4.23.25 — Moonlight and Chilly Air

Infinite longing. One expects a decidedly romantic idea of Romanticism or nature after a stop for Caspar David Friedrich and lost souls. It also just happens to define Romanticism for Anita Brookner.

Brookner’s Romanticism and Its Discontents puts the emphasis squarely on the discontent. Her introduction to nineteenth-century French art and letters comes off all too pat and Romantic itself. Still, Romanticism truly deserves a survey as heartfelt and concise as this one. Last time I drew on past reviews of Friedrich at the Metto prepare you for its full retrospective, through May 11. Let me now place him in context of French and German Romantics, with an invitation to read more.

Brookner’s Romanticism and Its Discontents puts the emphasis squarely on the discontent. Her introduction to nineteenth-century French art and letters comes off all too pat and Romantic itself. Still, Romanticism truly deserves a survey as heartfelt and concise as this one. Last time I drew on past reviews of Friedrich at the Metto prepare you for its full retrospective, through May 11. Let me now place him in context of French and German Romantics, with an invitation to read more.

A movement so epoch-making may sound like an easy success. For Brookner, though, Romanticism means dealing with failure—and failing badly at the attempt. Her creators represent as many ways to cope with uncertainty. Some escape into idealism, art, and the Classicism of their teachers. Others look to determinate causes in science and humanity. Most found a hero in Napoleon. Each ends up with hardly more than a struggle, fatigue, and fancy ideals to which he himself puts the lie. Or so goes Brookner’s chilly romance.

Modern critics have opposed Classicism to Romanticism, using more contrasts than I care to remember—linear versus painterly, theater versus absorption, wilderness versus culture, primitive versus pastoral, authority versus community, aristocracy versus big industry, villa versus garden, and goodness knows what else. Perhaps only manifestos, historians, and art critics believe in periods anyway. Rebels against Jacques-Louis David, Voltaire, and Denis Diderot kept the revolutionary ideals of the first, the skepticism of the second, and the irony of the last. Nicolas Poussin and Poussin’s landscapes take Classicism into the Baroque with all its temptations intact, Delacroix paints like a Romantic while proclaiming his classicism, and J. D. Ingres echoes David’s line and idealized virtues while adding electric colors and an arm that manages to grow out of a sitter’s chest. One could debate forever whether Modernism ever outgrew Romantic individualism and a culture of capitalism.

Look again at Friedrich’s lunar vistas or the sea, with a dark clarity still visible in landscape art today. He and his countrymen celebrated not the unattainable, but a world newly at hand. One enters past maps of the lunar surface of incredible precision and beauty. Friedrich knew a little astronomy, too, when he included a ring around the moon.  Earthshine, reflected light, makes visible just slightly more than half the moon. I imagine that scientists then would have told me just how much more.

Earthshine, reflected light, makes visible just slightly more than half the moon. I imagine that scientists then would have told me just how much more.

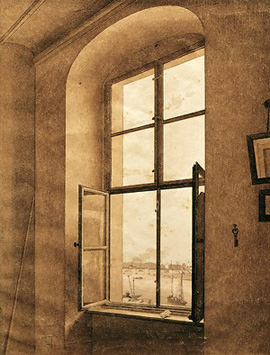

Whatever the world, Friedrich invented it at its most luminous. He takes in a river or harbor scene around 1805—at age thirty-one, with a finely wrought view from the artist’s studio. Later a ship’s mast belongs to Woman at a Window, a painting of his wife from 1822. The mass reinforces the stasis and geometry of the window, shutters, and wall. Nothing else comes close to the deep red and green streaks of her dress seen from behind. Somehow she stands out from the same colors and handling, slightly toned down, in her surroundings.

Is that mix of public and private worlds what really drove Friedrich’s men to the woods? Nature lay close by, even to a city boy—too close by. Progress threatened to uproot nature, just as a massive tree trunk stands torn from the ground and erosion has left a protruding rock to survive the elements. It threatened to break forever the intimate link between humanity and nature. Fortunately, one still has artists and the imagination.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.

Northern Renaissance

Northern Renaissance