Naughty Bits

John Haberin New York City

Bill Henson and Nathalie Djurberg

Judith Eisler and Cecily Brown

My, artists are getting naughty. Like most Americans, they also prefer sex to sacrilege. What, a book by W. J. T. Mitchell asks, do pictures want? These pictures want to impress, to puzzle, and to shock.

Bill Henson and Nathalie Djurberg bring darkly comic views of sex, drugs, and rock 'n' roll—only without the drugs and the rock. Judith Eisler gets hers on more elusively, in a kind of film noir in living color. Last, Cecily Brown supplies the soundtrack, right out of Jimi Hendrix, along with a cornucopia of temptations out of art history.  They can even approach abstraction. Maybe all these pictures want to come over and hang out, too. And maybe so will you.

They can even approach abstraction. Maybe all these pictures want to come over and hang out, too. And maybe so will you.

Earth and clay

Sacrilege is so yesterday. It went out back when Chris Ofili entered the collection of the Museum of Modern Art and Andres Serrano prepared to abandon his piss Christ for something browner. Now artists get their kicks whatever they do. They get them even when they tackle global politics, as at the Whitney Biennial. They get them when they set aside the pills that so fascinate Fred Tomaselli, so as to question images of sexual transgression. They had better.

Bill Henson comes all the way from Australia, where I can only imagine the transgressions. And he brings with him a dark vision. A woman poses erect or on the ground, pressed close to the picture plane against an indecipherable background. Other figures lurk in forests, made eerier by the lone touch of sky. Nothing marks them as erotic beyond the fire raging in one photograph—unless one counts the dialectic of touchable and hidden, rage and sky, vulnerable and vanishing into that nothing. The nearly six-foot prints, like the characters themselves, soak up color from the shadows.

They share the staging and scale of Jeff Wall, but without his light boxes or pretense of storytelling. A highway underpass could come right out of one of Wall's photographs. They also avoid the self-conscious artifice of Deborah Mesa-Pelly or Hanna Liden, who takes her goth fantasies more seriously than she may care to admit. Henson's elegance and lack of irony may make him sentimental by comparison, but he pulled me in and scared me away. Do the fleshy cheeks, vulnerable eyes, and look of film stills blown way too large update Cindy Sherman? A glossier art market has its own transgressions.

If mystery mined for beauty turns you off, Jocelyn Hobbie's paintings makes things explicit. A nun poses naked from the belly up, a painter's model awaits a spanking, and a dozen others expose their preposterously pointed breasts. As a woman milking a repertoire straight out of Francis Bacon and Pablo Picasso, Hobbie asks whose gaze turns on whom. Many of her models indulge in art, even if that means carving vaguely "primitive" patterns in wood. In "Idols of Perversity" at the same gallery last year, I succumbed to idol worship myself. Here the obvious patterns and garish colors approach condescension.

Nathalie Djurberg ups the ante still further, to porn flicks in claymation. Never has plasticine indulged in so much sodomy in so short a time. The stop-action recalls Nan Goldin and her haunting slide show of love and death. Djurberg, who works in Berlin, takes equal pleasure in the video's choppy movement and her cast's virtuosity at slipping in and out of something comfortable. Her slick soundtrack plays against the clumsy, scrawled dialogue—which appears within thought balloons at the pace of actual handwriting, in block capitals. I found myself wandering from monitor to monitor, less to take it all in than to join the leisurely carnival.

Instead of what Bruno Bettelheim called the uses of enchantment, I thought of Mary Gaitskill savoring a Chelsea opening for her next novel. The videos, of perhaps three to five minutes each, involve a cartoon tiger, little girls, a mother bear, a mustachioed gentleman, poison apples, and other stock figures. Call them "Fractured Fairy Tales," after Rocky and Bullwinkle, for an age of Madonna, Matthew Barney, and Julie Blackmon. Still, the plots take perverse and ingenious turns. The woman who slices off a man's legs and head leaps all over him, an innocent little girl taunts and glowers at everyone in sight, and the raging bear puts on an apron and rocks the child to sleep. Djurberg may never probe your fears or fantasies, but you can still enjoy every minute.

Let it all hang out

Lives and desires always hover around art. For Judith Eisler, they appear as close as the acid red light that bathes a character from behind and as elusive as her blurry compositions can make them. They let down their long, flaming hair and breathe in the smoky indoor air while talking on the telephone—the old-fashioned kind with a handset and spiral cord. They expose their flesh and lower their bodies underwater. Her close-ups ensure that their bodies remain near the picture plane while their heads get cut off. As for what has stained those panties, she hesitates to say, and so shall I.

If the imagery seems not quite ready for prime time, Eisler begins with stills straight off the tube. From there, she paints smoothly and thinly enough that the weave of her canvas still shows.  The exhibition title, "Rapt," puns on "rapped" and "wrapped." It evokes heightened states of consciousness, pop culture, and the danger of suffocation or a thorough beating. Call this Gerhard Richter and Richter's late work meet film noir, the Lower East Side, and daytime television. Expect a crowded party.

The exhibition title, "Rapt," puns on "rapped" and "wrapped." It evokes heightened states of consciousness, pop culture, and the danger of suffocation or a thorough beating. Call this Gerhard Richter and Richter's late work meet film noir, the Lower East Side, and daytime television. Expect a crowded party.

Does this sound like painting conceived in a postmodern focus group? It hits all the right notes, preferably on electric guitar. Without the artistic, political, and personal reference in an actual Richter, elusiveness runs the risk of avoidance. Yet anyone can become caught up in Eisler's technique, her echoes, and her threats. Think of Marilyn Minter in her studies of disgust and desire. Here, too, photorealism can trick you into stepping back in the hope that it will all come into focus.

Another show suggests how that focus group pulls off a consensus. "The Trace of a Trace of a Trace" has just one work each by ten artists, including Richter at his murkiest. The selection plays it safe, but it hangs together well. It includes Jack Goldstein's fireworks against an enigmatic city in silhouette, Vija Celmins with her galactic points of light, and Enoc Perez's solarized cliff dwelling. It includes, too, Mary Weatherford's hazy Crystal Shores of You. The exhibition title alone is staggering.

The artists make Eisler a model of clarity by comparison. With Eberhard Havekost, the blur of an automobile hood echoes Mark Rothko. And with Angelina Gualdoni, Memory Glides Forward (The Future Precedes the Past). (Hey, it can happen.) The subject, a loft-like space under construction, takes on the context of a contemporary city. It gets at what happens when art translates visual data into landscape. It suggests, too, the making or display of art.

So do the framing crossed staircases and the perspective grid of insulating ceiling panels. Icy colors give them the appearance of reflective glass, and a brushy foreground seems about to engulf the interior. Work like this echoes the Romantic sublime. So could Eisler's "Rapt," but without the icebergs. Together, these shows suggest how Romanticism still colors art's steamiest fantasies. A G-rated audience can respond, too.

Are you experienced?

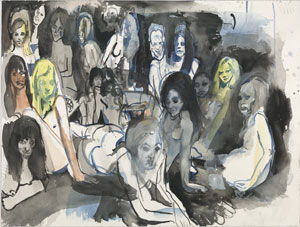

Jimi Hendrix hated the cover of Electric Ladyland. He had asked for something more innocent than electric—children climbing on Central Park's sculpture after Alice in Wonderland, much as I had as a child but in a photograph by Linda Eastman. Instead, he got a more adult kind of play. The photo for the album's British release, by David Montgomery, shows nineteen naked women facing front and on the ground, against a black background that sets them at a dark remove however close they come. An American like me might not recognize that Ladyland, but Cecily Brown would, as a Young British Artist before her move to America. She makes it part of her very adult drawings as well.

She calls the show "Rehearsal," a term that Hendrix would appreciate, but she refers, the Center insists, to an old French word, rehercier. It means "to go over something again with the aim of more fully understanding it." Are you experienced? Apparently, she is—not just with classic rock and postmodern arcana, but also with art history, evident in Brown in retrospective at the Met. She lets children back in the game, too, along with the themes of Bestiary and Ladyland. Together, they describe domestic life as a theater of cruelty.

Children cavort no end in a drawing room after William Hogarth. Adults barely removed from children or animals torment and seduce one another as well—in scenes of carnival and Lent after Pieter Bruegel, Saint Anthony after Hieronymus Bosch, and Adam and Eve in a crowded, lusty paradise. Even nudes after Edgar Degas fit with copies of the album cover. Brown may leave the center of the action incomplete, for a greater sense of motion. The white also suggests postmodernism's obsession with ambiguity, repetition, and erasure. This artist refuses to censor anyone but herself.

Brown approaches the past with skill and understanding, in ink as well as watercolor and pastel. Larger sheets allow more white space and more slashing attacks. They move most easily between abstraction and representation, much like her paintings. They may provide clues to how she got to her paintings, with their hints of Pablo Picasso and Willem de Kooning—or they may show her confident enough now to take her appropriations back in time. Like those of Elizabeth Glaessner abd Jordan Kasey, they also keep circling back to women. They are still what a title calls her Jeu de Dammes Cruelles.

Olga Chernysheva made it to New York, too, but only for a month. The Drawing Center invited her all the way from Russia, in return for her take on the city in charcoal. New Yorkers take pleasure in hating tourists—and not only at home. Even when I travel, I want to know neighborhoods and museums like a native, and I want to keep walking, without crowding the sidewalk. Chernysheva hates to play tourist, too, but she is also never at home. As one title puts it, she is Disappearing into Nowhere.

She applies her polished renderings to fragments of the city on the move—a blow dryer in one of those rare New York restrooms, a fire hydrant with its protective bollard bent out of shape, the back of heads, legs with only their shadows, or her illegible reflection in a surveillance mirror. Shoes behind glass seem desperately to need a home. She often adds a title on a thin slip of paper, pasted as if it, too, barely belongs. Text describes the scenes as Before the Start, Empty and Full, Distant and Near. A man lurks at the edge of a busy playground, but Chernysheva is lurking, too, on this side of the fence.

Bill Henson ran at Robert Miller through June 3, 2006, Hanna Liden at Rivington Arms through May 14, Jocelyn Hobbie at Bellwether through May 6, Nathalie Djurberg at Zach Feuer through May 27, Judith Eisler at Cohan and Leslie through March 25, and "The Trace of a Trace of a Trace" at Perry Rubenstein through April 15. Cecily Brown and Olga Chernysheva ran at the Drawing Center through December 18, 2016. A related review discusses Brown in painting.