4.11.25 — O Brave New World

If one thing comes to mind about the Middle Ages, it could well be stasis. What could disturb centuries of ritual, art, and ideas? What could disturb the darkness?

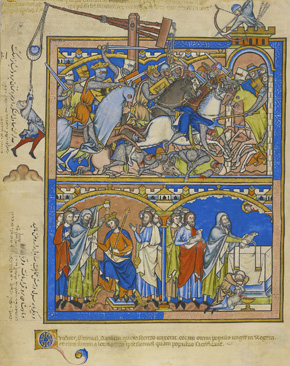

With The Book of Marvels, the Morgan Library traces not just the end of an era, but something more. In reality, the world itself was changing, and travelers were catching up with the changing picture. As the show’s subtitle has it, they were “Imagining the Medieval World,” and they invite you to imagine it as well, through May 25.

The Book of Marvels contained many discoveries, and so did the medieval journeys that preceded it. The Morgan does not stop with that one book, not even in the small gallery off the atrium. A modern marvel itself on its hundredth birthday, the museum holds the travels of Marco Polo to the East and Christopher Columbus—who published his own account of, he still believed, a shorter passage to India. It has the legend of John Mandeville, an almost surely fictitious Englishman, that may have first appeared in French. They witnessed men with six arms or two heads and bearded women. They found Asian spices, fabrics, teas, and the entirety of Islam.

O brave new world that has such people in ‘t. So goes a memorable line from Shakespeare’s The Tempest, from a girl whose discoveries, of flawed and altogether normal people, came by sea to her. As her father replies, chastening, ‘Tis new to thee. But then it is only a fiction, and so are the claims with which I began. Far from static, the Middle Ages had its philosophical changes, as Aristotle gave way to original sin, and its political ones, as Rome lost its dominance. It strayed from home for the Crusades to the Holy Land. Trade routes to the Middle East and Asia were opening up as well.

The show’s premise is suspect as well, although interesting. The travels of Alexander the Great and Pliny belong to the ancient world, not the medieval one, and The Book of Marvels, from the 1460s, or The Book of Nature, from 1475, to the Renaissance. Columbus obviously wrote after 1492—and not about India after all, but rather a true brave new world, the Americas. And will it be about the day-to-day world that men and women knew or about imagined marvels? If it has mostly anonymous artists without the true wonders of illuminated manuscripts and medieval bibles, it has the interest of actual lives, hunting and exploring. Someone had to push against the limits of the medieval world.

Just this past fall, the Met staked its tale of the early Renaissance on Duccio in Siena, at the center of new trade routes. Where would a curator stake a career, after all, without a contrarian’s history? The Morgan’s curator, Joshua O’Driscoll, has his fictions as well, but also insights. He grounds the show in both ways of discovering one’s own world, imagining and mapping. In different ways, they create and reflect the hierarchy of late Middle Ages and its giving way to something new. Already the appreciation of marvels suggests the advent of science, trade, and an openness to discovery.

The imaginings are themselves anything but the European church triumphant. The most vivid colors come with black African skin and Persian Islamic art. The many nudes are neither demurely shrouded nor Renaissance heroes. At the same time, a hierarchy appears in depicted wealth and architecture. Those nudes arrange themselves frontally in a several story building. They know where they belong.

Maps may seem more like historical curiosities than art, but they are just as revealing. A guide to the Crusades looks like a treasure map. Later ones show a closed world, but a world that contains multitudes. An encompassing sea forms the picture’s borders. It may consciously invert the ancient view bounded by the shores of the Mediterranean, as in the Odyssey. It may be a brave new world after all.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.