A Market for Defiance

John Haberin New York City

The 2012 New York Art Fairs I

Just when you thought the noise of the art world had died down a bit, there come the art fairs. For 2012, that second weekend in March brought the most noise and clamor yet. Stranger still came a dramatic postscript in May. An accompanying article continues the story then, with a British import, Frieze, and the Hamptons in summer—along with fresh debates over who hates them most.

But there was something lurking beneath the noise—or because of it. Surely, if Morley Safer were to go looking here for a sham, as in Miami for Sixty Minutes, he would find it, right? But nope, the entire weekend felt less bloated, perhaps especially at the top end, than earnest and diverse. Competing fairs had competing visions of an art scene that has become all about differing directions and competing markets, rather than a canon. Amid it all, one with nothing more than new media, Moving Image, ended up the most representative of all.

Where the action is

Their March number had climbed to twelve, although a Miami invader, ArtNow, dropped out just in time. A hotel desk clerk near Madison Square still had to fend off inquiries. They started early, on a Tuesday, when the Art Dealers Association of America held its gala evening for the Art Show, in the Park Avenue Armory. Needless to say, you and I were not invited. They threatened to last until May, when Verge and Pulse, choosing not to compete directly for foot traffic (apart from promoting a walk to some New York participants), have finally scheduled an appearance, to coincide with Frieze on Randall's Island. Better use the intervening eight weeks to catch up with reality or to rest up.

They stretched from West 57th Street and Twelfth Avenue, where Scope erected its tent three blocks north of the Armory Show, to the Lower East Side, where the Dependent offered hotel rooms to nearby dealers and others. They barely escaped north Brooklyn, where galleries dared one to skip Manhattan in favor of an evening walk, since of course the game is rigged. At least they did except for Luhring Augustine, which just happened to have opened a Bushwick branch of its upscale operation. At least they did, too, except for another recent invader from Chelsea, Slag, which exhibited a figure painter, Dumitru Gorzo, at Volta NY. That gave Bushwick its first booth in the fairs, unless one counts NURTUREart's setup in Volta's cafeteria. Then again, the neighborhood still defines neighborhood loosely, and the walk would have taken anyone past midnight had the art only complied.

Still, defiance shapes the actual art fairs as well. As the fairs have grown, they are no longer about exclusions and inclusions, but about competition. Once the Armory Show meant something, including the armory. Dealers who could not quite afford it might have settled for Pulse, perhaps, and artists who could not quite find a dealer might have settled for Verge. Heck, the latter even invited me to talk. Already, though, one had signs of much more at stake.

One could look to the 2009 art fairs and 2011 art fairs simply for signs of recession and recovery. And yet the real story has changed to competition—more specifically, to competing models of where the action is, to the point that some have declared fall openings obsolete. The Armory Show has its two Hudson River piers in midtown once again, one "modern" and one "contemporary," and one can make a game of who counts as safely dead and who as truly contemporary. I trust that Fred Sandback at Susan Sheehan, Thornton Dial at Andrew Edlin, and Pat Lipsky at D. C. Moore enjoyed their temporary stay among the first, and I knew all along how much collectors appreciate having Jean-Michel Basquiat among them forever. Anyone as able to reinvent herself as often as Cindy Sherman fits in perfectly on both piers. So does Chuck Close, with the contrast between the early bold poses in black and white and his later grappling with age, disability, and his own hyperrealism.

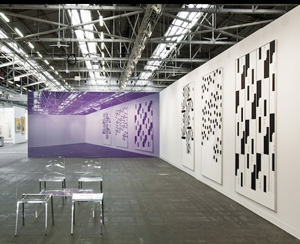

The Armory Show defines the action as the mainstream, now more mind-boggling than ever. One could have been using the afternoon to cover Manhattan. It has such newcomers with edgy reputations as Winkleman with lessons from Jennifer Dalton, Zach Feuer with open brushwork from Kianja Strobert, On Stellar Rays with monitors on the floor for performance by Clifford Owens, and another Lower East Sider in Eleven Rivington, with dense, lush abstraction by Jackie Saccoccio—whose solo show downtown was even better. It no longer even bothers with breaks for single-artist installations, although David Zwirner gave its space to site-specific abstract geometries by Michael Riedel, including three silkscreens and their mirror in wallpaper. It has its international cast, including a whole one-time wing for Scandinavia. I hope that whichever artist exhibits toilet paper labeled angst makes it available soon on college campuses for football weekends.

That leaves plenty of competing models. As a Whitney Biennial looks less and less obliged to declare the state of the art, while the New Museum Triennial grows leery of painting, all this waste of time and money may have a purpose after all. I know you never did think that the noise and clamor had died down, although museums in the recession have relied more often on their collection, like MoMA with German Expressionism and the Met with Frans Hals. A few weeks before, Gagosian had challenged one to see the "complete" dot paintings of Damien Hirst (with complete very much in quotes), and anyone who checked in at all eleven branches worldwide received a free work of art. (Another dot painting has landed at the Armory Show, under modern.) I wanted a similar prize if I hit all the art fairs, but I failed anyway because I miscalculated, for the Dependent ran one day only.

If you have to ask . . .

The ADAA's Art Show defines the action as quality, and then it tries to define quality. It does not do a bad job at that, and the air of exclusivity also pays off in a surprising peace and quiet. One could contemplate the calm expanse of Jennifer Bartlett, at Locks Gallery, before her more recent pastels or Dorothea Rockburne in her greatest years, at Greenberg Van Doren—from pleated white ground to stacked off-kilter squares of color. One could remember the dark abstraction of Romare Bearden in 1960, at D. C. Moore, just before his turn to collage. One could preview Sara Sze at Asia Society, thanks to Tanya Bonakdar, or the proud and anxious self-exposure in Francesca Woodman at the Guggenheim, thanks to Marian Goodman. I came to the photographs of Rudy Burkhardt as a discovery, thanks to Tibor de Nagy, in a 1940s' New York of artists, Coca-Cola, the Flatiron Building from above, and legs from below.

At the other extreme, Fountain defines the action as inclusivity, like Brooklyn on steroids. While the Art Show returns to the Park Avenue Armory that the Armory Show has left, Fountain takes the site of the 1913 Armory Show on Lexington Avenue—only the shock of Modernism has given way to the complacency of schlock. It also draws crowds that its competitors would envy, not to mention a band and a free local beer for those willing to endure the lines. Scope defines the action even more as an act of desperation, from American dealers outside New York or without a gallery. ("My parents call me independent," one explained.) Or one can ignore the dealers altogether, in favor of "the art of rum making."

Pool has taken up Verge's role, with artists obliged to rent a hotel room in hope that someone will cohabit with their art. Most of the artists were in town for the occasion, often from abroad, including at least one who did not speak English. I enjoyed Heather Van Uxem's sculpted spiders and dark stained wood, Samuel Gélas's paintings of displaced people in Guadeloupe, and an imagined alphabet of dented squares from Tim Roseborough—who allowed one to take home one's name, signed by him in ordinary cursive. Like Fountain, though, they stuck largely to painting, a reminder that the excluded rarely means the unexpected. Had the growth of major art fairs left no room for the edgy? Consider two more models for an alternative, neither of them on the cheap, plus an entire show for video that somehow encompasses them all.

Volta NY, which shares ownership and a shuttle bus with the Armory Show, nonetheless announces a focus not on commerce but on art. And, starting with the 2008 art fairs, it does so with a simple rule: if you show up, you show just one artist. This year's results included Andrew Masullo, one of the very few painters in the Biennial—but from Steven Zevitas, a Boston dealer, rather than Feature Inc. on the Lower East Side (and Masullo himself works in San Francisco). They included work as derivative as Karim Hamid's after Francis Bacon, from Aureus of Rhode Island and Basel, and as eye-catching but silly as Carl Emanuel Wolff's firecracker monsters, from Schuebbe Projects in Düsseldorf, but even they gain from the space. I may yet remember Jason Gringler's shattered mirrors as painting from Stefan Röpke in Cologne, Sheila Gallagher's painting in plastic from Dodge, Rachel Beach's abstract sculpture of reclaimed wood from Blackston (like Dodge, on the Lower East Side), videos by Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook of art students from Tyler Rollins, or Patrick Jacobs's peepholes onto constructed other worlds from The Pool NYC.

That leaves one last claim to an independent art or, more precisely, the Independent. Introduced by Elizabeth Dee and Darren Flock in the 2010 New York Art Fairs, it is still free and open late. It still occupies a shrine to late-modern idealism, the former Dia:Chelsea, and it will broaden almost anyone's horizons with visitors mostly from Europe, an art publisher, and White Columns, the nonprofit. It breaks boundaries right with its layout, as a kind of anti-Volta, with no booths at all. Artists run together, with labels all too few and far between. Gavin Brown even creates an installation from Rob Pruitt's silvered desk chairs and wheelchairs facing paintings and wallpaper by other gallery artists, with no seating allowed.

Accessibility, in other words, extends only so far. If you have to ask, you can't afford to appreciate it. Like a postmodern take on the the Art Show's exclusivity, the Independent runs to such London faves as David Salle for Maureen Paley and Oscar Murillo with his basketball as a wrecking ball for Stuart Shave. As with Jutta Koether's paintings and abstract photography by Wolfgang Tillmans at MoMA or by Ernst Haas or Eileen Quinlan at Campoli Presti, it shares a sensibility with the Whitney Biennial. Still, it can bring anyone up short, as with an immense swing by Andrea Bowers for Andrew Kreps or simply by leaving one at sea. Maybe critics and collectors, too, could stand to learn that they are not always in on the action.

Video fair game

Is there still anything special about new media? Is there even anything new? The art fairs still answer yes, and you can see why. Even if you do not believe that the media is the message, you may find it harder to sell before the collector moves on to the next booth. Fairs still depend on painting and sculpture—the fringe ones, paradoxically, because their artists never did break the mold. And that leaves room for Moving Image, a fair devoted to nothing else.

That second March weekend in 2012, it still had barely thirty artists and fewer dealers. Yet it filled Chelsea's Terminal Warehouse, for a medium that one can hardly hurry past. Video has many fathers—and at least one mother, in Charlotte Moorman, the cellist and performer who collaborated with Nam June Paik. They have offered many definitions of new media, for decades now, but all insisting on experience, in real time. With Paik one has the TV set as digital object, with him or Paul McCarthy the record of a performance, with Michael Snow or Doug Aitken a dismantling of perception with roots in alternative film, with Cory Arcangel or "<Alt> Digital Media" a primitive video game, with Cai Guo-Qiang or Omar Fast a tradition of documentary realism, and with Joan Jonas or Gary Hill a disruption akin to a philosophical debate. In its second year, Moving Image has echoes of all those strategies for today, but first and foremost video.

That second March weekend in 2012, it still had barely thirty artists and fewer dealers. Yet it filled Chelsea's Terminal Warehouse, for a medium that one can hardly hurry past. Video has many fathers—and at least one mother, in Charlotte Moorman, the cellist and performer who collaborated with Nam June Paik. They have offered many definitions of new media, for decades now, but all insisting on experience, in real time. With Paik one has the TV set as digital object, with him or Paul McCarthy the record of a performance, with Michael Snow or Doug Aitken a dismantling of perception with roots in alternative film, with Cory Arcangel or "<Alt> Digital Media" a primitive video game, with Cai Guo-Qiang or Omar Fast a tradition of documentary realism, and with Joan Jonas or Gary Hill a disruption akin to a philosophical debate. In its second year, Moving Image has echoes of all those strategies for today, but first and foremost video.

This was not the space of broken picture tubes—or, for that matter, fair booths. Identical flat-panel sets angled away from both tunnel walls, broken now and again for projections. Several dealers, like Bitforms or P.P.O.W. with its long commitment to David Wojnarowicz, have followed the medium for some time, and are still mulling its relevance to the present. When Ken Jacobs for Electronic Arts Intermix allows kaleidoscope patterns to break into a tour of his loft, Mary Lucier for Lennon, Weinberg into a Japanese monastery, or Hunter Reynolds for P.P.O.W. into his record of AIDS, they seem out of a more hallucinogenic age. By contrast, the nestled reflections at the center of Yael Kanarrek's child on a swing, for Bitforms, serve at once as playground, digital clock, and fractal geometry. Even the museum-style labels suggest a proper survey of the state of the art.

Not that the artists are over their fascination with old genres—like Jenny Perlin's retro FBI typist for M+R Fricke in Berlin, the agency's invasions of privacy mired in correction tape. Valie Export has her usual quotations of obscure pop culture with obscure implications about gender and oppression. Kelly Kleinschrodt for Carter & Citizen in LA makes her feminist statement with a bare neck out of a water perfume ad. Alex Prager for Yancey Richardson dresses for a curious combination of film noir and The Red Shoes before falling from a window, but her despair looks all the more haunting in deep color and slow motion. Josh Azzarella for DCKT simply projects King Kong onto three screens. Who knew that Hollywood's jungle had learned so much from the Romantic sublime?

The projections, when they do come amid the TV universe, serve as gathering points and natural environments. For Daniel Phillips of DODGE, it is a demolished paper mill, and for Janet Biggs of Winkleman (which did so much to organize the event), it is a natural history of predator and prey. Martha Wilson of P.P.O.W. insists on projection for its heightened scrutiny, for which she can in turn implicate the viewer. As she applies makeup to her own flesh, she insists, I Have Become My Own Worst Fear. As ever, Kate Gilmore for Braverman in Tel Aviv maintains a sense of humor about sex roles and art, as she knocks over paint cans shot from above, like Jackson Pollock stuck on scaffolding. When people gathered around a tale of extraterrestrials and a nature commune, by AES+F of Australia's Anna Schwartz, they cared less for the allegory than for the datedness and the theater.

Clearly Moving Image has not just more video art than other art fairs, but also more political art and more over the top. Do they go together, as for Miguel Angel's boy who lost his hands in the Colombian army, cleaning himself in woods, from Rojas Sicardi gallery in Houston? Are they evocative, like Sama Alshaibi's Palestinian from a Dubai dealer driving in circles while a head scarf billows outward; obvious, like Zhang Peili's remastered Chinese propaganda for Saamlung in Hong Kong; obscure, like Josef Dabernig's return to a South Caucasus writers colony for Andreas Huber in Austria; or all at once, like Christopher K. Ho's split-screen Lesbian Mountains in Love for Winkleman? Things can get silly fast, like Jaan Toomik's pose in front of a waterfall right out of Bill Viola, from Estonia, or Jesse McLean's slackers falling backward into each other's arms for Bushwick's Interstate Projects. Yet with a snail on a razor blade, from Jesse Fleming for LA's The Company, a shadow walking down the street, by Suzanne Hofer for Zurich's De Mayo, they can have a simplicity that old media sometimes forget.

The 2012 New York art fairs ran March 8–10 and May 3–7, and an accompanying article continues the story past March. The Hamptons had at least three art fairs in the second half of July, and NADA Hudson ran the weekend of July 28. Another related review reports on a panel discussion of "Art Fairs: An Irresistible Force?" After reporting for five years in a row now, plus more than once before that and after that, with the 2013 art fairs, 2014 art fairs, 2015 art fairs, 2016 art fairs, 2017 art fairs, 2018 art fairs, 2019 art fairs, 2020 art fairs, 2021 art fairs, spring 2022 art fairs, fall 2022 art fairs, spring 2023 art fairs, and fall 2023 art fairs to come, including Frieze, Frieze online, Art New York, and NADA.