Less than Zero

John Haberin New York City

Group Zero and Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian

So many movements. So little time.

With "Zero: Countdown to Tomorrow," the Guggenheim demands attention for yet another, but others may lose count. From its beginnings at the Düsseldorf Art Academy in 1957, Group Zero did not so much innovate as play well with others, including some of biggest names in European painting and sculpture. It was both more and, I am afraid, less than zero.

Was disco the death of rock and roll? To judge by Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, it did in a decade's worth of art as well. She has dedicated a lifetime to a Minimalism in mirrored glass, drawing on Islamic art, mathematics, Minimalism, and the dance floor. Group Zero would fit right in.

A movement in motion

Maybe you grew tired of art movements long ago. Maybe you grew tired of sorting them out. Maybe you never heard of half of them, when art could still aim for the diversity and urgency of Modernism. From around 1960 alone, there were Arte Povera, Giuseppe Penone, and Marisa Merz in Italy, Gutai in Japan, Nul in the Netherlands, Nouveau Réalisme in France, G58 and COBRA in Belgium, political art like Aktual and OHO further east, and Fluxus everywhere. Maybe you wish that people could forget the whole thing and just get on with making art. Start again at zero.

Only guess what: that, too, was a movement. Heinz Mack and Otto Piene met in art school and declared themselves Group Zero, after the countdown of space shots and the nuclear age. The third issue of their magazine, with a cover by Mack, displayed an actual blast-off. Günther Uecker fell in with them almost from the first and formally joined in 1961. They insisted on the priority of experiment in painting, print, and performance, with new materials, periodicals, "street action," and light shows.

If that sounds less like amazement in art and more like a day in the life of the 1960s, so is their retrospective. With nearly two hundred objects, it becomes an exercise in obscurity and nostalgia, but also a handy look at goings-on in and out of Europe. It draws on artists from every one of those often forgettable movements and from Japan to Latin America. They all joined in rebellion against the painterly excess of Tachisme in Paris and Abstract Expressionist New York, much like America's Pop Art and Minimalism. While its big three supply about half the art, following a more modest summer show at the Neuberger Museum in Purchase, others provide the big names and the innovations. The curators, Valerie Hillings with Edouard Derom, speak not of a movement but a "network."

A burgeoning art market puts a premium on discoveries and rediscoveries, and so do museums. They have displayed forgotten Minimalists and global Minimalisms—including Lee Ufan and Mono-ha in Asia, Lygia Clark and Neo-Concretism in Latin America, and Gutai. Careers may depend on it. Only recently, the Guggenheim argued for extending another movement, Futurism, by decades. The 1960s, though, may offer particular opportunities for a fresh look. Globalization really was underway, and the space between Minimalism and Post-Minimalism can get one questioning the divide between formalism and body art or conceptualism and physical sensation.

Every one of them is at play in the High Gallery off the first ramp, where the Guggenheim restages the group's first big exhibition. And already Zero's priority is in question—or its very existence. "Vision in Motion–Motion in Vision" took place in 1959 not in Germany but Antwerp, and its contributors are all over the map. Mack is moving toward reflective materials in motion in resin and cloth, but Jesús Rafael Soto from Venezuela has his own "vibrations" in paint. Piene is inching away from flatness in monochrome, but Pol Bury from Belgium has a grid of cuts in his slowly rotating black disk. Uecker will be making his reputation with nails protruding from canvas and sculpture, but Dieter Roth is already cutting across space with twine wrapped around an open circle.

Others are more aggressively pursuing new media and motion, starting with words. Daniel Spoerri spools text from a machine not unlike a loom, while Robert Breer's film shows font samples slowly sinking away. The tightly clustered display could easily pass for the work of a single artist obsessed with creaky constructions, but its diversity is hard to miss as well. For one thing, each artist's last name appears as back in Antwerp, in big block letters on the floor below the work. For another, Zero has not yet had its first birthday, and already it said what it had to say. The rest of the show runs thematically, because its ideas were pretty much in place.

When art was happening

The first ramp has new conceptions of painting, centering on Piene, mostly monochrome muted and roughened by brushwork and sand. Next come silvery vibrations, notably Mack's, with or without a motor to twist slowly in the wind. Then comes the creative destruction of burning, cutting, and nailing, with Piene's Venus of Willendorf in soot and Uecker's nails—blossoming into a monumental white bird. Finally come the themes of light, nature, and space, from light shows to land art. Piene has a room for his Light Ballet, while Mack creates his own environment for photos of the Sahara, with light boxes. The exhibition concludes with Lichtraum, or "light room," a group exhibition of reflective surfaces and moving parts.

But wait: surely you have seen all this before, with other names attached. Monochrome dust may have you thinking of Yves Klein with his blue sponge and carpet of blue pigment, trademarked as "Klein blue," or Piero Manzoni painting with cobalt chloride. Burning goes back to Klein's Fire Paintings with a blowtorch and Manzoni with his own soot. Lucio Fontana and Alberto Burri did their share of slashing, with near parallel cuts in rectangular fields, charred wood and plastic, and bronze spheres seemingly erupting from within. George Rickey, an American then in Berlin, and Jean Tinguely drove kinetic art. Arman had his reflective surfaces of candy wrappers, Manzoni his balloon Body of Air, Fontana his Concetto Spaziale, and Yayoi Kusama no end of dark rooms with flashing lights.

All these appear, but then Klein staged a performance on opening night in Antwerp. That light room was billed as an homage to Fontana, and Fontana in turn contributed a catalog design. One can have fun, too, with Gianni Colombo's pulsating Styrofoam bricks, Christian Megert's mirror shards, Armando's iron bolts and barbed wire, Dadamaino white ovals, Bernard Aubertin's Fire Book of burned matches on aluminum and wood. At the press preview, one of the Zero artists blew on a mobile by Rickey, to show how it moved. Jan Henderikse's wall of beer bottles looks like a wine cellar for blue-collar types. Still, while the artists continued to work, the movement all but burned itself out by 1964.

It feels caught up in the 1960s all the same. When Piene described Zero as a "zone of silence," I could think only of Maxwell Smart and his cone of silence. As reflective spheres rotate in the near darkness of a dance floor, I could almost name the dance. The Guggenheim deserves part of the blame for the tameness. Three floors of Mack at his gallery shows more of his sparkle right up to today. He could fill an entire wall in paint, reflective tape, or aluminum. His light boxes could aspire to Surrealism, with otherworldly shapes towering over the sand.

Even the museum recreations have a way of embalming them. That first room lies off-limits to visitors, like a display in a museum of anthropology or natural history. The lights in that final room are on a timer, and the objects look all the more inert in the dark. Still, Zero must share the blame as well. The show obliges one to compare it to its collaborators and influences. It comes off as at once too unfocused and too controlling.

The early abstractions prefer dull colors and lumpy surfaces to Fontana's slash and Klein's burn. The kinetic art never goes so far as to self-destruct like Tinguely's Homage to New York. Compared to Walter de Maria or Robert Smithson, Mack in earthworks refuses to get his hands dirty. The parallel traces in his Sahara seem in denial of Smithson's beloved entropy. Well before the end, Zero comes off as a quaint and all too masculine echo of the summer of love without the free spirit. This happening refuses to happen.

Disco Minimalism

But seriously, who killed Minimalism? Was it the Neo-Expressionism of Georg Baselitz and Julian Schnabel in the 1970s, with its outsize gestures, outsize narratives, and equally outsize egos? Was it the "Pictures generation" of Sherrie Levine and David Salle soon after, with their critique of the avant-garde? If that sounds like way too much "theory," go ahead and blame disco—the flash, the trash, and of course the disco ball.  Who could look at a mirrored sphere and think of geometric abstraction the same way again? Maybe it is just a coincidence, but Piotr Uklanski, who has turned a gallery into a dance floor, also appeared in a show about Nazi Germany called "Mirroring Evil."

Who could look at a mirrored sphere and think of geometric abstraction the same way again? Maybe it is just a coincidence, but Piotr Uklanski, who has turned a gallery into a dance floor, also appeared in a show about Nazi Germany called "Mirroring Evil."

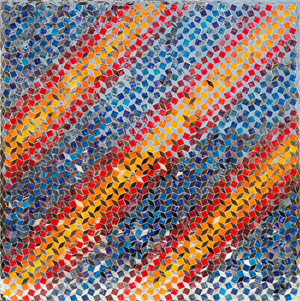

Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian was there before him, but she insists that Minimalism lives on, give or take the glitz. At the Guggenheim, small but shining spheres rest together on a podium, shorn of the hustle and the night. They help kick off "Infinite Possibility," a retrospective. It is only the latest in a headlong rush of attention to global Minimalisms, in the plural—including Group Zero. Farmanfarmaian, too, roots Minimalism's spareness and repetition in local culture and tradition. She sees her work as an extension at once of the club scene and a mosque.

Born in 1924 in Iran, she has every right to claim a dual focus on East and West. Like Lee Krasner, she studied at the Art Students League in New York, and she hung out with the New York School. When she sets a felt-tip pen and ink to paper, in small dabs that progressively fill a sheet with color, she builds on Islamic calligraphy and carved wood screens as well. Their curves recall the margins of medieval texts, but also Frank Stella with his "Protractors" and "Exotic Birds." Again like Frank Stella, Farmanfarmaian can also claim a focus on both structure in space and decorative arts in the plane. She has worked as an architect and created fashion layouts for Bonwit Teller.

For all that, she felt her greatest influences from half the planet away. As curators, Suzanne Cotter, director of the Serralves Foundation in Portugal, and the Guggenheim's Karole Vail make a point of her traditionalism. Yet she left home in the shadow of World War II and passed her formative years in America. She fled Iran again with the fall of the shah, well after Siah Armajani, returning only in 2003. As for Minimalism and the club scene, she spent the intervening 1957 to 1979 in Tehran. Somehow, wherever she went, she was in exile. She may have felt the impersonality of late Modernism as the story of her life.

For all that, her Iranian Modernism and Iranian contemporary art boils down to simple gestures and still simpler pleasures, multiplied over and over again. The show leaps from the 1970s to just the last few years, but Farmanfarmaian is still pushing the same ideas to their logical but glittery conclusion. The first section has straightforward glass constructions, along with the drawings. Silvered strips alternate from horizontal to vertical as she moves from square to square in a grid. Other constructions introduce drawing in space, like three triangles with a shared base—the outer two pointing up and other pointing down. She might have made them in a single stroke zigging up, down, up, down, and back across to where she began.

Her most recent work looks back to the roots of mathematics in both Islamic art and the West. She assembles glass triangles into symmetric, pockmarked polygons in series. One set spirals upward from the floor, while their outlines run from a triangle to a decagon. Nested squares on a rotating platform create a spiraling pyramid in motion. At last the disco ball is spinning, although a little too large and a little too late. Farmanfarmaian's interests outstrip her sometimes embarrassing results, but she is still a reminder of why Minimalism refused to die.

"Zero: Countdown to Tomorrow" ran at The Guggenheim R. Guggenheim Museum through January 7, 2015, Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian through June 3l. Heinz Mack ran at Sperone Westwater through December 13, 2014.