Made in Japan

John Haberin New York City

Tokyo, Gutai, and a New Avant-Garde?

"Tokyo: A New Avant-Garde" promises a great deal, just when art seems no longer capable of delivering—the new and the avant-garde. Yet in fact the Museum of Modern Art is far too modest. Strange and intriguing names fly by faster than even a New Yorker can take them in.

More to the point, these are avant-gardes, in the plural, in a quarter century of movements and collectives. And to believe the Guggenheim, one movement in "Gutai: Splendid Playground" spanned almost them all.

Avant-garde from the ruins

They may be newer still depending on your expectations. If you had not heard much about a Japanese avant-garde, from 1955 to 1970, you might wonder if it could ever have existed. Tradition, nearly a century of militarism and empire, and briefly a state religion, leaving tens of thousands dead, cities in ruins, western occupation, and the new conformity of Asian capitalism—any or all of this might easily preclude art. "Made in Japan" back then did not exactly promise much either. And the show begins the very year of Sony's first portable transistor radio, although that device was and is still a marvel. It ends the year that the Red Army Faction hijacked a plane to Korea.

Only none of those stereotypes applies. The exhibition looks at first like a compact survey of Western art from much the same years, from Surrealism and abstraction to Pop Art, performance, and Minimalism. Or rather, it looks like a war-torn nation struggling to understand its crises and transformations through Western art—and, in turn, Western art through its own crises and transformations. By 1970 Japan was the third leading economic power and Tokyo the world's most populous city. Yoko Ono (with her Cut Piece) and Nam June Paik had performed there, but so had Frank Sinatra, My Fair Lady, and the Beatles. The show poses questions about the impact and limits of an increasingly global culture.

Besides Ono and Paik, one will have heard, no doubt, of On Kawara and Yayoi Kusama. Before his date paintings, Kawara made what looks like conventional abstraction, give or take the automobile tires on shattered paving stones. Long before her fashion shoots, Kusama was her decorative self on canvas. Gutai, a counterpart of Abstract Expressionism in the 1950s and an influence on Fluxus, follows at the Guggenheim, after a superb introduction to the group at Hauser & Wirth. In just the last year or so, Lee Ufan and Mono-ha have had exhibitions, as well as Nasreen Mohamedi in India, introducing their version of Minimalism. It took me those two shots at Japan in the 1960s to get over its strangeness, to see not just gimmicks but the meeting of objects, conceptual art, and contemplation.

That list omits plenty of less-familiar artists, but it serves as a decent outline all by itself. The entire show cannot deliver all that much more, faced with a quarter century. Think of it as an extended time line and tutorial for those wondering by now how it all fits together. So much recent attention, too, says something about the art scene. Markets and museums are responding to globalization, the search for new hot tickets, and postmodern skepticism about an official history centered on Abstract Expressionist New York. Think of the Guggenheim's summer survey of abstraction, which shifted the focus to Europe, or the ubiquity of Manga right now.

Manga, which had its roots back then, is not much in evidence (thankfully), but everything else sure is. Even a skeptic when it comes to Japanese art and netsuke has a point, though: "Tokyo" starts ten years after World War II, when art had some catching up to do. First it had to move past a strict documentary impulse. And its first recourse is a backward glance at tradition and Surrealism, as metaphors for devastation and rebuilding. Okamoto Tarō photographs earthenware, but with the look of rugged abstract sculpture, and paints Law of the Jungle with a zipper running down the middle. Nakamura Hiroshi offers War, Peace, and Upheaval, but they seem all one.

Ten years later, that artist still stuffs as much as he can into hard-edged paintings of conformity and danger. One-eyed girls in uniform line a subway (or maybe one of those new bullet trains), with a storm at the center. And the obvious irony has a cartoon side from the very start. Ay-O's Pastoral depicts row upon row of pink humanoids in robotic lockstep. Maybe a hint of popular culture helps art adapt to the postwar world. Still, Ay-O was to join Fluxus, and it took experimental movements like that one to get past the acrobatics of violence.

Between propaganda and today

Jikken Kōbō (Experimental Workshop), for one, still insists on the art object. This group includes Yamaguchi Katsuhiro's glass vitrines that change color as one moves, his slide show of hands as one of the first sound pieces, and Kitadai Shōzō's debts to Alexander Calder and Constructivism. Hi Red Center places objects at the center of performance art. It designed its Shelter Plan, including a stained and bound suitcase, for Frank Lloyd Wright and the Imperial Hotel. Among its artists, Akasegawa Genpei managed to get himself arrested for a collage of counterfeit 1,000 yen notes. In Japan, it seems, the roots of Pop Art are in subterfuge and subversion.

That definitely does not preclude overstatement. Kojima Nobuaki drapes the stars and stripes over a polyester man in shirt and tie, as if America had imposed a dress code while eliminating his head. Kikuhata Mokuma covers pillars and an altar with satin and coins. In case one missed the point, Tetsumi Kudō titles a sculpture of socks Philosophy of Impotence. The 1960s brought greater freedom, but also still greater garishness—like his baby carriage that opens to a "cocoon" of red paint and flashing lights. If you spot the influence of combine painting, Robert Rauschenberg visited Tokyo, too, and Ushio Sinohara simply copied his winged Coca-Cola bottle.

The torrent of movements had its more patient side. Group Ongaku (Group Music) and Shiomi Mieko riff on sheet music. But then John Cage, David Tudor, and Merce Cunningham performed in Japan as well. Among the founders of Hi Red Center, Takamatsu Jirō draws a sumptuous curve in black string, punctuated only by tying it into nodes. Nakanishi Natsuyuki also connects minimal means to bodily sensation, with pins stuck in canvas—or a rearview mirror deflected into a kind of makeshift Constantin Brancusi. And then come Gutai and Mono-ha.

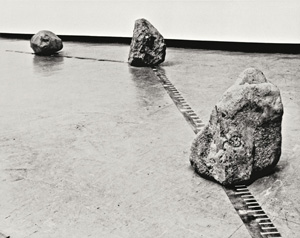

Critics often compare Gutai to another overseas take on abstraction and action painting, Tachisme in France, but its parallels and processes range more widely. Murakami Saburō lets a painting take shape by throwing a ball across it, much as John Baldessari photographed a line of balls in the air, and tears six holes in brown paper, much like the slashed canvases of Lucio Fontana or Alberto Burri. Shiraga Kazuo describes an impasto of red and black oils as Mud Wrestling, and that is exactly how it came about. Mono-ha worries much less about wrestling with painting. Narita Katsuhiko creates a rock garden out of charcoal. Ufan does much the same with actual stones on the measuring tape that marks their placement.

Critics often compare Gutai to another overseas take on abstraction and action painting, Tachisme in France, but its parallels and processes range more widely. Murakami Saburō lets a painting take shape by throwing a ball across it, much as John Baldessari photographed a line of balls in the air, and tears six holes in brown paper, much like the slashed canvases of Lucio Fontana or Alberto Burri. Shiraga Kazuo describes an impasto of red and black oils as Mud Wrestling, and that is exactly how it came about. Mono-ha worries much less about wrestling with painting. Narita Katsuhiko creates a rock garden out of charcoal. Ufan does much the same with actual stones on the measuring tape that marks their placement.

Go Hirasawa of Meiji-Gakuin University, Roland Domenig of the University of Vienna, and MoMA's Joshua Siegel do include architecture, photography, and graphic design, such as Yūsaku Kamekura's poster for the Olympics. They hint at the eager-to-please illustration in Asian art now. Together in the last room, though, these media look more like documentation. Some of the best photographers indeed work in a style between documentary and theater, like Moriyama Daidō and Tōmatsu Shōmei. By this time, one is working hard anyway to take it all in. One contrast to New York in those same years is a priority of practice over theory, and that can leave anyone at a loss for words.

So is there a distinctly Japanese avant-garde—or a "third mind" between East and West? Compared to the west, would it be more inner directed or more political? Did the patience of Ono, Paik, and Shigeko Kubota bring Fluxus to Japan or Japanese tradition to New York? Maybe all of the above. And even a single avant-garde is always in the plural. I would give the last word to a poster by Yokoo Tadanori, Between Propaganda and Today.

Late to the party?

Gutai came late to the party, but what a party! That could describe the entire course of postwar Japanese art, in a nation with deeper shocks on its mind than Modernism. It could have left a stale, tepid rehash of Abstract Expressionism. (Remember the scathing tone with which critics once pronounced Joan Mitchell or Helen Frankenthaler "second generation"?) It could have meant a subtle revisioning of Western art through eastern eyes, much as the Guggenheim in 2009 pronounced a view in the opposite direction "The Third Mind." It could have imbued abstraction's splashes, drips, and tears with echoes of devastation and rebuilding.

Now the Guggenheim finds all three, but something else as well. The Gutai Art Association, founded in a town near Osaka in 1954, had the advantage of its distance from both Tokyo and the west. It could start relatively fresh—fresh enough to see one change after another in Western art and to relish the turmoil. Its collective activities parallel not just painting, but Fluxus, Black Mountain, Yves Klein, and the happenings of the 1960s still to come. In this mad scramble of places, times, and movements, one spends most of the show in the 1950s while "Somebody to Love" plays from across the ramp. Gutai came late, but it partied like there was no tomorrow.

To be sure, the group started with Jackson Pollock. Its publication featured Pollock's spread in Life magazine, and it invited Life to come document it as well. When the founder, Yoshihara Jirō, set out a chalkboard with the invitation to "draw freely," he was collectivizing Abstract Expressionism. And visitors have responded by spilling color onto the wooden frame and support. Jirō bows to tradition, too, as with a calligraphic black painting broken by a white impasto circle. It is hard not also to think of destruction after a bomb.

Gutai's manifestos, though, have almost no trace of deference, tradition, or darkness. They speak to "today's consciousness" and "a new autonomous space for pure creativity." Some projects reached out to children. "Gutai: Splendid Playground" invites one to step inside Yamazaki Tsuruko's red vinyl cube from its outdoor exhibition of 1955. It uses video to track the making of art right down to The Drama of Man and Matter in 1970. One can hardly complain if the museum's crowds and their cell phones ruin the contemplative and collective spirit.

Maybe one has to ruin the spirit in order to appreciate it. The installation runs chronologically, while each floor has a nominal theme such as "play" and "performance." Yet something serious underlies the glib optimism and helps connect the movement's competing versions of Eastern and Western art. Its name means concreteness, and it spoke from the beginning of not separating spirit and matter. Where conceptual art often leaves a physical or documentary record, it can make a point instead of its own vanishing, like the invitation from Yoko to cut away her dress. Although Mukai Shūji burned all his work in 1961, Shiraga Kazuo's mud wrestling left a work of art.

So did Yoshida Toshio's burns in a panel, Tanak Atsuko's sand drawing, Montonaga Sadamasa's nails coming out of a pillar, Shiraga Fukiko's bullet holes, Uemae Chiyū's glue and sawdust, Shimamoto Shōzō's hurled bottles of paint, or Murikami Saburō's passing right through the canvas—and the leftover unsettles the closure of a performance just as deconstruction would predict. The colors and compositions can seem as heavy as any second generation's, much like, again, Tachisme in France and Arte Povera in Italy—but then the first does derive from a word for stain, and the latter tore apart the work of art. By the end, the movement left more shiny objects and bright lights, looking quainter and quainter on successive visits, but it partied hardest long before psychedelia. The Guggenheim gives more weight than expected to the performance, while Hauser & Wirth recently gave more weight to polished works of art. That makes sense, given the priorities of museum revisionism and gallery sales, but one needs them both. For Gutai, the spirit requires a concrete remainder.

"Tokyo, 1955–1970: A New Avant-Garde" ran at The Museum of Modern Art through February 25, 2013, "Gutai: Splendid Playground" at The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum through May 8. "A Visual Essay on Gutai" ran at Hauser & Wirth through October 27, 2012. Related reviews look at Yayoi Kusama, Lee Ufan, and "The Art of Mono-Ha."