of Hasidic culture or a bridge between New York and his native Cologne, where he splits his time. Maybe, but one can read practically anything into all this and still lack for meaning. Althoff emerged in the infuriating wave of overblown installations, with some of the biggest. A collaboration with Nick Z., the street artist, only confirmed their macho and their glibness. He later brought his depictions of claustrophobia and high society to the 2012 Whitney Biennial.

Althoff's collecting may recall the legendary 1978 show of "bad painting" at the New Museum, curated by Marcia Tucker. Yet Tucker was aiming another blow against late Modernism, and those days are past. He may recall the provocation of "thrift store art" from Jim Shaw, but Shaw hung anonymous paintings on gallery and museum walls. Althoff has little interest in breaking the boundaries between insider and outsider art, and he has little space for anyone but himself. It will take others to make a statement beyond the artist as brand name. It will take others, too, to stop trashing the gallery and to start poring over the trash.

"Take Me (I'm Yours)" ran at the Jewish Museum through February 5, 2017, Kai Althoff at The Museum of Modern Art through January 22. Hans-Peter Feldman ran at 303 gallery through October 29, 2016.