Art for Living and Living for Art

John Haberin New York City

Sonia Delaunay, Orphism, and Frederick Kiesler

Sonia Delaunay liked to say that she lived her art. At the very least, she dressed the part. She was not the only modernist with an urge to experiment and a grounding in design and everyday life. So, they thought, were the artists in Orphism, and so was Frederick Kiesler. She did, though, know how to live.

Art was in turmoil, so why not the Eiffel Tower? In the hands of Robert Delaunay, it barely touches the earth with its unforgettable steel frame. Is it rising into the sky or collapsing once and for all? When he paints it again in bright red, has it caught fire, figuratively or for real? How about all at once? So it is with "Harmony and Dissonance: Orphism in Paris" at the Guggenheim.

Art was in turmoil, so why not the Eiffel Tower? In the hands of Robert Delaunay, it barely touches the earth with its unforgettable steel frame. Is it rising into the sky or collapsing once and for all? When he paints it again in bright red, has it caught fire, figuratively or for real? How about all at once? So it is with "Harmony and Dissonance: Orphism in Paris" at the Guggenheim.

Cannot get up the energy to go to a museum? Kiesler would understand. He wanted his work to respond to body movements, posture, and sheer fatigue. He saw his architecture and design as creating and breaching "fields of energy exchange," even when you cannot. With his Mobile Home Library, you need not so much as reach for a book to read sitting down. The book would come to you.

Its bare white shelves at the Jewish Museum do not look all that relaxing. A museum-goer cannot enter their half closed circle, for fear of damage, even as they wheel around the room or in place. Still, Kiesler was an idealist, and he took seriously the idea of Modernism as a science—a search for truth in service to humanity. If he seems largely forgotten, that may show how much that dream has faded, but do not be too sure. As postmodern critics loved to ask, has Modernism failed? Perhaps, but this modernist outlasted many a movement.

Dressing the part

One first encounters Sonia Delaunay at Bard College Graduate Center, or at least a mannequin in her place, already dressed for art. Not in studio clothes, although the show's final floor has all the informality of an artist's studio, with an invitation to join in. Throw pillows set one at ease as the mess and dedication of an actual studio never could, each covered with the artist's rhythms and colors. And back downstairs, on film, she is at work herself, surrounded by the same patterns, in progress or on herself. More formally, in a full-length photo, a dancer wears a dress of her design as Cleopatra. Delaunay's dedication to form extended to collaboration and across the arts.

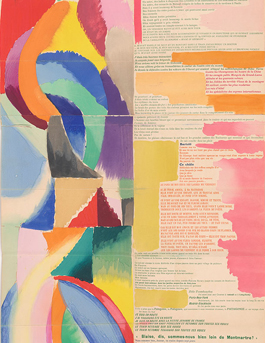

Born in 1885, she came upon her form with her husband, Robert Delaunay, and they never once departed from it ever after. You may know it from his paintings—their circles spiraling down the canvas as if in motion. Assembled triangles or, if you like, disassembled diamonds lock the pattern in place, leaving no hint of a background color and nothing unpainted. They called it Simultané, which has entered English as Simultanism, and they felt it as not just a personal discovery, but one to be shared with humanity as the breakthrough between art and life. Colors run to pure primaries, but not to overwhelm the senses with their brightness. One remembers them equally for their richness and shallow depth.

Who made the discovery? One may as well ask who discovered abstract art. Was it them, Francis Picabia, or Hilma af Klint before them all? Maybe just say that they invented it simultaneously. In any event, Robert has gone down as the proper painter, Sonia as the one who applied his art to practical and impractical purposes, a simplification that has made her all too easy to overlook. Much the same charge long dogged Sophie Taeuber-Arp compared to her husband, Jan Arp—and Taeuber-Arp had her collaborations, too, including puppet theater. A recent MoMA retrospective corrected the record for her, and Bard is out to do the same for Sonia Delaunay.

Delaunay gets all four floors of an Upper West Side mansion, but it does not feel packed. It devotes the first floor to an introduction, including a huge time line, and the fourth to that studio. Besides, she thought less in terms of multiplying work than in dedication, with a single style and extended projects. One could just as well say, at the risk of cliché, that she lived for art. She worked with leading choreographers and theaters, including the Ballet Russe, and even designed playing cards. She had not sold out, but they did.

She had a revival at that, with new commissions in her seventies, as collaboration became newly respectable—even before today's care to merge art and craft. Think of Robert Rauschenberg, also in dance. Of Jewish background, she found safety from the Nazis in the south of France, although her husband died in 1940. She moved in with, sure enough, Jan and Sophie Taeuber-Arp, and commissions kept coming. They allowed her to work on a larger scale than ever before, in mosaics, tapestry, and interior design. Her furniture looks block-like and uncomfortable, but it allowed others, too, to live her art. It also helped answer a remaining charge, that she had never been ambitious enough.

She was never as edgy as Pablo Picasso in his own close approach to abstraction, or as wildly playful as Taeuber-Arp. Cleopatra looks no more or less than expected in her pose and profile. The closest she came to the pursuit of the modern came early on, in illustrating a poem by Blaise Cendrars, on fuller display last year at the Morgan Library. It took her further, too, from Paris to the Trans-Siberian Railroad. She may have lived her art, but she was not out to transform ordinary life. She was first and foremost a woman of the theater.

Is Paris burning?

It was 1911, and Cubism had shattered convention with its assault on structure and representation. Picasso had not yet introduced rope into his illusory tabletops, marking the transition from Analytic to Synthetic Cubism. Already, though, one could speak of a choice at the very heart of modern art, between Cubism's line and, thanks to Henri Matisse, Fauvism's color. But why choose? Robert and Sonia Delaunay wanted both line and color, and they were not alone. The tall gallery off the Guggenheim's atrium has a startling display, from their rainbow colors to the deep blues of František Kupka and Picabia.

It was color in motion at that, like Kupka's closely packed curves of translucent whites, akin to stop-action photography years later. Marcel Duchamp dismembered a nude in much the same way, shocking New York at the 1913 Armory Show. Many an artist now at the Guggenheim exhibited there as well, including Albert Gleizes, more often remembered as a minor Cubist. Gleizes returned to New York during World War I after serving in the military. For Europe, the sense of turmoil was all too real. And still the School of Paris soldiered on.

But was it Orphism? Guillaume Apollinaire, the poet, coined the term, but history books have mostly settled on Delaunay's choice of Simultanism. The curators, Tracey Bashkoff and Vivien Greene, want something more poetic and encompassing than he could ever have produced. They include many outside Simultanism, like Gleizes and Duchamp. They see an international movement as well, from Natalia Goncharova in Russia to Morgan Russell and Stanton Macdonald-Wright in America—perhaps the first in modern art. Gleizes himself painted the Brooklyn Bridge with the same broken diagonals as Delaunay's tower. The turmoil had spread.

The shows sees the same exploration of motion in the tumbling bodies of Fernand Léger in Paris and Gino Severini in Italy—and the same approach to abstraction. In fact, Orphism got there first, before Vasily Kandinsky. It sees the same exploration of color in Paul Signac. Was Post-Impressionism more "scientific" than Orphism could ever be? Perhaps, but Signac had also painted a critic and dealer as a magician, pulling a flower out of his hat. This was turmoil, but it was still magic.

What, then, sets Orphism apart if everyone belongs? It was not just color or line in motion, but also a device to achieve it, circles. Sonia Delaunay has dozens of them, and Robert Delaunay changed the shape of his paintings to disks. They delighted in the globes of Paris street lights and in a Ferris wheel, only a stone's throw from the Eiffel Tower. For Marc Chagall, the Great Wheel gathers light within its circle like a nighttime sun. The parallel to color wheels in color theory (Kupka's Disks of Newton) must have been hard to miss.

Modernism has another pair of stories to tell besides line and color. For critics like Clement Greenberg, it meant an escape from clichés and conventions into a higher realm of art. For Postmodernism, it has meant instead putting a torch to fine art as distinct from life. It had to pass from Cubism to Dada—or, with Sonia Delaunay, from painting to fashion as a part of life. And here, too, Orphism refuses to choose. Art and its fire were in the air, like the Eiffel Tower and the Brooklyn Bridge.

Getting up the energy

At a given moment, Frederick Kiesler can seem merely quaint or way ahead of his time. Born in 1890 in the Ukraine, he seems just right for a world at war now. He headed off as fast as he could nonetheless—first to Germany, where he could see home design as both artifice and household necessity, and then to the Netherlands. He had success with stage sets, just as he later worked with performers at the Julliard. He did not join the Bauhaus, with its dream of art for the many, but he did accept an invitation from de Stijl, the movement with Piet Mondrian, before leaving for New York. He can seem the Forrest Gump of modern art, present at everyone else's creation, but he was more than a walk-on and never unwitting.

Where an artist as commercial as Andy Warhol saw his early work in fashion as a step toward something more, Kiesler anticipates today's growing interest in design as art. Nothing was above or beneath him. He undertook displays for Saks Fifth Avenue and a gallery for Peggy Guggenheim, Art of This Century in 1942. He worked with Film Guild Cinema starting in 1929. Does its name evoke both avant-garde film of the past and a revival house in the present? He taught for years at Columbia University, where he showed his students short films on everything from "radioactive rays" and "tiny water animals" seen under a microscope to "the world of paper."

He aspired, then, to art as a science, but also art of the everyday, and he could not separate the two. It led him to found the Laboratory for Design Correlation at Columbia in 1938. Mobile Home Library recalls prefabricated, affordable housing, but it incorporates mobility and vision as well. Architecture for him had to be light on its fight and had to design with light, well before lighting as art for James Turrell and Dan Flavin. Naturally his culminating projects were Vision Machines. Naturally, too, they drew on the science behind "how we see" in order to stimulate hallucinations and dreams.

He aspired, then, to art as a science, but also art of the everyday, and he could not separate the two. It led him to found the Laboratory for Design Correlation at Columbia in 1938. Mobile Home Library recalls prefabricated, affordable housing, but it incorporates mobility and vision as well. Architecture for him had to be light on its fight and had to design with light, well before lighting as art for James Turrell and Dan Flavin. Naturally his culminating projects were Vision Machines. Naturally, too, they drew on the science behind "how we see" in order to stimulate hallucinations and dreams.

That science seems all but incomprehensible today, although a typescript spells it out in brutal detail. It turns, though, on the interaction between a machine and a human subject, much like AI art now. It gives new meaning to design correlation, as correlation between the mechanical and human, and it issued in a Correalism Manifesto. Rather than a mirror or window onto nature as a passive subject, Kiesler saw his work as "activating the active object." He divided his design for Peggy Guggenheim into spaces for abstract, surrealist, daylight, and kinetic art. He thought of film itself as "photographs in motion."

Interactive art has high aspirations even now, as with Rirkrit Tiravanija and relational esthetics. Yet it is not easy to replicate in a museum. What a show once called "theanyspacewhatever" may be nowhere at all. The curator, Mark Wasiuta, is left with display after display of the sketchiest of plans and sketches. Kiesler gets off to a strong start with the mobile bookshelves and a screen for films. Yet the library still bars visitors as it twists ever so slowly in the wind.

Just two more rooms follow, as if to rub in Kiesler's broken dreams for contemporary living. His biomorphic Endless House never began—or at least never got past a 1958 model, seven years before his death. He called picture frames "deadening," in contrast to the active object, but they do offer something to contemplate. Most good art is very much the active object, but it can also slow time and take time to come to life. His own art is well worth rediscovering, but it may not take all that long. Better grab a book.

Sonia Delaunay ran at Bard College Graduate Center through July 7, 2024, Frederick Kiesler at the Jewish Museum through July 28. Orphism ran at The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum through March 9, 2025.