Curses, Rituals, and Dreams

John Haberin New York City

Lara Schnitger, Fred Tomaselli, and George Condo

Maudi soit à jamais le rêveur inutile, wrote Charles Baudelaire. "Cursed be forever the useless dreamer." Anguished and reflective as always, he could have been thinking of art.

He could definitely be thinking about the mood in New York. Lara Schnitger at SculptureCenter quotes that very line, as part of a very dark and silent ritual. Downstairs the artists go so far as to draw blood. Meanwhile, out in Brooklyn, Fred Tomaselli creates paintings from black backgrounds, actual drugs, and the fall from paradise. Baudelaire did say "one must be drunken continuously," but this is serious, at times dreadfully serious, business. It takes George Condo to treat transgression as clowning and the Old Masters as a publicity stunt.

Dark satanic trolleys

Strange rituals are taking place in Long Island City. William Blake did not have SculptureCenter in mind when he spoke of "dark satanic mills," but the former trolley repair shop holds more than he knew. All four artists in its basement tunnels make their practices hard to pin down. One of them can hardly decide which stereotype to parody—a racist portrait or a portrait of racism. Yet the center's installations work best when they respond to its interior as they do here, and at least one artist refers to the neighborhood as well, although darkly. Apparently more than just a candidate for Senate and summer movies aimed at teenage girls have dabbled in Satan worship.

Josh Tonsfeldt films neighborhood trees for up to seven hours, while voices fade in and out. I could hardly help associating a child's delight with the torment of a spider in a shorter video two tunnels away. Only an infant's photo and a child's encyclopedia punctuate more bright lights and a long wooden railing, somewhere between handhold and obstacle. Someone has stumbled here in the dark, and someone else is the worse for it. Justin Matherly's headless gods might accept the sacrifice, and only he knows that their plaster covers crutches and other found traces of infirmity in place of a wire armature. Unfortunately, they lack the arms and organs to take part in his catalog of sexual perversions on a poster around the corner.

Lior Shvil aims for broader, more comic strokes on video. As The Kosher Butcher, with eyes gleaming and the addition of a black hooked nose, he makes a plastic bag serve as a blood-spattered body, and the installation retains as fake as possible a take on human organs. Viola Yeşiltaç hints at even more obscure deeds, in hanging straps of leather, folded chairs, and titles like Vier Gaulker (four jugglers). All I can say is that something serious is going on, except when it is not serious. As one of Matherly's rambling titles has it, The degenerated instinct which turns against life with subterranean vengefulness; see you again in your muck of tomorrow.

This is not a forgiving view of human nature, no more than the butcher shop of Paul Thek. In fact, Lovett/Codagnone wants you to know, Your Hero Is a Ghost. Their metal bleachers in the Maya Lin sculpture garden (with the assistance of Tom Zook, a Yale architect) are all set for a sorry spectacle, but they are impractically tall for seating, and they face a brick wall only a few feet away. A soundtrack reminds you that it is all your fault—yes, you, you "gasbags," "lowbrow," "middle class," "congressmen," and worse. The artists cite as inspiration Offending the Audience, Peter Handke's razor-sharp play from 1966. However, they treat art and politics alike as liberating.

Lara Schnitger packs more menace and ambiguity in the large central hall, where the spectacle is still in progress long after everyone but the viewer has died. Curtains printed like black brick encircle an almost prone fabric figure, face up and waiting for the knife. Far taller black constructions stand guard outside, and a mess of foam and steel tentacles hangs above. It might be a corpse or a divine persecutor. Nothing moves, but Schnitger describes the curtains as eight separate sculptures. From the inside each one looks like a caped guardian—or perhaps what Charles Baudelaire called the flowers of evil.

She also makes the gender and complicity of the actors less clear than first appears. One eye of each curtain sheds a red scarf, ambiguously dripping with tears or blood. Hanging like a stocking, it feminizes the male tormentors, and the spaces between them have the rounded outlines of an earth goddess. The taller guards thrust out a single arm (or maybe penis) like kung fu fighters. Yet they, too, are fabric stained with hearts. Their heads bear the label Hippolyta, the Amazon queen and one of Baudelaire's femmes damnées.

The Dutch-born artist uses that same name for the sacrificial victim at the circle's center. Are the hearts feminine or biker tattoos? Does the victim bear chains or jewels? And who exactly are the Two Masters and Her Vile Perfume? Maybe better not to ask. Try instead a little useless dreaming.

Popping pills

This Christmas, Fred Tomaselli is making a list and checking it twice. One sketch pairs his favorite bands with his favorite species in nature, and he has plenty of favorites. Another throws in drugs, like an inventory of altered states of consciousness. Those bands, birds, leaves, and sex and drugs are also an inventory of his art—or is it the other way around? He uses paint, pills, and collage to depict an altered state of nature. At their best, the large paintings induce some mind-altering of their own.

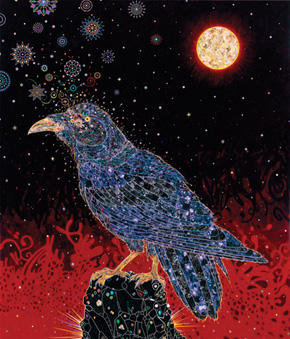

Tomaselli is an observer of both nature and his mind's eye, and he may not care all that much to distinguish the two. He may need to glue so many pills to canvas just to stay straight. Naturally the largest paintings are the most realistic and the most hypnotic, and almost all take place at night. That includes the expulsion from Paradise, bodies reduced to swollen arteries coursing through flesh-toned silhouettes. A ghostly red radiance drives them out, as birds, butterflies, and flowers blend into stars. In more ways than one, Adam and Eve are having a bad trip.

The Brooklyn Museum calls it a midcareer retrospective, although the artist is in his fifties. Born in Santa Monica, he flourished in downtown LA, which has something to do with his obsessions as well with as his distaste for formalism or conceptualism. He settled some time ago in Brooklyn, another good place to collect fallen leaves and wonder if that is all there is to nature. A painting's large scale, fine line, and deep colors can easily make it seem that way, as can some less interesting overlays of psychedelia onto newspaper front pages. The small, two-room retrospective shows little obvious development, and it is at its best at its most seemingly realistic. Which is not to say that anything looks realistic for very long.

The Brooklyn Museum calls it a midcareer retrospective, although the artist is in his fifties. Born in Santa Monica, he flourished in downtown LA, which has something to do with his obsessions as well with as his distaste for formalism or conceptualism. He settled some time ago in Brooklyn, another good place to collect fallen leaves and wonder if that is all there is to nature. A painting's large scale, fine line, and deep colors can easily make it seem that way, as can some less interesting overlays of psychedelia onto newspaper front pages. The small, two-room retrospective shows little obvious development, and it is at its best at its most seemingly realistic. Which is not to say that anything looks realistic for very long.

Tomaselli's art can veer on kitsch, in both its imagery and its materials. The lists without hierarchies resemble less science than late nights in a dorm room—with maybe the same inspirations and chemical stimuli. So does the way one list's subject can abruptly veer into another's. The book and magazine clippings give people bulging, discolored muscles—not unlike Arcimboldi's faces assembled from painted fruit and vegetables in the late 1500s. Mannerism, too, liked black backgrounds and decorative nudes, as with Lucas Cranach. By coincidence, Arcimboldi has his own small exhibition in Washington.

People keep noting parallels between Mannerism and the present, with good reason. The first reflects endlessly and self-consciously on the Renaissance, the other on Modernism. Tomaselli derives from Surrealism and Pop Art as well as any number of other currents (and I just received a gallery invitation from Chelsea to look at taxidermy animals that Maurizio Cattelan might appreciate). Both periods are international in reach, and both seem all over the map when it comes to style, too. Nationalism was newly powerful in the sixteenth century as well, much as the Brooklyn Museum is sticking up for a Brooklyn artist. The bright colors and swirling lines may even have something in common with street art from Kenny Scharf.

It is a charmingly wild but narrow vision, and the show in fact gains from narrowing it further. The selection gives more emphasis to Tomaselli's natural imagery and myth than to his pattern and decoration. That includes a raven in profile against the moon—or an owl's fearful symmetry almost out of William Blake. One can even see guilt, fear, or melancholy in the blackness. No wonder he likes the story of Adam and Eve, who had this thing about forbidden fruit and ran into an accusing angel. Pills and paint go into the piercing whiteness of the owl's eyes.

Old shocks and Old Masters

Alas, I have confession to make: I hate the Old Masters. At least I have little patience for George Condo, and he is an Old Master, right? Everyone says so, starting with the artist. One can hardly read a word about him without encountering the claim for his "fake Old Masters," and a fawning New Yorker profile must have repeated it a dozen times. Other dead white males may object, but dead men tell no tales.

In all fairness, the self-taught artist called his early work "fake Old Masters," which makes more sense. At Pat Hearn's pioneering East Village gallery, he grew close to Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, and later Tony Shafrazi, whom one might call fake street artists, unlike street art's smart simulation from Raymond Saunders. Condo alone sounds like a bad joke about street art and gentrification, although he came by the name honestly, through his parents. Those were crazy times anyway, long before one could imagine a sleek New Museum on the Bowery. Friends also included Philip Taaffe and Julian Schnabel before Schnabel turned from Neo-Expressionism to the movies. Critics like to call Condo the missing link between them and painting today.

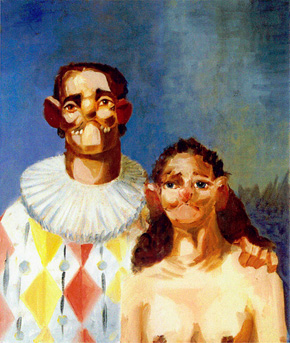

He means the homage to the past sincerely, though, in portraits that quote everyone and no one—from Velázquez portraits to Picasso's Neoclassicism. One can sense the ambitions of a classicist and postmodern regrets in his narrative paintings, too. They come lumped under the titles "Manic Society" and "Melancholia," positively dripping with piety. If the bulbous heads look more like Sylvester J. Pussycat, think of Arcimboldo's Mannerist faces composed of fruit. If he has put them all through a salacious wringer, think of Willem de Kooning and Francis Bacon. Goodness knows Condo has.

He also prides himself on what David Hockney likes to call the "lost techniques" of the Old Masters, although there, too, he has a love-hate relationship with history. He may have influenced John Currin and Lisa Yuskavage, but do not expect academic drawing. Rather, he builds up portraits in oil and then rubs them out—before building them up again and maybe adding Sylvester and Tweety. He found his connection to the textbooks through just that process, which accounts for a portrait's dark background or the traces of figures in what he calls his "abstractions." Jacques Derrida might term it the Old Masters "under erasure." The ambivalence of a literary flair and a bad joke go into Condo's frequent long titles as well.

I can appreciate the love-hate relationship, but I could do with far more depths of love or hate. It takes more than a drab background to become an Old Master, and indeed one can often spot a workshop copy by the haste and simplicity beyond the faces. The Old Masters include too many periods and styles anyway to mean much—except to feminists and multiculturalists who despise the term. It takes more, too, these days than cartoons and sex to shock. Eliot Spitzer as The Return of Client-9 or inane Stockbrokers would work quite well as New Yorker cartoons, and Elizabeth II as The Insane Queen will scandalize only someone who truly hopes for a scandal. And that someone helps explain Condo's outsize reputation, especially in Europe.

The show, organized by the Hayward Gallery, calls him an "artist's artist"—but I think of him as a collector's artist, from a time of exploding overseas markets and new wealth. He delivers the cachet of the Old Masters, the stylishness of provocation, the accessibility of a comic book, and just enough sophistication to know that the three cancel out. The New Museum is onto something when it hangs the portraits Salon style, as the kind of history that art history wants to repress. For me, that act of repression becomes vivid only with the "abstractions." As the acrylic and charcoal figures move in and out of view, a struggle with de Kooning's generation comes to life. One can see why Philip Guston went through it before, on his way from abstraction to cartoon realism and self-abuse, and one can see why so many painters now are struggling to find their way back.

Lovett/Codagnone, Lara Schnitger, and other projects ran at SculptureCenter through November 29, 2010. Fred Tomaselli ran at The Brooklyn Museum through January 2, 2011, George Condo at the New Museum through May 8. A related review looks at Condo drawings.