The Year in Quotes

John Haberin New York City

NYC 1993 at the New Museum

So what does the New Museum see when it looks back to the year 1993? Why, everyone was doing it!

Now everybody—

Everyone was ironic. Everyone was naked. Everyone was angry. Everyone was afraid.

Everyone was unflinching. Everyone was unraveling. Everyone was in solidarity. Everyone was alone.

Everyone was in the South Bronx. Everyone was downtown. Everyone was in the clubs, until the cops shut them down.

Everyone was demanding sexually x-plicit women. Everyone was commanding to shut pornography down.

Everyone was graduating Yale or Goldsmiths. Everyone was dying, mostly of AIDS.

Silence was death. Painting was dead. Drawing was garbage. Trash was art.

Art was camp. Art was a prison. Art was a cult classic coming to be.

The Biennial was political. The Biennial was a scandal. P.S. 1 was independent. Exit Art was alive.

Artists were pathfinders. Artists were coke dealers. Artists were celebrities, on a fringe of their own.

Someone else had a gallery. No one had the Internet. Everyone had a camera, but mostly a toy.

I did have my penis. What's love got to do with it? I can't imagine ever wanting to be white.

Everything's connected to a Times Square donut shop. I have been certified as mildly insane.

I'm at DIA. I'm desperate. I'm in bed. I'm at the morgue. I enjoyed your show. So this is what you want.

The year in quotes

All right, maybe not what you or I want, but it is "NYC 1993: Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star" at the New Museum. Think of it as "1993" in quotes, as indeed exhibition titles require, with Sonic Youth on hand to supply the subtitle. It shows artists yearning to live in quotes and yet to live forever in the present. With Devon Dikeou's lobby directory boards, the show recalls some steamy spaces for art, like Flamingo East or hotels in the 20s. With Andrea Fraser's audio tour and signage, it recalls when Whitney Biennials still had curators like Thelma Golden, Lisa Phillips, and Elisabeth Sussman, with the power to scandalize or to shock. With Lina Bertucci photographs, it recalls when artists were conscious of their glamour but not necessarily breaking even.

It is a side of 1993 that the museum has every right to remember, since it was among the players that helped to create it. It was then an alternative space in Soho, as was Exit Art—and their founders were both alive. Just to say so points to something that art has lost. Twenty years later, a new New Museum fills five floors of its oversize boxes on the trendy Lower East Side. It also goes about a museum's business of popularizing, while boasting of the time as uncommercial. Can just twenty years now turn the past into art history?

It is a side of 1993 that the museum has every right to remember, since it was among the players that helped to create it. It was then an alternative space in Soho, as was Exit Art—and their founders were both alive. Just to say so points to something that art has lost. Twenty years later, a new New Museum fills five floors of its oversize boxes on the trendy Lower East Side. It also goes about a museum's business of popularizing, while boasting of the time as uncommercial. Can just twenty years now turn the past into art history?

"NYC 1993" hopes to celebrate a time when art had urgency and direction. Frustrating, politically correct, and insufferably trendy, much of it has proved all too easy to forget. And then it refuses to die, like cockroaches back then on Broadway. I truly enjoyed it, although "I enjoyed your show" is a quote, too—from a print by Coco Fusco that enters a cluttered plea for The Undiscovered Amerindians. (Start in on the quotes, and they never seem to end.) It is one-sided all the same.

How one-sided? If sex and death are not your thing, your only thing, this is not for you. I should know, because I had been been around myself, and I started writing that very year—and in fact I have recycled images of work by the same artists from past reviews rather than new press images. This was not "before the Internet," although Wolfgang Staehle wanted to believe otherwise with his BBS log-in screen. I was online, and I started this Web site within a year or two. Pioneers like Paula Cooper had left for Chelsea by 1997. Back in the day (the same year that Arthur C. Danto started writing so brilliantly for The Nation), I found another side or two.

It had room for painting and sculpture. Mark Tansey was reveling in irony, but not about sex and death. It had its versions of European art and Minimalism, like that of Rosemarie Trockel—who just had a retrospective at the New Museum. It had new media, when that meant a penetrating experiment for Gary Hill rather than Alex Bag's self-portrait patterned after an extended TV ad. It still had the "Pictures generation" with their own laden irony, like Barbara Kruger and Jenny Holzer. Apparently, American politics could point in more than one radical direction.

It had other sides to some of the very artists in "NYC 1993." The New Museum showed some not long ago, with a look at East Village art of the 1980s. Among others, Cindy Sherman reinvented herself so often that it is hard to believe that she had her Sex Pictures in precisely 1993, but she did. Zoe Leonard, too, did not only photograph anatomical models and chastity belts, and elsewhere she turned junk into an entire ecosystem. Maybe Sue Williams was not going to renounce her hatred of porn, not even when other women were happily exploiting it. Still, within three years Peter Schjeldahl was thanking her for finally discovering art.

The artist in squalor

Not sure whether to trust me? I know, I was too caught up in abstract painting "after the fall." You might have your own memories of squalor, like the haunted city of Martha Diamond. The AIDS crisis was altogether real, as for Nan Goldin, Alvin Baltrop, Félix González-Torres, and Martin Wong, although Ed Koch had left office, New York had a black mayor, and welfare hotels were at last shutting down. The Young British Artists were young, but "NYC 1993" finds sincerity and political sexuality awareness in them as well. Gillian Wearing protests against a serious recession, Andres Serrano photographs AIDS-related death rather than his struggles with piss and Christianity, and (thankfully) Chris Ofili or Damien Hirst does not appear at all.

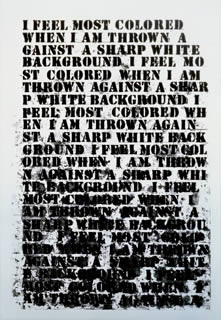

"Blues for Smoke" at the Whitney looks at the same decade, again with many of the same artists. There Glenn Ligon, who indeed had advised on art from avant-garde music and on "Blues for Smoke," focuses on Richard Pryor jokes rather than images that offended Pat Robertson. Rachel Harrison tosses off celebrity sketches rather than a tower of garbage like a blood-stained Statue of Liberty. Renée Green considers the assimilation of black culture rather than "the meaning of travel." David Hammons thinks of jazz rather than the shape below a hoodie, Julia Koettha of the blues rather than an Antibody, Kerry James Marshall of an angel rather than frustrated desires, and Lorna Simpson of a family album rather than the thickness of lips. Does the New Museum look at race and see only naked black bodies?

"NYC 1993" pays a real price for that kind of looking. It can lead to trivia, as when Kathe Burkhart obsesses over Liz Taylor and Lutz Bacher over William Kennedy Smith. (Remember him? I thought not, but his rape confession included "I did have my penis.") It tends to piety, as with a standing Virgin Mary by Kiki Smith. It is all but bereft of humor, even when Rudolf Stingel carpets the fourth floor or Andrea Zittel supplies rugs for the cafeteria.

That kind of looking also gets awfully self-involved. Sean Landers fills hundreds of sheets with his impression of "tits," "shit," and how he exposed himself. ("Am I too hard on myself?") Sadie Benning turns her toy camera on others, but "I wanted to feel sorry for myself." Above all, there is a single dimension to their protests, as when Marlene McCarty responds to the first Gulf War solely by remembering a soldier as a gay victim of hate crimes. Rirkrit Tiravanija was already dishing out food, a performance he has restaged again and again and again.

Like it or not, though, all this was a dimension of 1993, and it has not gone away. People really were dying of AIDS (although Hannah Wilke was dying that January of lymphoma), and sexuality is still on the agenda. The prison of Neo-Geo had taken hold of museums, like the prison bars from Robert Gober. Neoclassical self-portrait busts by Janine Antoni, licked and washed in soap and chocolate, would fit just fine with show after show of Dieter Roth now. Maybe the most deplorable side of 1993 has had the most lasting impact. Matthew Barney, Paul McCarthy, Jason Rhodes, Charles Ray, and a simulated crime scene by Pepón Osorio all anticipate twenty years of overblown installations. Gabriel Orozco had begun categorizing and collecting, while Nari Ward packed a space with beat-up strollers.

Like it or not, though, all this was a dimension of 1993, and it has not gone away. People really were dying of AIDS (although Hannah Wilke was dying that January of lymphoma), and sexuality is still on the agenda. The prison of Neo-Geo had taken hold of museums, like the prison bars from Robert Gober. Neoclassical self-portrait busts by Janine Antoni, licked and washed in soap and chocolate, would fit just fine with show after show of Dieter Roth now. Maybe the most deplorable side of 1993 has had the most lasting impact. Matthew Barney, Paul McCarthy, Jason Rhodes, Charles Ray, and a simulated crime scene by Pepón Osorio all anticipate twenty years of overblown installations. Gabriel Orozco had begun categorizing and collecting, while Nari Ward packed a space with beat-up strollers.

At least they were doing it before trash art became synonymous with wealth. Something has changed in twenty years, and the curators do their job of documenting it. In a pretend TV guide, Massimiliano Gioni, Gary Carrion-Murayari, Jenny Moore, and Margot Norton supply a chronology of political and media events. Wall labels often note the original venue, and dealers, too, have grown wealthier in twenty years. David Zwirner then could still tackle "sexually x-plicit art by women," Gavin Brown could work out of a room in the Chelsea Hotel, and one had to ask for the key. No, not everyone was doing it, but one has to wonder for those doing it on the cheap ever since.

"NYC 1993: Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star" ran at the New Museum through May 26, 2013. "Now everybody—" quotes the ending of Gravity's Rainbow, Thomas Pynchon's 1973 novel that ushered in a surprisingly brief, problematic, and altogether necessary Postmodernism. This show wants to take you there. I should explain that, while my opening riff increasingly quotes selected work in the exhibition, I am responsible for much of it. The images from past reviews are of artists in the show, but only Charles Ray with the same work.