Art Again

John Haberin New York City

After Covid-19: A Cautious Reopening

So that is what it is like to look at art again. No, I had not forgotten, even after fifteen weeks of shuttered exhibitions. Neither, I know, have you.

Still, on my first day back in the galleries, almost everything came as a welcome surprise. It also had me more aware than ever of the dearth and uncertainty that remain. Now if only, I kept thinking, the surprise will last. And then, as I came back to earth, I could learn from asking why I was ever surprised in the first place. What does that say about seeing art live? And what does that say about art after Covid-19, when the summer's warm welcome wears out?

A stake in forgetting

Make no mistake: those who display art had a stake in your forgetting. They had too much riding on private dealing rather than "brick and mortar" merely to survive. They had too much riding as well on the credibility of virtual fairs, virtual exhibitions, and shuttered museums. And many chose not to return, at least not right away. One brought Joan Snyder to its online "viewing room" the very day that a handful of others opened to the public. Martos, Microscope, Carriage Trade, and Cristin Tierney continue to roll out old film and innovative new media.

Then again, what should appear on reopening, and what now defines the gallery? Exhibitions closed prematurely in March, so it is only natural to extend them rather than to introduce something new. By now, too, galleries are moving into the banality of summer group shows and summer closings. After so many weeks, shuttered doors are now, by a bitter irony, just business as usual. What, then, can make up for what was lost? Who can compensate artists with planned fall shows crowded out by delays or spring shows that will never take place?

Still, on a long, casual tour of the Lower East Side and Tribeca, art did not look any less real (and some of these links here will take you to a fuller review). I could experience Serkan Ozkaya and Joseph Beuys together as an installation, as I never could online—and walk on it, with a spring in every step. I could encounter large photos of women by Ruben Natal-San Miguel in a mass rather than as click-through images, in the very next room. Now I had to ask what I know about the women in my life, too. Prepping for my visit, without a gallery guide or SeeSaw app for help, I was ready to dismiss Gaku Tsutaja as cartoons. At floor to ceiling scale, her "Spider's Thread" seems more mysterious—and its reliance on ink on gesso a lot stranger.

Even a modest change in scale can make a major difference. Online, the cryptic symbolism of Karla Knight may look as fussy as many a graphic novel. In person, it takes on the space of painting. Online, too, colorful interiors by Hilary Pecis might look like a family album on Instagram without the cats. In paint, they exist not in a day's posting, but an eternal Sunday. Upstairs with Curtis Talwst Santiago, his multicultural heritage takes on a literal third dimension, both inviting and barring entry, much as at the Drawing Center before the lockdown.

I headed back downtown the very next day, for artists whose very intentions turn on their media. Benjamin Butler and Bastian Muhr, both German painters, share a small room. Their respective green monochrome and curved black shapes look stark and cryptic. Yet they bring a painterly touch to a rebirth of Minimalism, and how else to do that but in paint? Spread over four canvases, like fence posts, Butler's smears even resemble wood grain. His title, Green Fourest, also puns on deep, dense spaces and poured paint.

Stains and spills are back in earnest in the same gallery's larger room, with Pamela Jordan left over from the spring. Her bright and dark colors flow easily into one another, with little respect for their ground. They also play against the firm edges of her shaped canvas. Often curved, the pieces fit together, but with seeming gaps and protrusions. They play on contrasting markers of formalism and process—of action and abstraction. Mythmaking by Kyle Staver is back as well, even more exuberant and ingenious.

When digital becomes physical

Even now, so much else is not back. Phase 2 of the city's reopening allowed retail and many offices to return on June 22, and most but hardly all did. Galleries have been more cautious still. They may have health concerns, or they may just not sense a demand. Visitors often abandon New York as summer nears its end. Now those who could afford to leave were already gone.

Galleries might have envied stores that went through phase 1, of online orders and curbside pickup. Now if only they faced that kind of demand! Some boasted of reopening, but most often by appointment only—almost entirely so in Chelsea, which remains partly shuttered until fall. (Some will try to accommodate you if just show up.) Surely a gallery enters phase 2 along with others, as a business and not a spoiled child. The reality, though, gives new meaning to "he's just going through a phase."

Galleries might have envied stores that went through phase 1, of online orders and curbside pickup. Now if only they faced that kind of demand! Some boasted of reopening, but most often by appointment only—almost entirely so in Chelsea, which remains partly shuttered until fall. (Some will try to accommodate you if just show up.) Surely a gallery enters phase 2 along with others, as a business and not a spoiled child. The reality, though, gives new meaning to "he's just going through a phase."

I was delighted that paintings as illusion, fabric, and collage by Rebecca Morris remain on view from so many weeks ago, with Anna Ostoya coming up. It was to take another week, though, before they no longer stood in the dark as I passed with no one to see them. Could the choice not to open reflect a dealer's vision? On my very first stop, a director spoke eloquently and often of how only a personal encounter will do. I was to hear that theme more than once again. Maybe closed galleries are just facing up to financial realities—or maybe they do not share the vision.

Was she calling for a dated view of art, as object and as gesture, and am I? Snyder is old enough to have known both as a painter, but her gallery was no less boarded up. Should I call my very exhilaration into question? Any other day, Tsutaja and Pecis might have appeared far more lightweight. Tsutaja's drawing still seems awfully obvious, her narrative about the Manhattan Project obscure. Those eternal Sundays may verge on Sunday painting—or they may last.

I will just have to revisit once or twice to know. Still, the initial surprises are worth remembering. Sure, expression and formalism needed a challenge from diversity and deconstruction. In turn, though, a distrust of surfaces has a prudish history. Plato would have banished Jackson Pollock from the Republic, had he not crashed into a tree first. Politics is more urgent than ever, after mass protests and in an election year, but it can still embrace art.

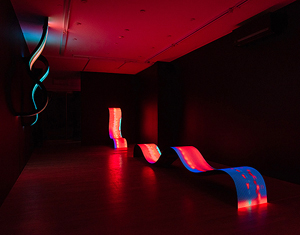

Galleries will in time reopen, apart from those that have, sadly, closed for good. And the very idea of the virtual must have room for the likes of Daniel Canogar. His LED screens take the shape of waves, as "Billows," rolling out from the walls and across the floor. Their colors roll out electronically as well in loose parallels, much like Jordan's stains, while staining every corner of the room. Pleasures can thrive in physical or in digital form—or in both. And then they persist in the life of the mind, waiting for you to look again.

Postscript: a warm welcome

It has taken a global disaster, but I have become respectable. Even Chelsea dealers and curators have been stepping out from the back room or from behind the desk to talk about the art they love. As galleries reopen (cautiously), they ask if I have any questions and even thank me for coming. And well they might after months of silence, for they must be as restless as you and I. Well they might, too, for I could still have many an exhibition to myself, even on an opening day. It is a welcome experience, but it brings home the uncertain fate of art.

Not everyone, I realize can expect the same warm welcome, even with an appointment. Not that I have become any more respectable as a critic. (Oh, if only I had overcome my shyness to promote myself in the 1990s, when I was the only arts Web game in town.) I am, though, a white male with increasingly white hair, enough to pass without trying for a buyer. Diversity has become a priority for the arts, but stereotypes persist. Black lives matter, but racism is by no means a thing of the past.

Not that dealers are wrong to hope for collectors. Who without a passion for art would hit the galleries in the heat of summer and the depths of a pandemic? And the same reasoning should have anyone fearful for the months ahead. The Met in July announced its reopening in late August, but will anyone come? When I reported on gallery failures and museum finances back in April, I never dreamed that the health crisis would only deepen come summer, and one can only imagine the toll by the time of museum reopenings. This is not just a global disaster, but a national one, and its name is the party of Donald J. Trump.

Maybe some will come, but can they expect to get in? The Met may have been negotiating all along with New York behind the scenes, and it may count on its weight as a huge and beloved institution. Still, the state showed not a hint of opening indoor spaces until caving, with serious restrictions, close to the last minute. An upscale gallery welcome is just as likely to include taking your temperature and asking whether you have shown symptoms or had contact with the virus. Never mind that temperature is a poor indicator or that those who go outside with the disease are not heading for art. They are far more likely to be impoverished workers and people of color afraid of losing their job.

Many other galleries just take your name and how to reach you, and why not? Contact tracing is badly needed, and America is once again behind the curve. Still, you may object, busy stores do not take anywhere near the same precautions, and galleries really are empty—although evening openings as social events are a thing of the past. You may be tempted to wave your arms in front of the dealer to show how well you two are social distancing. Even the Met was always much like an outdoor public space, where people pass for barely a moment, and it will be again when museums reopen, with Amanda Williams at MoMA cordoning off the chairs. As for smaller institutions, like the Bronx Museum or SculptureCenter, you could have them to yourself any day of the week.

I suspect that public officials just plain have little experience with the arts, as opposed to sports and mass entertainment. I suspect, too, that they fear for bad press—just as New York City's mayor threatened to close parks after a single embarrassing photo in May. (Now the governor has shut down drinks without food, even alone at tables, after some young adults made a block in the East Village into a block party.) I hope that the arts can extend that warm welcome. Still, the plight of galleries, museums, and artists is going to get a lot worse before, if ever, it gets better. Will restrictions that seem so easy to meet in summer mean long lines and missed exhibitions this fall?

I returned to the galleries starting June 25, 2020. Joan Snyder ran at Canada online through October 10 (later entering the gallery), Serkan Ozkaya and Joseph Beuys with Ruben Natal-San Miguel at Postmasters through July 31, Gaku Tsutaja at Ulterior through August 9, Karla Knight at Andrew Edlin through July 11, Hilary Pecis at Rachel Uffner through July 3 and Curtis Talwst Santiago through September 10, Benjamin Butler and Bastian Muhr with Pamela Jordan at Klaus von Nichtssagend through August 8, Kyle Staver at Zürcher through July 24, Rebecca Morris at Bortolami through June 30, and Daniel Canogar at Bitforms through August 16. Again, many of these receive fuller reviews in related articles, as do Covid New York, art after Covid-19, museums after Covid-19, "virtual exhibitions," and virtual art fairs.