Alias Modern Art

John Haberin New York City

Man Ray at the Jewish Museum

Even in 1913, Williamsburg had emerging artists. Man Ray for one emerged from there, and he emerged quickly.

That year the Armory Show brought Nude Descending a Staircase to America—and with it the scandal of modern art. Within two years, Ray began the most ambitious work of American Cubism, The Rope Dancer Accompanies Herself with Her Shadows. A year later he pretty much single-handedly created an American Dada. Five years after that, he was off to Paris, where he transformed photography. "Alias Man Ray: The Art of Reinvention" tells the artist's story as one of constant self-invention.

Perhaps it has to tell that story, for a man born Emmanuel Radnitzky. Perhaps it has to tell that story, too, as the Jewish Museum. The eldest son of Russian-Jewish immigrants, Ray faced the usual dilemma of cosmopolitan and Jew. Then again, the dilemma of assimilation and exile could explain the whole idea of an avant-garde. Ray's life in fact unfolds quite smoothly, and his reinventions fit just fine within the story of Modernism. No wonder a gallery retrospective over ten years before told much the same story.

The art of two dimensions

The Jewish Museum starts right out with the reinvention. It gives more than the customary space to Ray's early work, often dismissed as derivative. It also starts with half a dozen portraits of the artist—one at his bar mitzvah in 1893. The curator, Mason Klein, points to the influence of J. A. D. Ingres in another, a self-portrait in spare, broad strokes of ink. Pablo Picasso contributes another. And then another self-portrait applies white curves like star tracks to a blurry photograph.

One already has in miniature the evolution from Jew and conservative art student to a Cubist's eye, Surrealist photography, and the photographic object. One can keep looking to the artist's Jewish origins for signs of continuity and transformation. Does the name Man Ray (not to be confused with William Wegman and his dog) sound like a work of poetry and a photographer's fascination with light? The artist's father, Max, had already changed the family name to Ray and called the boy Manny. With only a slight change, the anonymity of assimilation becomes the breadth of all mankind. It also hints at Dada's disdain for self-expression and identity.

The family had intellectual ambitions, too. Max worked in a garment factory and as a tailor, but Man Ray went to art school, and his mother wished him to become an architect. In turn, her son made a tapestry in 1911 from his father's clothing scraps. In its shades of black and white, like pixels, the Jewish Museum sees hints of more human figures. Here, too, a portrait looks to the past, only to shatter it. A tapestry grid also predicts the Modernism of Sonia Delaunay and the recovery of folk art today.

The young man sought out modern art even before the Armory Show, at gallery 291, where Alfred Stieglitz soon launched another great example of Modernism in America, Georgia O'Keeffe and O'Keeffe drawings. And Ray was sopping up influences. The self-portrait in ink evokes Henri Matisse as much as Ingres. Landscapes the year of the Armory Show imitate Fauvism. He picks up on political change and contributes to a radical magazine. His largest early canvas packs human unrest into two colorful dimensions, like a mural by Diego Rivera.

Its culmination comes with The Rope Dancer, both an exemplar of and a metaphor for modernist drawing. Large fields of color with irregular borders animate the picture plane. The dancer appears above them, outlined in white. Her rope multiplies and surrounds her, and the poetic title appears at the lower right in place of a signature. Ray has also been illustrating books of poetry, and he already has a way with words. Who knew what dropping just two letters from Manny can do to a name?

He is caught up in ideas. An article insists on "The New Art of Two Dimensions." Except for The Rope Dancer, flatness and elegance can deaden his experiments in Cubism—much as it often did for the School of Paris in the 1920s. Did Ray recognize his limits? Maybe or maybe not, but no matter. He could reinvent himself again, in Dada, photography, and Surrealism.

Awash with angels

A self-portrait of 1916 combines the essential features of Dada, in its wit, assemblage, and mockery of the artist's ego. The twinned metal of a doorbell forms its eyes and a buzzer its navel, while a hand print marks its chest. Is it again continuity or transformation? One could ask the same thing about his first photographs. Ray weaves together an eggbeater and its shadow. He takes the found object of anti-art, and he gives it the translucency of his rope dancer.

He also chooses a new country. The Armory Show brought Marcel Duchamp to New York, and Duchamp in turn welcomed Ray to Paris. He feels right at home in a community of artists, writers, and exiles, including James Joyce and Gertrude Stein. He becomes their photographer, too, with stylish portraits of an age. They reflect his fascination with doubling, as in a self-portrait with camera. They reflect, too, his fascination with shadow, as in the photographic image reversal known as solarization, an influence on Foto-Cine Clube Bandeirante in decades to come.

A letter to Tristan Tzara, the Dada poet, shows his ambivalence about what he is leaving behind. "Dada cannot live in New York. All New York is Dada, and will not tolerate a rival." Perhaps neither can he, and he thrives on rivalry. He and Berenice Abbott photograph one another. He helps build Duchamp's cross-dress identity as Rrose Sélavy—or, as Ray titles one print, Cela Vit ("this saw" or "this lives").

Again, he combines continuity and transformation, naturally including a visit to Picasso's studio, if not to The Red Studio of Matisse. Even when he adopts the threatening stance of Dada, as with a gun suspended from a magnet, he lends it elegance and humor. The black, nail-studded iron of Gift suggests a nightmarish present, but also a free exchange worthy of cultural anthropology. The metronome with a ticking eye bears the titles Indestructible Object and Object to Be Destroyed. You decide. A sense of beauty also goes perfectly with the evolution from Dada to Surrealism.

A clothesline makes me think of a much later poem by another American, Richard Wilbur: "The morning air is all awash with angels." An accidental discovery, the photogram, extends the poetry (although László Moholy-Nagy was making photograms, a term that he coined, at the Bauhaus in 1922). Here Ray exposes film in direct contact with the object to be recorded. The rebel names the rayographs after himself—and makes some of his first on commission, for the Paris electric company. Again one cannot pull apart the found object from transformations into art.

Faced with the Nazi invasion, Ray chose Hollywood before a postwar return to Paris. As with Wassily Kandinsky during World War I or Marc Chagall after World War II, exile risks nostalgia for the recent past. As with an aging Picasso, an art of reinvention risks falling behind the inventions of others. The jokes and poems keep coming, but they grow leaden, and a return to painting weighs them down that much more. Ray gets one last great image, a billiard table angled to the clouds. But an art of continuity and self-transformation finally stumbles on the disruption of war.

Not so silent music

As an American in prewar Europe, Ray might stand for two Modernisms—the stuffy institution and anti-art. He had the versatility to pull off both, just as he could work in oils, drawing, and photography. He created assemblage before it had a name. A chandelier of coat hangers casts still more dancing shadows against the wall and over a suitcase on the floor, like a refugee's lost luggage. They would look at home in a gallery today.

Verbal facility holds all that experimentation together. It mixes poetry and humor, like a joke too dazzling to spoil by laughter. It gives assemblages the bite of Dada and the allusiveness of American Surrealism and a Surrealism beyond borders. It echoes in the titles of work like The Rope Dancer or, for a particularly dark image, Retour à la Raison ("Return to Reason"). In a late interview, the artist recalls his first days in Paris, knowing hardly a word of the language—much as his father must have arrived in South Philly with hardly a word of English. In no time, he was punning in French.

Art is supposed to be mute. But Ray is a talker, and his love of words helps explain the ghostliness of his images. His colored planes learn to dance, as Cubism's thrusting volumes do indeed become shadows. Rayographs, too, start with something direct and physical, an object in contact with the medium, but they resemble phantoms. Imagine x-rays that peer into a body only to find that it has disappeared, like a portrait after the dead. That, too, is a kind of doubling—like a portrait of Stein next to her portrait by Picasso. Solarization turns Duchamp's profile, with gaunt and impressive cheekbones, into an icon and an enigma.

A decade before the Jewish Museum, the late Andre Emmerich gave Ray a very fine, if small, retrospective. There, too, the curator's informative notes added enormously without editorializing foolishly. And there, too, one could see just how much Modernism was to change before its center could shift to America. Ray made an interesting contrast to the same gallery's show six months later, the neo-Dada of Yoko Ono. His dexterity also made an interesting contrast with the sober American abstraction of Oscar Bluemner. It took a move to Paris to complete the self-creation of a New York modernist, and there was no turning back.

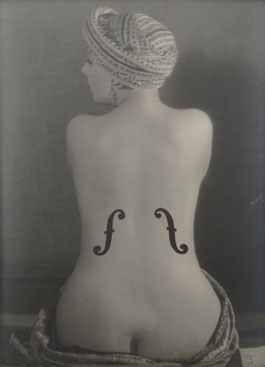

Ray relied on traditional media more one might remember, and the photographs take a traditional view of female beauty. In the Violon d'Ingres, a lover's nude's waist seen from behind follows the f-shaped outlines of a violin's sound holes, and a scarf covers her hair. A violon d'Ingres means a hobby, to the point of obsession, and Ingres relished nudes with the allure of orientalism. Through his title and subject, Ray parodies art's old obsession with women as subject, while obviously relishing it. He had an affair with another American photographer, Lee Miller, who came to Paris looking for him.

He left one signature work after another, in a small and abbreviated career. Hitting everything out of the park comes at a price, of not being terribly good at singles and running the bases. The somber paintings serve as a reminder that "School of Paris" today often means conservative. So in their own glorious way are the rayographs. Ray turned photography inside out, but as modern painting—part of why photograms today have a newfound popularity, going back at least to Patti Hill. As the century gets a fuller history, maybe even conservative in art can take on new meanings, and so can Modernism in America.

"Alias Man Ray: The Art of Reinvention" ran at the Jewish Museum through March 14, 2010, "Man Ray: An American Surrealist" at Andre Emmerich through December 20, 1997.