The American Bad Dream

John Haberin New York City

Real/Surreal, Reginald Marsh, and American Surrealism

Sure, go to the Whitney for American Surrealism, and you will find it. You will find nightmares in the very titles of The Dark Figure, Night Shadows, and Terror in Brooklyn. You will find worlds under glass and intricate fantasies, intertwined bodies and deserted streets. You will find a girl on the brink of sexuality, in Philip Evergood's Lily and the Sparrows. You will find signature images, like George Tooker's The Subway, with its maze of corridors and its figures trapped and afraid.

Sure, but also Grant Wood, Rockwell Kent, and Andrew Wyeth? What of small-town America and American realism? What of the character that sustained them through the Depression? What, for that matter, of the character that left them painfully out of touch with modern art? Is that all a myth? And what of Edward Hopper?

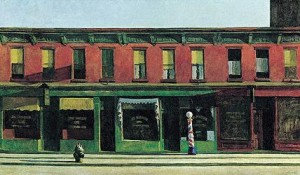

Yes, Hopper, and yes to everything that came before. "Real/Surreal" sticks to the permanent collection, in another period of depression economics. Like a show across town of Reginald Marsh and his peers, it offers an insightful portrait of the 1930s and 1940s. It does not so much build a case for neglected artists, however, as connect the dots, with Hopper's Early Sunday Morning at its center. It also helps explain why realism and Surrealism look so different once they cross the Atlantic. With Llyn Foulkes, now the subject of a separate review, they may survive in Southern California even now.

The precision of loneliness

America came late to Surrealism and Surrealist drawing, as it did to so much else. Man Ray had played a part in Europe, but things took off after 1914 under pressure from artists like Giorgio de Chirico, catastrophes like World War I, and Sigmund Freud with The Interpretation of Dreams fourteen years before. It was at its most menacing through the early 1930s with artists like Max Ernst and Alberto Giacometti. One can always find roots in Pablo Picasso, Henri Rousseau, or even Romanticism, just as with everything else modern. Here, though, Man Ray appears in 1938—with a pool table tilted wildly upward, its bright green leading to colored clouds. The next shot promises to burst the picture plane, like the cannon of On the Threshold of Liberty, by René Magritte.

Then again, the table holds only cue balls, ever so elegantly apart. And if they did move, they would surely tumble backward, to where the perspective already crowds out a human actor. The Whitney pairs this with another ball isolated on another table, by Helen Lundeberg the year before. The orb parallels a doorknob, and the comet trails in a display on the floor parallel the table's shadow on the floor. It looks both old fashioned and scientific, amateur and coldly professional, inviting and askew. Then from there one moves to still more points of light on a deserted surface, in a 1939 landscape by Grant Wood.

Is this Surrealism? Maybe so, and if it still has room for optimism, Wood turns up again. His Shriners sing to symbols of anything but grass-roots democracy, Egyptian pyramids—and the Whitney sets it beside an early Philip Guston, even before Guston's abstraction, much less Guston's self-doubt. In another Wood lithograph, snow-tipped wheat in fact resembles a Klan march. As for Kent, his dancer looks, as he himself said, "half crazy," and Wyeth's Winter Fields foregrounds a black dead bird. Someone looking to realism for rural virtue will have to look again.

"Real/Surreal" has walls for city and country, plus rooms for human bodies and factories. It gets its kick, though, from pairings like this. It reconsiders realism and even Cubism as aspects of Surrealism, much as MoMA rewrote its own history by displaying German Expressionism. It is a tribute to the collection and the building, just when the museum has chosen to relocate to a new Whitney Museum in the Meatpacking District. It uses the flexible architecture for one big room, broken by columns for additional display space—and with a trapezoidal window onto a back room that mimics Marcel Breuer's windows onto the street. (It is technically the second in a series, but the Whitney has been rehanging the collection for years now, at least since it extended its display space to five floors.)

Precisionism, too, fits right in. Its factories look lifeless, like the coal-gray silhouette of Ralston Crawford's foundry. Charles Sheeler's Detroit could presage its failure in contemporary photographs by Andrew Moore or pressure on the Detroit Institute of Arts and art in Detroit today, and the numbers running down his right edge could stand for dehumanization. Nor is Crawford alone in framing his composition with crosses, from signs or utility poles. Charles Burchfield does in Winter Twilight, with a man shivering beneath heavy clouds and artificial lights. Emlen Etting's poles carry no wires, and the railway tracks across dry strokes of brown converge to nowhere.

And then there is Edward Hopper, beloved for loneliness. Night Shadows is his, and the long shadows in Early Sunday Morning could evoke darkness and asymmetry—or stability and sunlight. One is cast by a fireplug, and at least one is cast by nothing visible at all. The Whitney points to the unreal tilt of a barber pole and to the skyscraper peeking out behind the warm red brick. The pairing could mean harmony or change. At the very least, it means a painter's clarity of vision.

Everyday Surrealism

Edward Hopper is still one of a kind, and so is prewar American art. Some of the most prominent artists do come from Europe, like Yves Tanguy and Pavel Tchelitchew—along with the most outrageous anatomy and color. Like Hopper, though, Americans can be comforting even in loneliness. The customer of Henry Koerner's barber shop looks like T. S. Eliot's "patient etherized upon a table," but I would come for the conversation, the violin, or the monkey on the floor. Even Tooker's subway station looks as familiar as Union Square today, only cleaner and better lit. The men lurking in tight spaces must have working pay phones.

The Whitney's big break with the canon is comforting, too. It includes more women than you might expect (although, hmm, not Dorothea Tanning), starting at the entrance with Kay Sage. Her jumbled railroad tracks, fallen flags, and blank walls actually date quite late, to 1954. One could take them as a handy outline of what lies within, from Sheeler's factory and Etting's railway to Hopper's lightness and Tanguy's illogic. The show also wants attention paid to Paul Cadmus and Jared French, gay or bisexual painters in tempera, for whom anatomy is psychology. They, too, come after the war.

The Whitney's big break with the canon is comforting, too. It includes more women than you might expect (although, hmm, not Dorothea Tanning), starting at the entrance with Kay Sage. Her jumbled railroad tracks, fallen flags, and blank walls actually date quite late, to 1954. One could take them as a handy outline of what lies within, from Sheeler's factory and Etting's railway to Hopper's lightness and Tanguy's illogic. The show also wants attention paid to Paul Cadmus and Jared French, gay or bisexual painters in tempera, for whom anatomy is psychology. They, too, come after the war.

What, then, makes this Surrealism American—or what the National Academy Museum in 2005 called "Surrealism USA"? If it seems less of a nightmare, think of the contrast between Europe in turmoil and America between the Dust Bowl and World War II. It is about change, but the slow and unnerving pace of change. It makes few political demands beyond Robert Riggs's Children's Ward and Guston's KKK. Technology is part of that change, from utility poles to science as totem in Peter Blume's Light of the World. Even so, it can be part of the promise, like Harold Edgerton in his electrifying photography experiments at MIT—capturing a dove in flight, a football kick, or a bullet literally "cutting the card."

When change threatens, it threatens an American dream. It overruns nature, like the family farm on a hill for Joe Jones or the Leigh Valley for Henry Billings. At the same time, it embraces popular culture and folk traditions, where for Lyonel Feininger in Europe urban life was an ugly circus. It allows Mabel Dwight's crowd to enjoy their fears, in a movie theater. It allows Andreas Feininger's collage advertising and Joseph Cornell's obsessive collecting. It allows Martin Lewis's flappers to look like a sexy shadow army.

Between farms, factories, and the movies, it grounds Surrealism in the everyday. Say all you like about Freud's dreams, but Americans prefer a recognizable world. The concreteness makes for some backward-looking realism but also hints of much later geometry, Pop Art, and appropriation. It also allows an alternative history to the Whitney's, pointing entirely to the future. Instead of realism, one could connect the dots to Abstract Expressionism. Imagine another exhibition entirely.

It would have serious nightmares, like Arshile Gorky, and it would observe that Willem de Kooning had his first show at Charles Egan gallery the very year before Cornell. It would have a darker subway platform, as in early Mark Rothko, soon on his way to Rothko's floating color. It would have Jackson Pollock and the long struggle to put standing figures, amoebas, and Surrealism behind him. It would have Louise Bourgeois, Bourgeois in painting, and Bourgeois prints or Eva Hesse, who adapted Surrealism to Minimalism and beyond—and it could carry the fabled American weakness for mythmaking to Dana Schutz and others today. That, though, would be a different show—and it draw on a different permanent collection. For now, one can enjoy a more blatant revisionism.

He came out swinging

At the dawn of the 1930s in New York, where were all the New Yorkers? Asleep, no doubt, on Edward Hopper's early Sunday morning, but just wait until they got going. Wait until they started packing the subways, the chorus lines, and the movies. Wait until they headed for the burlesque houses and the beach. Reginald Marsh, for one, could not get enough of them, but had he come any closer to what the New-York Historical Society, through September 1, calls "Swing Time" and to New York? Where Hopper saw intense light, long shadows, and a redeeming and a terminal isolation, just wait.

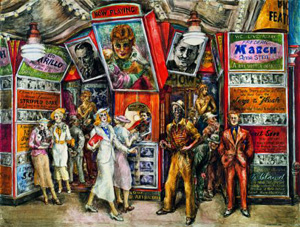

Closeness for Marsh was hardly the point, no more than for Hopper in a diner after midnight. Marsh, just a year older than Hopper, painted not people but demons—and crowds. They press against the picture plane, so that neither he nor anyone else can join them, or they fade into each other and the dark. They stand above, from Minsky's in Times Square to the Savoy in Harlem, their feet cut off by the picture plane and from the ground. Quick scrawls and tawdry highlights dart across their bulk. Look but do not touch.

The demons are women—and when men do appear above, in movie marquees, the demons lurk below. They never expose much in the way of flesh, beyond a lower leg here and there, but the temptation is enough. If Marsh has his hang-ups, and he does, he also belongs as much to the history of caricature as to journalism, expressionism, or confession. He sketched for the Daily News and The New Yorker in the 1920s, and even the rare sympathetic faces (female, of course) sport bug eyes and glasses. Although he learned his bulky forms at the conservative Art Students League, where Kenneth Hayes Miller and Guy Pene de Bois tempered their Modernism with reverence for the past, Marsh alone stuck to egg tempera on composition board and Masonite. And he liked it not because of its traditions of gilding and hand-ground pigments, but because it dries fast, so that painting became sketching on the spot.

A fellow student, Edward Laning, has Renaissance clarity and symmetry in mind when he paints brightly modeled riders by the twin stairs of the el. Marsh breaks the clarity and the symmetry. Where another fellow student, Raphael Soyer, sees faces alone on the subway or in the unemployment line, Marsh breaches the space between bodies. Like them both, he paints in and around Union Square, in what passed as the Fourteenth Street School. Still, he is not like Hopper prowling his home turf in search of every detail and every displacement. Vulgarity for him is an end in itself.

It is a simple enough vulgarity, from a simple enough artist. Walker Evans or Alfred Gescheidt, too, rode the subways of New York, their camera hidden to capture riders off guard, as themselves. Weegee and Lisette Model both used photography to convey sexual and racial ambiguity. Marsh took photos of his own, but with little room for individuals, for introspection, or for ambiguity. He is not a realist like George Bellows, cutting corners when it comes to the facts in favor of a greater drama of place and class. Nor is he even quite an American Surrealist like George Tooker, for whom terror lurks behind every pillar in the subway. He is most definitely not a poet, a chronicler, or a formalist like Berenice Abbott, for whom a subway newsstand becomes a sea of histories and texts.

Like a good cartoonist, he allows himself a few screaming words, like Extra! or Why Not Use the "L"? And, true to its mission, the New-York Historical Society presents the small show as a chronicle of his decade and the American modern. It includes most of the artists mentioned here, along with familiar works from the Whitney and the Met. Still, the hero of "Swing Time" is not much of a swinger, even when he come out swinging. His subject is not the tragedy or heroism of the Depression, but the spectacle. Where Paul Cadmus paints sexual encounters for sailors at Coney Island as acts of aggression, Marsh is caught looking.

"Real/Surreal" ran at The Whitney Museum of American Art through February 12, 2012, while a selection of David Smith ran upstairs. "Swing Time: Reginald Marsh and Thirties New York" ran at the New-York Historical Society, through September 1, 2013.