Welcome Back

John Haberin New York City

The 2014 New York Art Fairs II

Welcome back, art fairs. It's like you never left.

Oh, I know, all that is old news. The art world can seem like one perpetual art fair, interrupted by auction news now and again, only moving from city to city. Some have estimated that sales from fairs now exceed those at the galleries, especially for top-tier galleries, and who am I to say? No sooner had a hurried weekend of fairs opened in New York in May, but emails went out touting booths coming soon enough to Basel. One had to read carefully to see which one was supposed to attend. This time, though, I really mean it, for now many a fair-goer need never leave New York.

Safety in numbers?

One may not have time to leave. The May crop has grown in only three years from an odd postscript to the weekend of the Armory Show in March to at least a dozen, featuring many of the same dealers. While Frieze New York, a London import, led the way, the May fairs also more closely reflect not just the international scene but also the city. One could say that galleries had hardly finished counting their money from one month before they were spending it on another, except for one thing: for all but the privileged, sales can come fast, slow, or not at all.

And that is the real story. Speaking only of global travelers and auctions is easy enough. It allows one to speak of an art world in the first place, rather than a diversity of struggles fully caught up in the real world. It allows one to identify art with a few pricey players, to simplify reporting or to bemoan the state of the art. Within a week of Frieze 2014, an art magazine devoted an issue to celebrities of all sorts, including James Franco. No wonder artists feeling left-out can identify with conservatives like Jed Perl, Robert Hughes, and Dave Hickey who argue that it is all a fraud, because "slow art" died with Andy Warhol.

Speaking that way is easy—and wrong, because it overlooks the aspirations of everyone, from top to bottom of the food chain. Fair reviews, too, mostly check off heroes and villains, much like an investor, as if they were fresh discoveries rather than business as usual in the galleries. I did much the same for the 2014 Armory Show and competing March art fairs. I could take special pride in having managed to attend them all. Suppose, though, that one tours the May fairs a little differently. Start instead with how things got this way, before asking what the different fairs hope to achieve.

The obvious culprit is money. Art's audiences have grown, as has the slice of the economic pie in the hands of wealthy art collectors and art advisors, so the number of exhibitions has grown as well, along with all the other constant flow of events that puts the emphasis on novelty and spectacle. That adds financial pressure to midlevel dealers, for whom fairs come at a steep cost, but also pressure to exploit every opportunity they can. The May round may actually present a greater opportunity, simply because it is not the hectic week of the Armory Show. One can step back from an exhibitor without bumping into a dozen other people or the art. The feeling of the real New York, as with NADA on the Lower East Side, makes the opportunities all the more rewarding.

Another obvious culprit is safety in numbers. When Frieze first came to New York, it stood out, and it still depends on seeming above the hoi polloi. It requires a ferry to Randall's Island, a steep admission fee, and even steeper costs to exhibitors—and it still aims for a global cast and big installations inside and around the island. One has to ask in advance for press credentials, and Frieze denied me. Yet it has also helped bring together alternatives, such as the Outsider Art Fair (formerly in January), Contemporary (formerly in October), and Pulse (formerly in March itself). And they, in turn, invite responses.

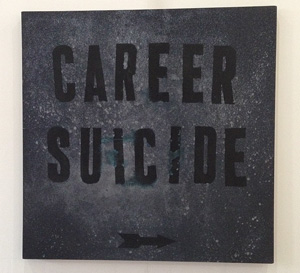

That includes personal responses. The very day after the Outsider Art Fair raised the profile of outsider art, Mark Flood took over a floor of the same building (the former Dia:Chelsea and, in March, the Independent art fair) for the Insider Art Fair. It was, of course, a display of his own, with his paintings after product logos (said to obey laws of evolution discovered in laboratory tests) and messages in black all but tailor-made for Christopher Wool—from Another Painting to Career Suicide. (Yes, you and I are duly chastened.) It was a convincing parody of fair extravagance, with black curtained "booths" (of trash bags), loud music, a smoke machine, and a couple in performance approaching cunnilingus. It was also part of his gallery show next door, including his past press clippings.

The pop-up fair

So you, too, can be an art fair, right? It can sure seem that way, and the results are not pretty. Flood points to one last culprit, in burgeoning pop-up spaces, open-studio weekends, curators padding résumés, aspiring dealers without a rent check, and DIY. They, too, demand a piece of the action, and it shows in May. Two "mini art fairs," Salon Zürcher in a gallery space in Noho and Satellite in Chelsea, amount to nothing more than small, unfocused group shows, as if the world needed yet another. Only barely a step up that food chain, several others have hardly a New York gallery in sight.

Verge boasts of being "run by artists, for artists," but it looks depressingly like business as usual in Soho, long after the adventure has left. Pool claims much the same, "based on the model of nineteenth-century French artist fairs," but if it ever got off the ground, I never found it—and the desk clerk at the hotel site had never heard of it. Select starts out with a gigantic replica of an old Kodak camera, by Daniel A. Henderson, pointed right at you, and who can resist the promise of a beer garden? (It turned out to be handful of cafeteria tables and a counter indoors, with Chelsea Manida's scented wax chandelier over the stairwell.) Still, booths often look more like poster shops. Even Henderson, who has also made an oversized Princess phone and a Selectric typewriter ball, seems motivated more by nostalgia than by playing, like Claes Oldenburg, at the edges of art and life.

Cutlog intends a gesture of defiance. It takes over the Clemente Center for Puerto Rican and Latino culture on the Lower East Side, with a room for resident artists and a sense of community. With Robert Montgomery's fluffy yellow ball hanging over the entrance, one can see right away good intentions and fuzzy, warm feelings. Inside, a winding space like a schoolhouse has a video room, two theaters, and alcoves where one least expects them. To keep you on your toes, White Box displays near Black Box. Overall, the fair leans heavily toward the brooding, cartoon-like outlines of street art, including Swoon herself, and before long it appears less radical than abandoned.

Still, homegrown fairs can be fun. Fridge has the instant appeal of a warehouse near the Long Island City waterfront, with some artist names in chalk on the floor, and the ticket counter shared space with cute pets up for adoption. (Across from them, Eric Ginsberg of Dorfman Projects had a dog painting.) Inside, along with t-shirts, the hit-or-miss displays had a fondness for gestural painting, such as Debra Drexler's eels and woman in green, Dean Radinovsky's large abstraction, and Danny Licoh's near abstraction with a figure out of Francis Bacon. Contemporary has an even better space in Chelsea's Tunnel warehouse, for a mix of furniture, jewelry, and single artists holding the fort, such as Yaro with baroque tables of found wood or Kathryn Spata in acrylic and gold leaf. The fair's handouts include marketing strategies for artists—and they will need them.

I missed Collective in the grand post office behind Penn Station, soon to be Moynihan Train Hall (my bad), but I welcomed the next step up the chain, in Downtown and Pulse. The first has the Lexington Avenue Armory, which looked so forlorn for Fountain in March and still veers off into darkness beyond the exhibitors. The latter has the Metropolitan Pavilion next to Select, looking brighter and more cheerful. Both, though, remember that the neglected can include familiar artists and worthy dealers. Both fairs, too, have galleries from all over town, with a sprinkling from other cities and overseas, but think of them as the "wrong" side of West 24th Street, across from inflated names like Gagosian and Mary Boone.

I missed Collective in the grand post office behind Penn Station, soon to be Moynihan Train Hall (my bad), but I welcomed the next step up the chain, in Downtown and Pulse. The first has the Lexington Avenue Armory, which looked so forlorn for Fountain in March and still veers off into darkness beyond the exhibitors. The latter has the Metropolitan Pavilion next to Select, looking brighter and more cheerful. Both, though, remember that the neglected can include familiar artists and worthy dealers. Both fairs, too, have galleries from all over town, with a sprinkling from other cities and overseas, but think of them as the "wrong" side of West 24th Street, across from inflated names like Gagosian and Mary Boone.

Downtown offered some big names on the secondary market, such as Frank Stella and Kenneth Noland (with Modernism) or John Chamberlain (with Jim Kempner), along with some dreary photorealism. Julie Blackmon (with Robert Mann), who knows when to let kids run wild, has managed to get them to walk in single file, after the cover of Abbey Road. Closer to discoveries for me were Richard Caldicott's abstract photography (with Sous Les Etoiles) and Sheba Sharrow (with Accola Griefen). Sharrow, now in her eighties, has a light palette but a dark history, with brushwork and figures that recall Nancy Spero or Leon Golub. Still, if I had to choose between the two fairs, I should go for Pulse for a clearer vision.

Nada is certain

Pulse has cleaned up its act considerably since its days west of Houston Street. This is the fair with Pulse Pause for its café, Pulse Play for video, Pulse Perspective for its guest speakers, and a Pulse Prize with a cash grant to one artist during the run. Thankfully, it does not call the bathrooms Pulse Privy. (Well, Aperture's photography books might pass for Pulse Publications.) It also promotes single-artist displays, with booth signs that name such artists right up there with the gallery, and it has Pulse Projects. These single works help one appreciate the roomy space and its artists.

Tamera Gayer painted her blurred color diagonals on the glass front, like tumbling skyscrapers. Charles Lutz's image of armed guards hauling money (with beta pictoris / Maus Contemporary) carries an obvious warning about the whole business of art fairs, if not also art. Andy Yoder's globe made from matchsticks (with Winkleman) shows the path of Hurricane Sandy, with an implicit warning about the tinderbox that is planet Earth. Within, at least two favorite dealers who have lost real estate found at least a temporary home. Among single-artist booths, Tegene Kunbi (with Margaret Thatcher) has broad horizontals like slabs of color for Sean Scully, but with the brighter hues of African spices and tapestries.

That leaves just one last step up the chain, short of Frieze and its excess, to the most welcome and ambitious of all. NADA earned a quick reputation as the go-to fair for the Lower East Side. It has not just the exhibitors to prove it, but a pier across the roadway from the projects (and I do not mean art projects). One might call it the anti-Armory Show, with an east-side pier, normally Basketball City, to the midtown blockbuster's west side. One can duck outside to take in the view of Brooklyn and Queens. Besides, it is free.

Maybe one should say instead the fair at which the Lower East Side dresses up. It even comes with a display of the NADA line from American Apparel. Intense lighting fills the vast interior. After Frieze, it is also the most international of May art fairs, and its New York contingent does go well past the downtown crowd. It has a long row of projects, here meaning starter spaces the size of a closet. Next time someone complains about rents for a workspace the size of a New York studio apartment, you have a rejoinder.

Things look good here—and not only because of the space and the company. Some galleries display merely the usual stable, like the lavish surfaces of Moira Dryer, Meyer Vaisman, and Jackie Saccaccio (with Eleven Rivington). Among projects, Saira McLaren (with Sargent's Daughters) brings stained color and metal dust to canvas, alongside her ceramics. In larger spaces, Karlos Carcamo (with Hionas) places modernist rectangles against shifting enamel fields, while Ana Bidart (with Josée Bienvenu) turns abstraction into a record of her travels, in lines that speak of bar codes, passports, and unspoken languages. Ethan Cook (with American Contemporary) divides a painting between white and bare support, their shared edges broken by imperfections, like Mark Rothko stripped of transcendence but not of contemplation. In his small bronzes, a ladder crumples rather than rises, leaving a fallen arch.

All is just fine, then, right? Artists can have their say, and fair-goers can have their pleasures, without so much as leaving New York. Still, the fairs are nonstop work, with at once too many rewards and too few. Too many, because it is all about rewards, and too few, because nothing, nada, is certain. Even prizes, an increasingly common fair marketing tactic, call attention not just to individual artists, but also to the economic tangle in which they work—sometimes pressured to produce new work specifically for the fairs. As New York in spring becomes a citywide festival more like Miami, where the sales are biggest, there may soon be nowhere left to survive or to escape.

These New York art fairs ran May 8–11, 2014, but with Frieze extending to May 12. Mark Flood ran at Zach Feuer through June 14. Separate reviews take up the weekend of the 2014 Armory Show and the May New York art fairs, including Frieze. Other related reviews report on claims for the death of art fairs after Covid-19 and a panel discussion of "Art Fairs: An Irresistible Force?" And do not forget the 2021 art fairs, spring 2022 art fairs, fall 2022 art fairs, spring 2023 art fairs, and fall 2023 art fairs yet to come.