Don't Look Back

John Haberin New York City

Diane Arbus

The strangeness of Diane Arbus only begins with her subjects—the geeks and transvestites, the giant and the children almost like dwarfs. It includes her uncanny ability to entice her subjects to look back.

It is not the pampered, composed look of a celebrity. It is not the shameless look of street hustler or the endlessly beseeching look of a teenager, seeing the lens and longing to become a star. It is not the bored look of someone for whom spectacle has displaced reality.

Has it really been fifty years since a retrospective, only months after her suicide in 1971? And was she really little known beyond photographers like herself before it made a sensation at the Museum of Modern Art? Her name was already a byword for strangeness when I saw her at the Met in 2005—there, too, in the hands of John Szarkowski, MoMA's legendary curator of photography. Now, in 2022, a Chelsea gallery recreates the earlier show as "Cataclysm: The 1972 Diane Arbus Retrospective Revisited." Wall text revisits its impact on critics and the public as well. I shall do my best here to consider them all.

Many photographers strongly identify with their subjects. Larry Clark, for one, locates his subjects' strangeness in illicit desires and acts. He removes them from familiar surroundings. A generic rootlessness, he implies, lies everywhere in contemporary America if one only paid attention. Finally, he thrusts all that right in one's face. He demands and refuses judgment.

Not her. The regard in an Arbus print begs for judgment of everyone present but the sitter, but it questions your judgment as well. That look, that invitation to the camera to do its worst, still presents a challenge. It obliges others to remember that they are looking, too, even when they blame the photographer for lingering on the freak show. It demands that they ask repeatedly just who is revealing what to whom.

Who are these people?

Arbus did not always work that way. In her first solo efforts, from the late 1950s, she captures her subjects in passing, more like Robert Frank in The Americans than Danny Lyon or Gordon Parks in their intimate acquaintances. Perhaps she did not know them well enough yet, or perhaps she knew photography too well. Walker Evans had his "American photographs" and prowled the subways, his camera hidden beneath his coat, and Duane Michals has his words and pictures and his Empty New York. Art photographers had sought that "decisive moment," and photojournalists had walked the streets day after day. A fixation on the bizarre may already suggest documentation—whether in Leonardo's drawings and unfinished paintings or with Weegee, holding out his press pass and bulky flashbulb.

Arbus knew all that. She studied with Berenice Abbott, who had worked for Man Ray in Paris and had sought beauty in a changing New York, like Bruce Davidson still to come. Arbus grew up in the city, back when it was a newspaper town, before "the last newspaper." Her brother, Howard Nemerov, called one of his early poems "The Daily Globe," after the Boston daily in which "the characters in comic strips / Prolong their slow, interminable lives / Beyond the segregated photographs / Of the girls that marry and the men that die."

Soon, however, she notices that her subjects notice her, and by the 1960s people pose for her, as they will for the rest of her life. Her changing practice could reflect her exposure to the norms of fashion shoots that Cindy Sherman and others have since trashed. Arbus and her husband had partnered in the business as early as 1946, working for such magazines as Vogue and Glamour. For her own first commissions, starting in 1960, she turned to Esquire and Harper's Bazaar. I wonder if they realized what spectacle they had chosen.

Fashion, in turn, had its lessons to learn, just as for Joel Meyerowitz. One may spot her frontal poses and unflinching gaze later, in the work of Richard Avedon. Arbus even left black strips on her prints for a while, like Ray K. Metzger or Avedon until his death. But no one cherished blackness as much as she—so much that she moved it all into her subject. The exhausting reverence of the Met's retrospective can at times seem less a whitewash than a service for the dead.

Art, photojournalism, and fashion may serve as reference points, but they cannot define her style. They may suggest why she sought that uneasy closeness to her sitters. Like them and so many others, she was coming out of hiding during the 1960s. In her husband's business, she had put much of herself on hold to serve as the stylist, almost like the burlesque acts she was to seek out in their dressing room. Now separated and well into her thirties, she was taking up the camera fully on her own. She studied again, this time with Lisette Model, who taught that a photographer must have a passion for her subjects. I wonder if she knew from Lewis Carroll what kinds of passion for its subject a camera can reveal.

None of that, however, can get at the fascination of others—on both sides of the camera. No wonder she turns so often to double portraits, of pairs that may or may not be twins. Who are these people, and why do they want so much to put themselves on display now? Who is she to look, and who am I to look now? Arbus does not just oblige one to ask. She is asking herself.

A larger theater

Arbus's sitters feel compelled to look, compelled by the very roles they assume. Sometimes, but only sometimes, that involves a casebook compulsion, as in the lives of cross dressers and sadomasochists. It involves the very logic of performance. In the 1950s, she snaps people in theaters, in front of a movie screen, more shadowy than the fictive lives within. She has created untitled film stills before Sherman.

Before long, Arbus penetrates the screen to performers off-stage. But were they ever just performing, or were they ever not? She enters a theater's dressing rooms, much as William Eggleston penetrated Radio City, but she never follows her actors on stage. She does not have to follow. Their performance comes into its own only when they emerge onto a larger theater. Parental guidance still suggested.

Arbus finds the artificial lights and dark shadows of stage and film in a city street. She finds its shallow stage in the constraints of New York City apartments. She shows teenagers in love, posing as a couple. They want so much to grow into their adult role, just as they are growing into their oversized topcoats. They have yet to learn how to make their faces betray affection to the camera. Perhaps they do not know yet how to see it in each other or in themselves.

The graininess of photojournalism gives way to increasing crispness, but not in order to define a coherent deep space. A flower seller appears trapped by the glare of headlights or by the night. A man stands lost in Central Park as if in a vast nowhere. Tall bare branches frame the frailness of Jorge Luis Borges as if eating into his flesh. Along with Abbott, Arbus could serve as the consummate New Yorker, but with the city as backdrop rather than as landmarks or as home.

She has found the set for a performance created solely by her and its actors, with their dearest possessions the props. Buildings may fade out of focus, but not a stuffed dog or those plastic flowers, held out for sale like a vain and lifeless gift.

Arbus moves easily from a performer with his head facing backward, a headless woman, or a human pincushion to children ballroom dancing for the prize. It seems only a short step from pinup girls in their dressing room to a barbershop with pinups between the mirrors. Each lives by its rituals, and what good are rituals if no one is there to bear witness?

Ceremonies and betrayals

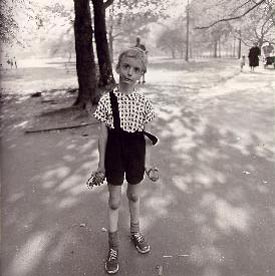

She wants, she writes, to capture "the considerable ceremonies of our present . . . because they will have been so beautiful." She does not, however, leave performers in full command of their performance. She will not let them stop watching her, and she often waits until they forget that she in turn is watching them. For a moment I wondered: could I have been that child in the park with a toy grenade?

They may not turn away from the camera, but they often lose patience with or hide from each other. Her "Jewish giant" seems unreal not merely because he has to bend over to fit in the room. One may look at him with astonishment, but not half as much as he and his own parents regard each other. The number of eyes even within these multiple performers far exceeds the number of performances. Any easy interpretation simply adds one more set of eyes.

Her own motives come up again and again in interpretation. Critics have seen her work as exploitative or sympathetic, violent or erotic, the projection of a fragile mind or the creator of a family. In reality, she makes one question one's own motives and those of the photographer as much as the subject's. The Met titles its retrospective "Revelations," and I dare one to decide what it reveals. A print—or a museum—becomes neither fully public nor private. Every display, along with every act of looking, takes on unintended consequences.

Arbus is at once complicitous with each life as with a crime and in violation of her sitter's complicity. "I used not to notice the slightest difference," she writes, "between people and things." To Susan Sontag—ever the guardian of photography as witness—Arbus's village houses only idiots. I might call her art instead an inspired autism. She could pass for an extraterrestrial, fascinated by the strangeness of Earth, knowing that she, too, remains unforgivably alien.

Perhaps she always was. She attended good, reform-minded private schools, married young, had a child, never went to college, divorced, and died at her own hand. She did her own printing up to her last years, another uncertain mark of her distance from others.

She could certainly seem alien, at MoMA or in the Met's spooky sideshow, broken by dark alcoves filled with memorabilia but oddly reluctant to talk about her personal shadows. The exhibition passes over her life and work with her husband, as if unwilling to raise too many demons. It includes contact sheets, prints by others, and even prints she never intended to be made, but with no obvious betrayal of quality or her artistic persona. Then again, when it comes to Diane Arbus, betrayal is a loaded word.

Small faces

Arbus had a feeling for the ordinary, even if she pressed that concept to extremes. A later exhibition breaks not just with the Met but with my own conception of her to complete the picture. It could almost make her subjects' direct connection to the viewer less disturbing, but no less haunting.

The exhibition title puns on Truman Capote's first novel, "Other Faces, Other Rooms." He, too, knew how to turn a character study into a freak show and a freak show into a study in human intimacy. One remembers not the rooms but the people. As with Capote's book, too, Robert Miller gallery brings out the tender, fragile side of an artist known far too much for dress-up poses and drawn-out shocks.

In that gallery exhibition, Arbus often works in a dark street, a darker movie house, or a bedroom. Even in pairs, the characters seem cut off from the living rooms, dressing rooms, and public parks in which so many of her subjects keep up appearances. Where so many of her subjects, too, dare one to look or to look away, here one feels a plea that perhaps someone will keep looking. Often in her work, people seem dangerously self-contained. Here, she often projects a physical as well as visual intimacy.

As usual, she rarely catches people on the fly. She prefers to establish rapport and to ask her subjects to pose, but she gives precious little help in doing so. They look ordinary, in dark street clothes or in nothing at all. They cling to one another, sometimes in bed, rather than to the viewer. They turn hesitantly toward the camera or hesitantly away. More than ever, they seem to plead for attention, not as a matter of vanity, but in search of support.

As so often with Arbus, then one looks again. One cannot help oneself. In that couple, one is masturbating the other. In the shadows, anything can lurk—perhaps even the figures from her retrospective.

In bringing to light unrecognized subjects and divided points of view, Arbus has something in common with Garry Winogrand and Lee Friedlander, and MoMA famously exhibited them together in 1967 as "New Documents." In the words of the curator, they were taking documentary photography from the social and political "toward more personal ends." Like them, she documents the shifts underlining the 1960s, when personal tensions went public and merged with politics. A big-eared geek clings to his country, his pro-Vietnam War buttons, and his hopelessly crooked bow tie as if to any hope of belonging. Peace protesters look like ghosts feeling their way in the dark.

Invisible things

Arbus cares too much for the fringes of life, including old age and childhood, to belong entirely to either side in a budding culture war. She spoke about admiring a show of Walker Evans until she returned to see and to reject its primness, and who is to see which reaction is more revealing? Instead of the baby boomers' coming of age, she photographs elderly debutantes, still dressed as if for their coming out. She converts a suburban nudist colony into an aging parody of a love-in. She prefers the moment of preparation for a performance—or its remembrance decades later—to any transient illusion of wholeness.

She has had obvious influence, as in the sordid, personal documentaries of Larry Clark, Peter Hujar, Ryan McGinley, or Sam Taylor-Wood. However, those photographers beg to appear as both members of the scene and recorders of degradation. One may call them cool or revolting, brutally honest or in self-denial, but one always gets to judge. Arbus stands as neither insider nor outsider, self-indulgent nor outraged.

She does not claim superiority to either her subjects or to the viewer—and in turn she allows the viewer neither belonging nor detachment as well. I can hardly imagine her beside today's round-the-clock TV coverage of celebrity and death, in which photography as witness creates its own culture of exploitation. Arbus would document that personal moment before a performer hit the stage that was so often a mystery to the audience. Today it seems like almost every celebrity from Gene Simmons, to Kathy Griffin, to J. Cole has a reality show that purports to reveal the exact moments that Arbus has captured on film.

A point of view either inside or outside would allow for generalizations. One identifies Arbus's photographs so much with their subjects because she takes each as an individual. Only an individual, after all, can aspire to the literally eccentric. In high school, she criticized Plato for his belief in universals, his distrust of the unique. Rather than the perfect moment, she cares more for the lingering imperfect that others have passed over. As her brother put it in another poem, "The world is full of mostly invisible things."

Like Plato, however, she never knows for certain what in this world to call an image or a fiction. "The world," she writes, "is full of fictional characters looking for their stories." Even in betrayal, she believes in her characters and their stories. She wants, she insists, to "believe in something," especially when the world would scorn it and turn away. "Everyone doubts, she writes, "any dumb but pregnant comment, any criticism of the world's arrangement" as merely "eccentric." A "dumb but pregnant comment" could almost define photography.

The Met's retrospective ends with perhaps her most portentous-sounding quote: "photography is a secret about a secret." Then again, once one tells a secret, it is no longer secret. And those who listen to a secret may find themselves burdened with it for good.

"Diane Arbus: Revelations" ran through May 30, 2005, at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, "Other Faces, Other Rooms" at Robert Miller through October 15. David Zwirner revisits her 1972 retrospective at The Museum of Modern Art through October 22, 2022. A related review looks at early Diane Arbus.