Never Explain

John Haberin New York City

Edward Hopper: Drawings

"The preliminary sketches would do little for you in explaining the making of the picture." And here you thought they were the making of the picture.

Edward Hopper may not have convinced even himself, but one can see why tried. Hopper was writing the director of the Addison Gallery in Andover, Massachusetts, about Manhattan Bridge Loop. Maybe he felt pressured to explain his art. This was 1928, when buyers were hesitant, and modern painting took explaining. And plainly he refused. This was modern art, which was supposed to resist easy explanation—and still does.

Still, am I wrong to hear him questioning himself? For "Hopper Drawing," the Whitney gathers eighteen canvases, including some of America's best-loved paintings, and gives each one a history. The loan from Andover comes with six preliminaries—a closely related oil, a watercolor, a crayon used normally in lithography, a charcoal, and two in the dense chalk that Hopper loved most. For New York Movie alone, from 1939, the show has fifty works on paper in chalk, charcoal, and pencil. This man took his time. Why, and does that make his paintings about observation or about abstracting away?

Sketches more than drawing

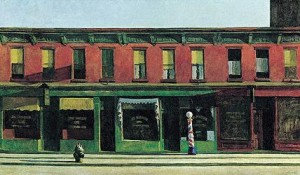

Much of the show's pleasure comes in asking. It gives Edward Hopper a history, starting in 1899, at age seventeen. It follows him in his studies, first at the New York School of Art and later at the Whitney Studio Club, the precursor of the museum. It shows him setting up his Manhattan studio just north of Washington Square, walking the streets, riding the subway, and at home in Cape Cod. It displays his most famous painting, Early Sunday Morning from 1930, on an easel unframed, as if he had gone out to check its accuracy against the storefronts on Seventh Avenue a few blocks north. Maybe it was the loner in him as much as the traditionalist, but Hopper built his own easel.

Mostly, though, the show is about those paintings and how they came to be. Eight modules offer a kind of miniature retrospective, each with one or two paintings from much the same time and place. While the oils draw widely on other museums, all but half a dozen of the more than two hundred drawings belong to the Whitney itself (from a stash of well over two thousand, a bequeath from Hopper's widow). As with the artist's years at the Whitney Studio Club, it is asking about the origins of the museum, too. Maybe it is also paying a first farewell to Madison Avenue, on the museum's way to the Meatpacking District. The modules for preliminary sketches surround a square for Hopper's training and methods, a tribute to Marcel Breuer's freestanding walls.

That leaves the enigma of just what Hopper was doing, a puzzle drawn out elsewhere by John R. Shipp. He completed surprisingly few paintings, each of them an enigma as well. One remembers them for that strangeness, in the early morning sunlight or a diner at night. And somehow the closer he came to a subject and a painting, the more the drawings look unfinished. They do not dwell on the outlines of figures or a display of skill, like J. A. D. Ingres and many an artist of the past. They do not focus on tonal variety, to create light itself from wisps of sunlight and smoke, like Winslow Homer and his American stories or Impressionism.

They move fast, so that one wants to call them sketches more than drawings. Sometimes, especially late in life, the crosshatching goes well beyond mass or shadow, leaving it open what will emerge. Increasingly, too, they rely on the properties of charcoal and fabricated chalk, so that the main outlines correspond to darker blacks. They are more concerned with the whole than with form, color, or light. Others, sketchier still, pursue a single detail, with much of a sheet often blank. For New York Movie, the Whitney has tracked the many elements of forgotten architecture to four different movie houses—primarily the Palace Theater in Times Square.

"Hopper Drawing" is as much a detective story as eye candy. Carter E. Foster, the Whitney's curator of drawing, places one with Hopper as he explains to himself what he insists resists explanation. That alone says something about the painter's place in American art. He has always been the great American modernist for audiences who distrust modern art, even as he questions the relationship between realism and vision. The show ends in Massachusetts, first with A Woman in the Sun from 1961, a nude holding a cigarette and turned toward an open window as if expecting something more. And then in 1963 comes Sun in an Empty Room, in which she and the very logic of the room's layout have melted away.

The show is probably more fun if one works backward, to compare paintings with drawings and drawings with one another. By themselves, the studies just will not do what one expects from art. In that sense, Hopper was right. And while his early work stands better on its own and found such champions as Edith Halpert, it is also duller. Still, the story begins there. Born in 1882 in Nyack, north of the city, he preceded Modernism, and his encounter with it and New York shaped his art.

On the move

Hopper's early drawings do not look at all preliminary. They are accomplished enough, in the manner of nineteenth-century American realism, but they already challenge the ideal of polish. They picture an urban scene, of casually dressed men and women, a matchbox, and a bullet. They run quickly through faces and hands, often as not his own, to the point of caricature. They seem preliminary not to paintings but to magazines. When he takes up watercolors, they owe something to the fashion for Japanese art and a great deal more to Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

He studied at the New York School of Art with Robert Henri, who also taught George Bellows, Patrick Henry Bruce, Rockwell Kent, and Guy Pène du Bois. If there was an American century, no one did more than Henri to shape it—except perhaps for Alfred Stieglitz, and Hopper would have found his way easily to Stieglitz's gallery at 291 Fifth Avenue after 1908. Henri's high-contrast realism derives from Dutch painting and Edouard Manet, and the Whitney has a pen and ink copy after Manet's Fifer. Maybe Hopper was still thinking years later of Henri's portraits, with their glossy lips and eyes, when he gave a clown lipstick and eye makeup. Fellow students recognized his talents, and Bellows helped install the Armory Show, where Hopper sold his first work. If that 1913 show introduced modern art to America, Hopper was part of the introduction.

Still, he was hardly precocious. He had his first success in his forties, with a show of watercolors in 1924. At the Whitney Studio Club, from 1920 to 1925, he even took a step backward toward academic practice, with a good six hundred nude drawings. He was pursuing magazine illustration as late as 1925. As late as the 1940s, a sketch of his wife, Jo, looks curiously inert. Fortunately, he had been pursuing all along an education on his own.

Still, he was hardly precocious. He had his first success in his forties, with a show of watercolors in 1924. At the Whitney Studio Club, from 1920 to 1925, he even took a step backward toward academic practice, with a good six hundred nude drawings. He was pursuing magazine illustration as late as 1925. As late as the 1940s, a sketch of his wife, Jo, looks curiously inert. Fortunately, he had been pursuing all along an education on his own.

That included time in Europe, from 1906 to 1910, and it paid off. If he wanted the painting of modern life, he could find it in Paris. The Whitney has a pocket sketchbook, and then he returned to some of the same streets on a larger scale, to pin them down. The show's first paintings, by the Seine, already bathe in fields of light, with people in shadow. They seem less composed than stumbled upon. With Hopper, the viewer is always in transit, while everything one sees is still.

His first major painting, Soir Bleu, remembers Paris, although he painted it in New York in 1914. It also returns to high and low society, with a vengeance. That clown shares a table with someone in street clothes while smoking a cigarette. Where Edgar Degas pursued realism to the circus, in and out of Degas monoprints, Hopper skips the theater. The painting poises on the edge of allegory while refusing a moral, and that, too, will characterize his art. It is about the down time of a pose.

Manhattan Bridge Loop cements the connection between the city, where everyone is always looking or avoiding another's gaze, and the observed. It has a pedestrian walkway in the foreground, as a pool of light, and a street lamp's early-morning shadow. It is also devoid of life. Hopper glimpsed the scene from the subway as it crossed the bridge, as he did for a painting that year from the Williamsburg Bridge. (Wall text calls it the L, where it means to say the el, and this is not exactly either, but never mind.) Hopper is in his element and on the move.

Drawing back

Hopper's world is very much his own, from New York to New England. A rectangle marks how he will crop Rooms for Tourists from 1945, as if seen through a car window. He will also turn to himself for a model or to Jo. At the same time, no one belongs, whether Jo in the military uniform of an usher at the Palace. These are places one goes on the way elsewhere—the subway, the movies, a gas station, a cheap hotel, or the streets on a weekend dawn. One comes for comfort or necessity, without quite finding either one, as in an office at night where no one speaks or a diner with coffee but no food.

The scenes push the boundary between natural and artificial light. Sometimes drawings repeat almost the same image, but as darkness and light. Maybe one image describes the place, the other the time. Rooms for Tourists starts in daylight, before taking on the night. The light can promise a human connection while enforcing isolation. It can stand for observation or artifice.

Over time, Hopper pushes that sensibility further toward naturalism and Surrealism, to the point that one can hardly tell them apart. With the last paintings, yellows and greens are closer to nature and further from conventional narrative. His naked woman faces the window, unseen except for sun-drenched draperies blown inward. Between them, another window presents a more unobstructed view, as if to say that hers has nothing to do with ordinary vision. She could be meeting sun as in a ritual or as her due. She could be watched or watching.

Hopper's fragmentary sketches, of hands or architecture, may make his process seem additive—the slow accumulation of precise observation. It can come as a shock to see that the empty room follows the room with a woman and a vision. His art has more to do with recombination, as of the three theaters. Nighthawks in 1942 borrows the window from the Flatiron Building (which holds through the run a reproduction as full-scale simulation), the intersection from Greenwich Avenue and Eleventh Street, and the diner from Greenwich and Twelfth. And recombination also means abstracting away from specifics, in search of light and the whole. Sometimes he annotates the parts with their tonality or color, because he can nail them only in paint.

"Hopper Drawing" could serve as a short history of New York in the last century, without ever quite picturing it. Hopper stops short of abstraction, while increasingly refusing illustration. He draws back from the currents of realism or Modernism, while bridging them both. By the end he approaches the postmodern allegories of Eric Fischl and David Salle. As with the clown from the first, he leaves it to the viewer to resolve the implied sexual tensions. He also leaves it open when he is posing his subjects and when he is just passing through.

One may never really find him in his drawings, just as he is never fully a participant in his own drama. They are not always revealing or even all that impressive, but then his art depends on a familiarity that resists explanation, a kind of drawing back. One goes to his drawings to see not just what he adds, but also what he leaves out. Maybe that, too, is part of why he hesitated to say more about them—and why they matter. Every painting, he wrote in that letter to the Addison Gallery, is "planned very carefully in my mind before starting it." Still, for an artist, the mind includes the hand and the paper.

"Hopper Drawing" ran at The Whitney Museum of American Art through October 6, 2013. A related review looks at Edward Hopper in retrospective, with "Hopper's New York."