The Lay of the Land

John Haberin New York City

Sarah Morris and Elliott Green

Ian Cheng and Maureen Gallace

For Sarah Morris and Elliott Green, the landscape keeps slipping away. Both work close to abstraction, and both make it difficult to know just what they are painting.

That difficulty could well be their real subject, but in very different ways. Morris wants one to see her patterns as anything but pure color, while Green embraces abstraction and landscape alike. Morris sees herself as painting actual cities within global networks, while Green sees the earth apart from urban structures and human means of control. Meanwhile Ian Cheng works with video games and Maureen Gallace in landscape painting, based on unstated myths and divisions within America.  Does that make art a political act, or is meaning in the eye of the beholder? Color itself may hold out hope for painting, video, and the earth.

Does that make art a political act, or is meaning in the eye of the beholder? Color itself may hold out hope for painting, video, and the earth.

Breaking the code

Sarah Morris has some of the liveliest abstract art going. Only one problem: it means something. Those bright, glossy colors rippling across the surface? They represent, she promises, "codes, systems of control, and power structures that characterize urban, social, and bureaucratic typologies." Oh, right, I should have known.

But I did not, and is that really a problem? Not necessarily, not if you believe that a painting should speak for itself. You can then accuse her message of pretension and irrelevancy, but still allow the paintings to speak. The jagged color fields, their avoidance of easy primaries, and their love of black accord with a revival of geometric abstraction, with such artists as Gary Petersen and Don Voisine. Smaller works reduce to thin diagonals, while earlier series build on arcs and circles, in rows that rarely come to completion. They could be deconstructing Damien Hirst, just when he and his audience are souring at last on his mass-produced dots.

Even there, though, they refuse to stand apart from critical theory. They see painting itself, like Hirst's, as wrapped up in shared codes and global markets, and they care more about the failure of markets than of paintings. They become, as the show's title has it, "Finite and Infinite Games," with the players keeping their hands close to their chests. It is only a short step to see them as diagrams of cities that Morris has visited, studied, and filmed—most recently, Abu Dhabi. An earlier film saw choreographed movements in both athletes and political leaders at the Beijing Olympics. For her, mass entertainment helps sustain political and financial empires.

She has an obvious precedent in an older code breaker, Peter Halley, who refuses to believe in the primacy and purity of self-expression. They have even exhibited together in what the Guggenheim called "The Shapes of Space." Halley's Cellblocks look abstract, too, and use commercial Rolotex, much as Morris sticks to house paint. He riffs on memories of a prison in the Spanish Civil War, in paintings by Robert Motherwell, but for a later and more domestic system of control. Unlike Motherwell, too, he has no sense of those memories as incidental to Abstract Expressionism on the one hand—or discernible without a cheat sheet on the other. Morris just happens to make code breaking a lot harder and a more overtly political act.

Still, Halley thrived when Postmodernism all but demanded an end to painting. Does it still work when the subject of critique mostly shifts from painting to politics? Is there a serious disconnect if one, like me, can walk through an entire show seeing only jagged colors—and still, for that matter, cannot make head or tail of their structures and typologies? When Morris paints on film posters for Dune and Exodus, is she continuing her assault on spectacle and tales of freedom, and how would one know? Does it help that older art, such as the Renaissance, depends on shared understandings, too, for its religious significance and the "truth in painting"? Allow me for now to have my doubts and then some, to look forward to learning more, and to indulge for now in the colors.

If these paintings serve as choreography for a highly constrained dance, Jorinde Vogt treats works on paper as musical scores for a collaborative performance. Song of the Earth, its title after Gustave Mahler, fills a long wall with drawing, painting, gold leaf, and text. It also serves once during its run as the backdrop to music by Claire Chase and Pauchi Sasaki. Vogt's previous work incorporates curves and donuts out of a physics class in electricity and magnetism, and here the bright, pale shapes look like portions of continents drifting across the sky. Does it matter that I could not read, much less interpret, her all but indecipherable scrawls—no more than the codes for Morris? Maybe, but they are anything but systems of control.

Climate and color

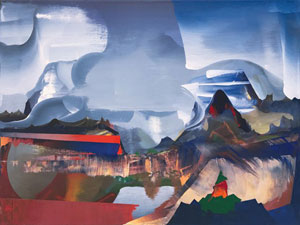

Global warming may not bode well for the planet, but it holds out hope for a few—those with an eye for color. Picture mountainous arctic ice giving way to cracks, fragments, and open seas. Picture coastal cities in all their glory as cryptic still points amid flowing water. Picture farmlands and flood plains with the colors and patterns of parched earth. It could upset familiar distinctions between foreground and background, structure and atmosphere, or formal sweep and close detail. It could give landscape painters one more excuse to do without people, but for Elliott Green it is just "Human Nature."

Already it does not take an active imagination so much as a steady eye—as in the opening room for climate data and sea-level rise in "Perpetual Revolution" at the International Center of Photography. Plenty of others, too, are working between representation and abstraction, with a little help from Postmodernism and the planet. Katharina Grosse has filled an upscale gallery with her color stains, flaunting her status as a painter, but the summer before she drenched a hut on Jamaica Beach, one already ruined by Hurricane Sandy, with poured red. I cannot swear that Green has climate change in mind at that, but it comes to mind with titles like Cold Meets Hot or Beach Mountain. It also comes to mind with his layered, fluid compositions. Here sky really does meet sea.

Green runs to natural colors for unnatural events. Deep greens, blues, reds, and tans identify broad areas with grass, ocean, sunlight, and dirt. They also help keep a large canvas in order, even as everything is in motion. Textured curves like waves dominate, but not to exclude rising color fields and mists. At a glance, they may look like poured paint, but their thickness and opacity bring a fragmentation akin to Cubism. Every so often, cities do appear, mostly dwarfed and in the distance.

A few canvases go all the way to abstraction, once in color as Fist and Shadow, not in the show. Others do so on a modest scale in black and white, with repeated curves that Tara Donovan or David Reed might call their own. They suggest that Green's real subject is painting and change, as does a title like Polyvalence. They may also suggest a location within the mind, as with North of the Hippocampus. In a time of climate change and tree loss with its human costs, what some call the Anthropocene and what Asia Society depicts as "Coal + Ice," it gets harder and harder to distinguish the human and nature. Given creativity and art, that might not be the end of the world.

Still, things do look apocalyptic. One can hear the dangers in titles like Fire Drip, Photon Skirt, and Bone Dust Beach. One can hear a long time scale in Mineral Ancestors, and Green takes obvious pleasure in his titles. He also looks back to the last time that truth to nature bordered on abstraction and the end of the world. Swirling colors appeared, too, in the Romanticism of J. M. W. Turner and the Hudson River School. In this vision of the future, the sublime is now.

Green differs, though, in not painting anything particular. He also has fatter mists and harder edges, because he is painting change as much as the scene at hand. The shards have the appeal of bright color for its own sake. Darker colors often reinforce a crest, while also calling attention to the sudden leaps in depth. The elements, they imply, have been around for a while, even if they are moving fast. If they start to look like grandstanding, that, too, is human nature.

Emissaries to a common culture

Ian Cheng and Maureen Gallace invite you on a journey through time and space. Cheng's animations and Gallace's paintings unfold in unfamiliar landscapes and disturbing times, or so they would like you to know. His Emissaries took him just three years but covers untold millennia and the course of civilizations. "Clear Day" took her twenty-five years in search of "our common culture" and New England. Robert Frank and The Americans have nothing on this project. Yet the real shocker is how little is going on.

Cheng's leisurely pace is all the more surprising since he worked in a platform for the design of video games. He is also streaming the trilogy on Twitch, known for games that test a player's reaction times, successively over the course of the exhibition. It plays out simultaneously at MoMA PS1 as well. The LA artist has worked with Paul Chan and Pierre Huyghe, and he signals the work's importance by its sheer size, with projections up to ten feet tall—two of them roughly as wide as The Last Supper. He signals it, too, with such evidently profound titles as In the Squat of Gods, At Perfection, and Sunsets the Self. If that sounds in need of translation from the original artspeak, they also come with enough wall text to occupy civilization for a long time to come.

Cheng's leisurely pace is all the more surprising since he worked in a platform for the design of video games. He is also streaming the trilogy on Twitch, known for games that test a player's reaction times, successively over the course of the exhibition. It plays out simultaneously at MoMA PS1 as well. The LA artist has worked with Paul Chan and Pierre Huyghe, and he signals the work's importance by its sheer size, with projections up to ten feet tall—two of them roughly as wide as The Last Supper. He signals it, too, with such evidently profound titles as In the Squat of Gods, At Perfection, and Sunsets the Self. If that sounds in need of translation from the original artspeak, they also come with enough wall text to occupy civilization for a long time to come.

They have something to do with the very idea of "cognitive evolution" in the face of "social and ecological forces." In the first, life on the edge of a volcano suffers from brutal conquests while a duly cute heroine finds her way. In the second, the active volcano has given way to a more comforting crater lake, but the living destroy one another anyway. In the last, the life force has become oceanic, but not enough to stop further collapse. They involve leaders by the name of AI and Mother AI, presumably not the three-toed sloth native to South America and crossword puzzles. Artificial intelligence never quite lives up to its name in the present century either.

For all that, the look is welcoming and progress is glacial. People wiggle, fires burn, and something much like an uprooted shed or tree tumbles closer to earth. Birds fly past and dogs wander in, but no one seems to be going anywhere special. Snow-capped lands give way to gentle contrasts and warm colors. Cheng's true gift may lie in creating a space for contemplation—more like Doug Wheeler and his Synthetic Desert than anime. Let me know when the emissaries arrive.

Gallace has a lot on her mind as well. She speaks of genre painting, although it looks nothing like the Mississippi for George Caleb Bingham in the nineteenth century. She speaks, too, of disturbances and disconnections in rural America—and a reflection of everything from a divided nation to the economics of home ownership and powerful financial institutions. In reality, she keeps returning to familiar territory, like Lois Dodd, in the Connecticut suburbs and on Cape Cod, and nothing much seems to change over the years. A grouping by subject only heightens the similarities. The creamy textures, spare colors, bare geometries for shelters, and looser brushwork for vegetation are reasonably skilled but thoroughly conventional.

They stick to the daylight brightness of summer and snow, from shorelines and beach houses to barns and suburban homes. True, Gallace bars access, with no people, no clear roadways, and a near absence of doors or windows—but that simplification is common enough in Modernism or realism today. I could see it again recently with Sweden for Rita Lundqvist or with gallery exteriors haunted by pillars of light for Adam Gordon, at Chapter NY through April 23. Gallace's most evocative landscape may well be MoMA PS1. More than fifty panels as small as notebook paper spread out across eight rooms, ceding space to the surrounding white walls. When it comes to the politics of art and real estate, only starting with MoMA's expansion, "too big to fail" has nothing on the museum.

Sarah Morris ran at Petzel through April 8, 2017, Jorinde Vogt at David Nolan through March 25, Elliott Green at Pierogi through March 26, and Ian Cheng and Maureen Gallace at MoMA PS1 through September 12.