What Hysterical Women Say

John Haberin New York City

Mika Rottenberg and Karen Yasinsky

Marshal Pels and Zoe Beloff

If feminism flourished after the 1960s, it was not just politics. Feminism meant playing against stereotype, and so did art. In 1972, the year that the Democrats added the Equal Rights Amendment to its party platform, art still mostly looked like a blank wall—the wall of color-field painting or Minimalist sculpture. However, the walls were beginning to crumble. Earthworks were dissolving, and irony was creeping in.

Still, no question that they crumbled faster for women. One could almost say that men liked irony because they could play to stereotype, while women could see stereotypes as confining. They still do. Recent shows have women not so much breaking out of character as struggling for the right to play grown-up artists. They may still act like nuts and sluts,  but at least they can call the roles painfully confining. As one says her mother tells her, "you have a fertile imagination, and I suggest you confine it to your sculpture."

but at least they can call the roles painfully confining. As one says her mother tells her, "you have a fertile imagination, and I suggest you confine it to your sculpture."

Mika Rottenberg plays fashionista, but her bare limbs still have to punch their way out of a small box. Karen Yasinsky learns from French film the lesson of patience. She and Nathalie Djurberg need it to endure a fairy-tale childhood. As for Marsha Pels and her mother, she and Zoe Beloff act out studies in hysteria. I could easily have included a recent show of black women and their stereotypes, "The Brand New Heavies," although they are just a bit more "in your face." I could also have included the latest from Cindy Sherman and Carolee Schneemann, but they deserve a space all her own.

That letter from a mother recalls Freud's idea of hysteria. It has not held up well, and Freud, too, abandoned it. Still, against all odds and many a sense of justice, it lived on. As William Butler Yeats wrote, "I have heard that hysterical women say / They are sick of the palette and fiddle bow." These women are not in the least sick of art, and they have other things to say. Besides, if an artist cannot be neurotic, honestly who can?

Blessed are the cheesemakers

In the decades after the 1960s, artists did much to tackle stereotypes, but women more than men. No doubt they had to do more. Whose identity and power was more at risk? While men were loosening up abstraction on a larger and larger scale, Lynda Benglis was letting it ooze onto the floor. While Richard Prince was glorying in his own satire of the Marlboro man, Laurie Simmons in her East Village art days could barely stand a camera on a doll's legs. In a way, Mika Rottenberg turns Sherman's subversion of film stills and fashion into a more dangerous high style.

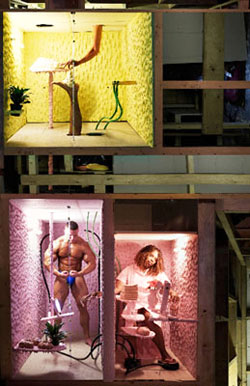

Rottenberg makes an unlikely candidate for a fashionista. So do her heroines. In her last show, as also in the 2008 Whitney Biennial, they looked closer to sumo wrestlers, collective farmers, and torturers. In the sweaty confines of cramped, connected spaces, they progressively molded something soft, like an assembly line for rancid cheese. The Guggenheim included her video in "The Shape of Spaces," but she had squeezed the space out of its shape. Shifting her focus from New York to a factory in China, she has kept squeezing.

Now fashion has come to her. W Magazine, hardly a stranger to irony or access, has sponsored seven large photographs. They look all but incomprehensible apart from her video. Why is that bodybuilder crouching? Why are all those limbs sticking out through holes in the wall, and how do so many tiny chambers fit together? And speaking of fashion, what is that young black woman fashioning? Would she be glad you asked?

Not just the images overlap, but also their themes. Gender, femininity, body image, capitalism, and the space of life itself—all return, and all return as product, as artifice, and as constraining. When nature visits this dystopia, in rows of potted plants, it appears as culture. As for Rottenberg's past images, they appear almost incidentally, more as quotation than as excerpt. One woman deposits a soft, white blob onto an open palm, and more of the substance forms a thread across one frame or green, abstract texturing across another. They, too, though, appear as a contrivance or maybe even a work of art.

In quoting herself, Rottenberg has also cleaned up her act. The photographs share crisp colors and a sharp focus. The maze in space and time has become a grid in two dimensions. The goo takes up less space, and the people look less scary—at times almost normal. That black woman is almost making eye contact and maybe, just maybe, almost smiling. That almost naturally points to yet another constraint or convention, the detachment and allure of the gaze in fashion magazines.

Surreal or not, the photographs permit smiling. Maybe I should have laughed at or with the video all along. Sure, the smiles now come a little too easily. Who can resist those wiggling limbs? And sure, in selling out, Rottenberg is stuck repeating one idea. It is a stylish idea at that.

Puppet theater

Robert Bresson treated each film as a lesson in patience. In A Man Escaped, a prisoner of the Nazis attains freedom with a hairpin, an iron spoon, and the tiniest of repeated movements. Pickpocket explores crime and punishment through close-ups of a book and a thief's hands. Balthazar follows a farm girl's cherished donkey through several owners and a lifetime of abuse. In its parable of saintliness, change comes only to those who accept stasis. Karen Yasinsky wants to translate that stasis into stop-action video.

Claymation and puppet animation seem everywhere right now. They rebel against slick digital video, while appropriating both pop culture and new media's art-world ascent. Their rhythms signal childishness, but also violence and manipulation. Lauren Kelley's black Barbie doll learns that lesson the hard way, as the struggling librarian in Get Bones from 88 Jones. So, in a sense, do Jessica Ann Peavy and Deana Lawson—featured with Kelley in "The Brand New Heavies." With their choppy video and untitled film stills, one could think of their work, too, as stop action.

No wonder Hank Willis Thomas chose claymation five years ago for a Harlem street fight. Nathalie Djurberg and Natalie Frank have adapted it to the longings of children in a dangerous world. And Djurberg has returned to it again with a very different image of black femininity. Her fragile dancer made the most of a fantasy tea set, of sugar cubes and chocolate sauce. Something brown also smeared the gallery's curtains like excrement. It suited the Swedish artist's Freudian fairy tales, but what would it mean to African-American women?

Karen Yasinsky, too, uses puppets to mingle violence and innocence. And she, too, likes the look of a fairy tale. I Chose Darkness compresses Bresson's movie into nine minutes. As the title suggests, she asks how one consciously or unconsciously embraces suffering. As with Thomas, Kelley, and Djurberg, that includes the suffering of others. Marie identifies with her donkey, who lies on the grass or reeds with its legs limp and broken, but the narrative center has shifted very much to her.

A puppet's clumsy movements serve here as a metaphor for tentative gestures and awkward feelings. As Bresson might wish, not much happens. Marie hugs her donkey, but also the boy who twists her fate. She sits alone over a spare dinner with downcast eyes. She touches her belly meaningfully. While a puppet's unchanging features and always bright colors cannot show emotion, its sheen comes close to tears.

The limits also help the artist draw back from direct depictions of violence. It appears only in the gaps between scenes and in rough cuts, and this, too, accords with Bresson's focus on endurance. On the other hand, it tends to sentimentalize his plot. Stop-action video can add humor, undermining how film violence gives pleasure. Here it risks boiling the French movie down to a trailer. It does, however, clarify the range of associations that so many are finding in the same retro medium.

Insomniacs

Yasinsky's heroine still cries herself to sleep. Like Damien Hirst, Zoe Beloff's "Somnambulists" can make art in their sleep. Only who exactly is pulling the strings? Is it a woman's inner demons? Is it a male medical establishment or the artist herself? Is it the popular entertainment that plays behind them all?

Beloff supplies her own private history of an obsession, the modern-day obsession with psychoanalysis. Her miniature theaters teem with ghosts. In the smaller models, translucent specters act out hysteria, as described around 1890 by Pierre Janet, a decade before Freud's early work. A larger video has less disembodied, more gaudily dressed actors out of a nineteenth-century music hall. The master of ceremonies marches his all-female cast—or perhaps patients—through their motions. The colorful costumes and wooden theaters go back to the commedia del arte, rooting the malaise in Western art history as well, but were psychology and art all along just theater for the masses?

Janet, like Freud, studied under Jean-Martin Charcot, a French neurologist. Critics ever since have seen them as "medicalizing" cultural biases, trapping women in a theater of their own devising, with the therapist as director. In Freud's interpretation of dreams, the patient acts out the drama of the unconscious, with the dream symbols and symptoms as its script. In Beloff's vaudeville act, the dream interpreter enters as both dramatist and fellow performer. Especially in the ghostlier projections, the spectator, too, enters into the hallucinations. Beloff's trickery supplies grounds for disbelief in the whole affair, for she makes psychoanalysis and art alike part of the performance—and thus part of the illness, too.

Freud, the co-author of Studies on Hysteria, still gets people hysterical, but he anticipated his critics and then some. He came to find his early collaborations confining and reductive. He opened any conduct to interpretation, including the art of interpretation—on topics from the psyche and war to Leonardo and van Gogh. He was also the first to implicate his public in the same sexual habits as his patients, which is precisely what made him so notorious. What rescues Beloff from a lecture on Michel Foucault is that she identifies the artist and gallery-goer, too, as stage managers, audiences, desirers, and visionaries. Her preference for 3D glasses over, say, artist holograms sets her handmade theaters at a historical remove, but it also updates them as retro chic.

Glib, overweening scripts about glib, overweening scenarists can quickly become dogmatic and dated themselves. If anyone has medicalized cultural norms, how about the dominance today of drug therapy and of genetic explanations for gender difference? One could almost forget the whole thing and buy the artist's book of source material, compiled with Christine Burgin. Besides, scholars and feminists have been raking over these coals for years now without her help. Beloff's drawings to accompany the theaters look especially cluttered and schematic. Yet her soap operas come alive in their smaller theaters, where the conceptual parallels multiply and their translucency fades into memory.

If a comedian is going to repeat old jokes about neurosis, it helps to turn them on herself. Marsha Pels has the usual sources of guilt, such as sex, death, and her mother, although not necessarily in that order. Her installation memorializes her mother and a "cowboy"—the former dolled up in fur even in her bier, the latter as the burned-out skeleton of a biker. She has learned something from both, such as when to obsess over details and when to run a little free. Still, even once one understands the dead male as a lost lover, the pairing feels arbitrary, like the beginnings of a longer, more delirious obsession with death. As for her mother, one will just have to wait and see how Pels takes advice from beyond the grave.

Mika Rottenberg ran at Nicole Klagsbrun through February 28, 2009, Karen Yasinsky at Mireille Mosler through April 11, and Nathalie Djurberg at Zach Feuer through January 24. Zoe Beloff ran at Bellwether through October 4, 2008, and Marsha Pels at Schroeder Romero, also through October 4. A related review looks again at another proud hysteric, Carolee Schneemann, in feminism, video, and performance.