6.28.24 — Dressing the Part

Sonia Delaunay liked to say that she lived her art. At the very least, she dressed the part. She was not the only modernist with an urge to experiment and a grounding in design and everyday life. She did, though, know how to live.

One first encounters her at Bard College Graduate Center, or at least a mannequin in her place, through July 7, already dressed for art. Not in studio clothes, although the show’s final floor has all the informality of an artist’s studio, with an invitation to join in. Throw pillows set one at ease as the mess and dedication of an actual studio never could,  each covered with the artist’s rhythms and colors. And back downstairs, on film, she is at work herself, surrounded by the same patterns, in progress or on herself. More formally, in a full-length photo, a dancer wears a dress of her design as Cleopatra. Delaunay’s dedication to form extended to collaboration and across the arts.

each covered with the artist’s rhythms and colors. And back downstairs, on film, she is at work herself, surrounded by the same patterns, in progress or on herself. More formally, in a full-length photo, a dancer wears a dress of her design as Cleopatra. Delaunay’s dedication to form extended to collaboration and across the arts.

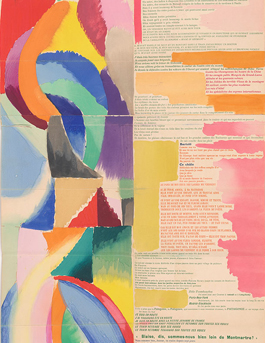

Born in 1885, she came upon her form with her husband, Robert Delaunay, and they never once departed from it ever after. You may know it from his paintings—their half circles spiraling down the canvas as if in motion. Assembled triangles or, if you like, disassembled diamonds lock the pattern in place, leaving no hint of a background color and nothing unpainted. They called it Simultané, which has entered English as Simultanism, and they felt it as not just a personal discovery, but one to be shared with humanity as the breakthrough between art and life. Colors run to pure primaries, but not to overwhelm the senses with their brightness. One remembers them equally for their richness and shallow depth.

Who made the discovery? One may as well ask who discovered abstract art. Was it them, Francis Picabia, or Hilma af Klint before them all? Maybe just say that they invented it simultaneously. In any event, Robert has gone down as the proper painter, Sonia as the one who applied his art to practical and impractical purposes, a simplification that has made her all too easy to overlook. Much the same charge long dogged Sophie Taeuber-Arp compared to her husband, Jan Arp—and Taeuber-Arp first had her collaborations, too, including puppet theater. Just two years ago, a MoMA retrospective corrected the record for her, and Bard is out to do the same for Sonia Delaunay.

Delaunay gets all four floors of an Upper West Side mansion, but it does not feel packed. It devotes the first floor to an introduction, including a huge time line, and the fourth to that studio. Besides, she thought less in terms of multiplying work than in dedication, with a single style and extended projects. One could just as well say, at the risk of cliché, that she lived for art. She worked with leading choreographers and theaters, including the Ballet Russe, and even designed playing cards. She had not sold out, but they did.

She had a revival at that, with new commissions in her seventies, as collaboration became newly respectable—even before today’s care to merge art and craft. Think of Robert Rauschenberg, also in dance. Of Jewish background, she found safety from the Nazis in the south of France, although her husband died in 1940. She moved in with, sure enough, Jan and Sophie Taeuber-Arp, and commissions kept coming. They allowed her to work on a larger scale than ever before, in mosaics, tapestry, and interior design. Her furniture looks block-like and uncomfortable, but it allowed others, too, to live her art. It also helped answer a remaining charge, that she had never been ambitious enough.

She was never as edgy as Pablo Picasso at the height of Cubism, in his own close approach to abstraction, or as wildly playful as Taeuber-Arp. Cleopatra looks no more or less than expected in her pose and profile. The closest she came to the pursuit of the modern came early on, in illustrating a poem by Blaise Cendrars, on fuller display last year at the Morgan Library. It took her further, too, from Paris to the Trans-Siberian Railroad. She may have lived her art, but she was not out to transform ordinary life. She was first and foremost a woman of the theater.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.