Selling the Store

John Haberin New York City

The Fate of the Rose Museum

Hernan Bas: A Collector in Brooklyn

It takes more courage than ever to make art—or maybe chutzpah. Will hard times purge galleries of hype and celebrity or of risk and experiment? Maybe both, but one thing for sure: only an idiot would pick this moment to dump six thousand works of contemporary art.

Who is minding the store?

That is just what Brandeis University plans to do. On January 26, 2009, its trustees voted to close the Rose Art Museum, founded in 1961. They decided to put the collection up for sale, what museums call deaccession, to cover operating expenses. Meanwhile the Brooklyn Museum does quite the opposite: rather than betray a donor, it has turned its exhibition space over to one, no strings attached. And the donor shows off a single artist barely in his thirties, Hernan Bas.

Did Brandeis consider how museums over the centuries have slowly taken over the role of great patrons, while also catering to collectors? Did it ask how changing financial stratagems are shaping contemporary art? If not, it has good company. While Brandeis's failure shows the importance of community outreach and cooperation with potential donors, the Brooklyn Museum shows its excess. Together, they make a chilling study in patronage for modern and contemporary art.

Other recent articles take up deaccession at the National Academy, the role of a donor in saving LA MOCA, the Emily Fisher Landau Center as a museum in waiting, and the Met's salute to all that money can buy. Meanwhile museum plaster casts, compared to originals for sale, suggest how collections first became museums. Related articles also tackle two model museums based on private collections—in loans from the Norton Simon at the Frick—and museums that cater to the Nasher, Wagner, and Broida collections. Last, the 2009 art fairs show what happens to traffic in art in a bad economy. When collectors and art advisors play it safe, safer artists and institutions benefit.

All these stories raise questions about the integrity of all art institutions. Can museums ever separate themselves from their origins of museums in private collections? Should they?

How do public and private collections shape contemporary art? How will that in turn shape change in a troubled economy? Does the experience of art share more with learning or sheer pleasure? Can one even tell the difference? Does it matter which institution is teaching and which community is learning?

In each case, the collision of public and private interests distorts art, but also makes art possible. Worst of all, there is no happy medium. All one can do is look as often as one can at how people value art. Brandeis and Brooklyn alike see both as means to institutional ends. Consider each in turn.

The no museum

Many colleges face badly depleted endowments these days, and Brandeis reports a $10 million shortfall. Does that make the Rose Museum look awfully tempting? Christie's estimates the collection as worth up to $400 million on a good day, but an ongoing financial meltdown is not a good day. As if to bring the point home, the university had invested in Bernard Madoff's Ponzi scheme, and the trustee vote to close was unanimous. Herd mentality, anyone?

Real and imagined crises always put ethical issues in focus, which is why intro philosophy classes (and defenders of torture) like them so much. The National Academy Museum, with its own fiscal crisis even before the Great Recession, came under fire for selling just two paintings, by F. E. Church and Sanford Robinson Gifford. Brandeis multiplies the scandal by three thousand—or does it? The university might reply that the Academy is betraying its mission, while Brandeis is returning to what it does. It would be wrong.

The distinction puts in focus what one means by an art institution's mission—and how money has a way of molding it. The Academy, too, is also a school. Somehow, a collection open both to students and museum-goers does not seem all that useless. In opening a museum and accepting gifts to fill it, Brandeis accepted a mission involving other parties, too. It undertook obligations to donors, the university community, and the public.

Within a day of the vote, the Massachusetts attorney general's office announced an investigation. The legal questions concern the terms of gifts, as specified in wills and agreements with donors and estates, and the state's power over the actions of nonprofit institutions. They also turn on the distinction between selling off individual works, probably a breach of contract, and eliminating the museum altogether. Who can blame a museum for selling art, Brandeis reasoned, if there is no museum?

I cannot pass on the legal issues, on the performance of Michael Rush as museum director, or even on the collection. Most likely, I shall never see it in person before it scatters to the four winds. (Its best-known Robert Rauschenberg did look rather nice at the Met, along with other combine paintings and Rauschenberg collaborations.) I also cannot predict the story's ending. In no time, the university administration was backtracking—or at least hedging.

One can, however, see again how corporate practices ignore the public good. One can see, too, how these practices shape institutions and how institutions, in turn, shape art. No one seems to remember that Brandeis last raised hackles in 1991. It then sold fourteen works, including three by Pierre-Auguste Renoir—not, it insisted, to cover operating expenses, but to focus the museum on American art and to make it financially independent. Apparently it succeeded a little too well.

Rose is a rose is a rose

In no time, the thought that anyone might defend Brandeis sounded silly. Within a week of the announcement, at least a dozen articles commented on the move, and not one was less than devastating. Roberta Smith, in The New York Times, singled out the slippery reasoning that could let Brandeis sell art, but not formally deaccession it. Ordinary curatorial guidelines bar selling work in a permanent collection to meet an annual budget, if at all. On March 16, in an angry letter, fifty members of the Rose family called it "plundering."

Other museums received some notorious press at year's end for something akin to downsizing. LA MOCA lost its director, who it claimed had overspent on exhibitions. Still, they faced fewer complaints. Perhaps the donor who crafted the deal at MOCA is its savior. Perhaps the National Academy will right itself after just the two sales. MOCA's ex-director has already landed on his feet.

Brandeis, by contrast, confuses its savior with the resource it is giving up. The more Brandeis tries to detach itself from its museum, the more it looks like an art museum at odds with art. No wonder its conduct looks suspicious. It echoes MOCA's institutional mismanagement, only without a happy ending. It also stirs suspicions that MOCA may not have a happy ending after all. In one case the donor dictates terms, and in the other case the donor gets the short end of the stick, but both are cases of selling out.

Why less anger directed at MOCA or the National Academy? For one thing, people in the arts are less likely to criticize one of their own. To put it more generously and, I think, more validly, people in the arts care about art. For another, no one has seen anything like this plan. It is hard to imagine thousand of works suddenly entering the market, finding buyers, and fading from sight. It is hard to imagine what the university will do if, as is likely, plenty of work does not find buyers at a good price.

All this criticism has run into a backlash of its own. At least some students and faculty want to do anything it takes to keep the university solvent. Brandeis needs teachers, students, scholarships, libraries, and classrooms, or it is hardly a university. Is a museum as necessary? Letters to The New York Times derided Smith for privileging art over real life.

As of Memorial Day 2009, one cannot say which backlash will win out. Brandeis has hedged on the question of how many works will go to auction. It has hedged, too, on whether the museum will survive the changes and what survival will mean. After a renovation, the Rose may reopen as an exhibition gallery, but also as a "fine arts teaching center." Has the administration backed off from the trustee's vote—or just put a nicer face on it?

Art and other communities

Defenses of the sale leave a sour taste. When it comes down it, they do not really address the university's legal or financial responsibilities. They do not even address whether the plan can help the university survive. They translate into this: we must do something, and never mind what. Again as with torture, leaders can always turn a crisis to their own ends—or manufacture a crisis as needed.

Defenses also beg the question of the place of art in a university or elsewhere. As Oscar Wilde said, all art is quite useless. So, though, is a liberal arts education. That is why they both are so effective at developing thought and feelings. Art has direct educational benefits, too, at least for the art and art history departments, but also for history or literature classes that put more and more stress on cultural context. And a museum also contributes to a university's prestige—encouraging more college applications, more faculty hires, and more support from the wider community.

Suppose, though, that the university has no business in the museum business. Objections to museum deaccession still apply. What will potential donors think? Those who gave to the Rose Art Museum and wish to support the university could equally have purchased art for themselves. They could then have loaned it to Brandeis, sold it in the boom years, turned over what a sale will obtain today, pocketed the rest, and endured the outcry.

I would think twice now about contributing toward a center for research, such as the Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics at my alma mater. What if Princeton decided to get out of that field in search of a little pocket money? And what if it were mismanaging finances while making the decision?

The action is financially irresponsible, a betrayal of trust, and a blow against the arts. It is also just plain crazy, unless you think that a university needs money only this once. Presumably, Brandeis does not have lots of other museums hiding somewhere as future cash cows. Besides, another prominent institution, the United States government, is talking about the need to invest in infrastructure in a crisis.

One wonders if the university even gave a thought to what it will do. Did it give a thought, too, to how a glass-covered museum can function as an "exhibition and learning center" rather than a mausoleum? Did it give any thought, like MOCA, to alternative schemes? Could it have moved the artwork or management of the museum largely intact into the hands of a nominal partner? At Brooklyn, unfortunately, a partner seems hovering already in the wings.

The tower treasure

First came the midcareer retrospective. Now, with Hernan Bas, comes the mid-market survey. Is the suffering Brooklyn Museum having a midlife crisis?

It had to happen. Museum status for early stardom and midcareer shows fit with the boom years before 2009. If you had not yet fawned over John Currin, Lisa Yuskavage, or Elizabeth Peyton, you got your chance. A downturn, however, requires stronger—or maybe weaker—measures. Bas's small paintings struggle to occupy just half the upstairs gallery for special exhibitions. And they come cheap, dirt cheap. The 31-year-old Miami artist's work comes courtesy of a single Miami collection, the private museum of Don and Mera Rubell.

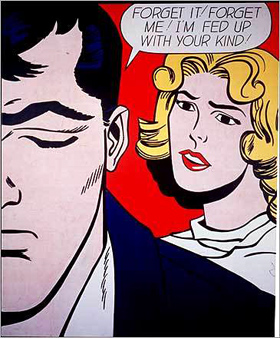

Bas wants them to look chintzy, too, like Karen Kilimnik without her feminism or appropriations. One could call him the gay Peyton, with his slapdash portraits of eternal youth, downcast eyes, rosy lips and cheeks, and poses out of celebrity magazines. His boneless, half-dressed males loll in oceans, gardens, and interiors, like the Hardy Boys with lipstick and under sedation.  To round out their forlorn idyll, the video silhouette of a sailing ship bobs in a tempest and a mermaid swims across five projections, like Bill Viola with flippers. Along with the accompanying debris, Bas adds a freestanding sculpture, a jewel-encrusted shield inspired by the fin-de siècle esthete in J. K. Huysmans's Against Nature. I may never use the words languorous and decadent in a sentence again.

To round out their forlorn idyll, the video silhouette of a sailing ship bobs in a tempest and a mermaid swims across five projections, like Bill Viola with flippers. Along with the accompanying debris, Bas adds a freestanding sculpture, a jewel-encrusted shield inspired by the fin-de siècle esthete in J. K. Huysmans's Against Nature. I may never use the words languorous and decadent in a sentence again.

Straight, dead white guys get more than their share of exhibitions, just not on Eastern Parkway. Since "Open House" celebrated borough artists in 2004, the remodeled museum has made room for Jean-Michel Basquiat, kids' graffiti, "Global Feminisms," contemporary Caribbean artists (if not Frank Walter(, ©MURAKAMI, Gilbert & George, and a painting in the lobby by Kehinde Wiley. Downstairs Timothy Greenfield-Sanders and Elvis Mitchell have brought slick camera work to well-known African Americans. If you ever wanted to see Al Sharpton in a fashion shoot, you had through March. Either way, the museum leaves nothing to chance, like a class trip with a very determined teacher. A wall label asked how race has entered your life.

I have no patience with conservative criticism of political correctness. In practice, it means only that someone has disrupted expectations. I just want them to be adult expectations. Instead, the museum aims only at grade-school education. That need not, however, mean an innocent eye. With Bas, a public institution allows Rubell shameless self-promotion, all for the cost of shipping and hanging a few dozen works. He and the artist's dealer, Lehmann Maupin, must be tracking their net worth every step of the way—just in time for a show of larger work downtown that buries the young actors in a more crowded and shapeless idyll.

Museums have emerged from private collections, and their institutional and financial pressures still shape art. As money grows scarce and as art fairs grow anxious or "Independent," the pressures only increase. Still, even when the Met, the Guggenheim, and the Modern have ceded space to collectors, they clearly wanted the art. When museums have exhibited emerging artists, the group shows have promoted discoveries and diversity. And at some point they, too, become pandering, like the Jewish Museum with Leonard Cohen. The Brooklyn Museum is way past that point.

Hernan Bas ran at The Brooklyn Museum through May 24, 2009, and at Lehmann Maupin on the Lower East Side through July 10.