Drawing Under Restraint

John Haberin New York City

Lina Bertucci, Matthew Barney, and Giosetta Fioroni

Does art still have a little fight left in it, beyond big business and mass entertainment? It may have to struggle first with chic images of contemporary artists, thanks to Lina Bertucci. Like Matthew Barney and Giosetta Fioroni, she sees art as about shooting stars, not excluding themselves.

The Morgan Library does not come lightly to contemporary art, much less to Hollywood. This is the institution turning in 2013 directly from Marcel Proust to "The Eucharist in Medieval Life and Art." Maybe something of the Eucharist survives in its drawings by Barney, titled "Subliming Vessel," as if they contained a god's blood. And when Fioroni turns to happenings, they have a silvery chic as well. Yet her drawings, like Barney's, struggle against the sublime, too. A related article looks at Barney's earlier videos, a performance that made Hollywood seem modest by comparison.

Stardust

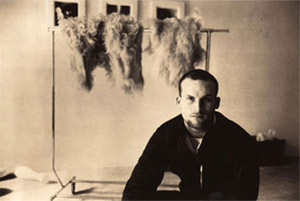

Lina Bertucci has not just an eye, but a nose, too. I mean a photographer's ability to set a scene, but also a nose for talent and celebrity, somewhere between a gossip columnist and a critic. Her portraits celebrate established and emerging artists from the last ten years, and she seems always to have found her subjects and their pose before the major magazines did. Her shadows give interiors an allusive, cinematic space that Cindy Sherman might envy. Yet even a beautiful, focused set of artist portraits raises questions about commerce and culture in an overhyped gallery scene.

Sometimes her props refer to an artist's work or personal life. John Cage has his chess set and calm intelligence, both in a tradition going back to Duchamp. Haim Steinbach poses as a weary space alien, undisturbed by two almost identical girls standing on his sofa as if floating on air. None has the polished look of an actor's promotional stills, as in work by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders or David Robbins. Still, when Elizabeth Peyton in short hair leans over her cigarette beneath striated film noir shadows, one has met an LA artist into stardom. Stepping back from the gorgeous wall display, one could well be watching it dissolve into a magazine spread.

Another media darling loves to pose for the camera, and it has led to videos of truly epic proportions. Matthew Barney really does mean less than meets the eye. But then with Barney so much meets the eye. His Cremaster Cycle might even throw in the kitchen sink at some point for all I know. His 2006 show—which filled Barbara Gladstone's plush, meandering space to the brim—disappointed many fans, but I see it as a piece with his career. When defenders use words like grandiose, hermetic, and self-involved as compliments, I start to distrust it much more.

The 2006 sculpture may even stand as his best work, starting with a scale that gives it a life after video of its own. It derives from his video collaboration with his wife, Bjork, but not simply as a fire sale on the props. The white plastic sculpture shows a whale hunt disintegrating before one's eyes, with rope spooling out across rooms and a ship's hull breached by its very contents. One could easily treat those expanding walls as a work by Richard Serra softened by a little petroleum jelly. Besides, if an artist has to take himself this seriously, he may as well chase the great white whale.

In fact, Barney takes himself awfully seriously, without a clear narrative or visual center, and his outsize ego seemingly feeds his own stardom. Perhaps art has come to emulate yet another marketing model, release on DVD. As neither mass entertainment nor a low-budget risk, Chelsea may stand to art's quieter and more adventurous pursuits much as Bjork does to indie. For all the glitter of big shows, thousands of light bulbs, and special advertising sections, perhaps only lesser-known artistic lights still know how to rock and roll.

A personal iconography

The Morgan Library's prints and drawings have served for comprehensive views of eighteenth-century France, Renaissance Venice, Dutch landscape even apart from Hercules Segers, the age of Rembrandt, Blake's Milton, and "Creating the Modern Stage." Its trip with Edgar Degas to "Miss La La" and the circus, so unlike Degas monoprints, already seemed transgressive—and dangerously close to the present. Fortunately, the Morgan has found an artist whose performances draw on Western art, Japanese rituals, offerings to Osiris, and the Egyptian symbol for stability. Never mind that Yale recruited that artist as a football player. He was a premed, not a bad way to learn human anatomy. And his project for nearly a decade now centers on a book called Ancient Evenings.

Of course, the book is by Norman Mailer, and the artist is Matthew Barney. The Morgan's seventy-five drawings, along with countless photos and magazine clippings, begin in 1988 when he was still a Yale undergraduate. Still, almost all date to the last decade and to River of Fundament, a project in tribute to such fellow obsessives as Mailer, the hunt for great whales, and General Douglas MacArthur. It only makes sense to start late, for he has already taken over an entire museum, the Guggenheim, for The Cremaster Cycle, the work that put him on the map. He has also appeared not so long ago as a charismatic emerging artist in "NYC 1993," at the New Museum, and for him 1993 proved quite a time. It was the moment before he began the eight-year, five-part, and 7½-hour video and performance epic that had him climbing a museum tower and bathing everything in sight in Vaseline.

Of course, the book is by Norman Mailer, and the artist is Matthew Barney. The Morgan's seventy-five drawings, along with countless photos and magazine clippings, begin in 1988 when he was still a Yale undergraduate. Still, almost all date to the last decade and to River of Fundament, a project in tribute to such fellow obsessives as Mailer, the hunt for great whales, and General Douglas MacArthur. It only makes sense to start late, for he has already taken over an entire museum, the Guggenheim, for The Cremaster Cycle, the work that put him on the map. He has also appeared not so long ago as a charismatic emerging artist in "NYC 1993," at the New Museum, and for him 1993 proved quite a time. It was the moment before he began the eight-year, five-part, and 7½-hour video and performance epic that had him climbing a museum tower and bathing everything in sight in Vaseline.

Now he has entered a bastion of rare books and manuscripts, but it takes guts to mention rare and Barney in the same sentence. If ideas are a creative artist's children, his is an art of no child left behind. Like Mailer, he keeps returning to men (always men) who think impulsively and big. He paints gold leaf on a copy of Ancient Evenings, like gilding the lily. He dismembers Hemingway paperbacks and sets out Leaves of Grass. He includes an iconic photograph of Mailer by Diane Arbus, and he must wish that early Diane Arbus were around to celebrate his idiosyncrasies, too.

Barney's current series unfolds in solo performances, and the Morgan devotes a room to what one must have looked like after the artist was done and gone. Drawing Restraint 20 took place at a steel plant, and that votive offering is chained to bound copies of Time headlined "The Case for Saving Detroit." In a project about ancient rivers, he must have loved that Ford's most famous plant, painted in 1932 by Charles Sheeler, was Rouge River. Barney had an early interest in Chrysler anyway, from the art deco of the Chrysler Building in New York. In drawings, he imagines approaching it by tunnel from across the East River. He imagines a man rising as if to meet it, surrounded by a gold circle like a sacred radiance.

Drawing Restraint refers to wall drawing, executed under restraint, with Barney bound to heavy weights—the colorful kind slipped onto barbells. It boasts of his athleticism in performance, like the muscle in his muscle cars, and it insists on how he needs restraint. To him, the effusion of his art is inseparable from his physical presence. He likes petroleum jelly, he writes, because works should appear "like they had just come out of me." And, he adds, as if they should be put back in. Now if only they were.

For all the indiscipline, he is building a personal iconography. It runs, of course, to solo figures, veils, and rivers, and it is surprisingly spare and traditional. Barney is a real draftsman, of the natural world and a post-industrial fantasy—and, with the help of lapis lazuli and red paper, a colorist. He also has a fondness for Velcro and thick frames, many (naturally enough) of the "self-lubricating plastic" used in cosmetic surgery. His clippings from art history run to others with darkly physical bravura, like Francisco de Goya even before Goya's Black Paintings, Domenico Tiepolo, Michelangelo, and Michelangelo drawings. Barney may be more like the subject that they mocked, but I guess he likes it that way.

An elegy for Pop

Giosetta Fioroni starts with abstraction and ends with a happening. Not a bad summary of a decade of art and culture, only her version unfolded in silver and in Italy. The Drawing Center even calls her retrospective "L'Argento." While her work also touches on Pop Art and Minimalism, Fioroni makes the styles all hers, thanks in no small part to aluminum enamel. That, a quiet sadness, and a sense of fashion. Italians, apparently, cannot even weep or carry on in the park without looking good.

That talent allows her to pursue her imagination without having to show off. Her work has plenty of room for white, with pencil or ink here, a wash of enamel or watercolor there. They hint at the countryside around Venice or Rome—or, more strikingly, a woman. Titles speak of the Tear on Her Face or a Beach Girl, but one would hardly know it. Emotional reticence is very much a part of her art and, for that matter, her presence as an artist. In a 1968 performance, she hired an actress to play her in her studio.

One in fact gets a glimpse of her as a shy but precocious child. Born in 1932, she is a bit old for a boomer, although the show's heart is the 1960s and 1970s. One can see her as early as 1941, sketching theaters for her father's puppet shows. Display cases also contain artist books in collaboration with her significant other, a poet, and they still evoke a child's active imagination—in images of spirits, a sorceress, heart, house, and home. She also created a doll's house in 1969, with a peephole for the diorama of animals. She called the photos of an actress in her studio The Spy Hole.

If anything, her art becomes sparer while reaching for the sublime, with her landscapes as little more than a trace of silver, like the incomplete geometry of Robert Motherwell. She had a home by then near Venice, and the Center's small rear gallery, its "drawing room," shows what the catalog to her 1971 show called "defining through absence." Still, she made her name in Rome, as part of the Scuola di Piazza del Popolo, a movement named for the square where it gathered for coffee—and where Caravaggio, in a church there as well as with his Madonna di Loreto near the Piazza Navona, invented the Baroque. I recognized only one name, Jannis Kounellis for his coal and rails. Like Fioroni, the Scuola looked for inspiration to both the land and the media. But then Giuseppe Penone and the more famous Arte Povera approached its anti-art with a studied Italian elegance as well.

The show begins with three abstractions from around 1960, in which thin touches of geometry frame a texture of metal, paint, and sand. Think of early Helen Frankenthaler in silver. Small text here and there, as with Jasper Johns or Robert Rauschenberg, anticipates the turn to Pop Art but also to a greater emptiness. Downstairs, in the museum's basement "lab," the show comes to a fitting conclusion with three films from 1967. In one, handsome young people smoke, peer into the bushes, draw on another's torso, or shave another's face and chest hair. In another, couples kiss, put on make-up, dress, and undress. Both are awfully stagy for a happening, like puppet theater, but then so was the summer of love and the 1960s.

In between, the main gallery has the vitrines and the subject of her third film, a woman's eyes, nose, lips, and the silhouette of hair or a hand. The quick brushwork and sharp contrasts point to a source in fashion photography and Italian cinema—and a parallel in Andy Warhol. Yet where his silkscreens depict fame, death, and disaster, hers stick to anonymity and quiet tears. Does Fioroni assert a woman's prerogative to picture herself, demand what one critic called a "fidelity to sight," approach a bleaker Minimalism or a haunting beauty, or refuse the construction of meaning altogether? The Center wants to have it all, and its contradictions bear on both the limits of her art and its attractiveness. She offers less the dark underside of culture than its elegy.

Lina Bertucci ran through February 18, 2006, at Perry Rubenstein, Matthew Barney at Barbara Gladstone through May 13. Subliming Vessel: The Drawings of Matthew Barney" ran at The Morgan Library through September 2, 2013, "Degas, Miss La La, and the Cirque Fernando" through May 12, and Giosetta Fioroni at Drawing Center through June 2. A related article looks at Matthew Barney's "Cremaster Cycle" at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in 2003.