The Most Toys Wins

John Haberin New York City

Pace and Gallery Expansions

Alexander Calder and Andrew Ohanesian

If wealth in art seems unevenly distributed in the extreme, so is global capital. And the stratification in both comes at a terrible cost.

Consider, though, another explanation. A certain class of collectors may just play by different rules or, better yet, a different rule: he who dies with the most toys wins. How else to explain Jeff Koons, who has succeeded beyond anyone's wildest dreams by making just that. For a certain class of dealers, though, the rule is playing out a bit differently: he who dies with the most floors gets to fill them,  and for now Pace gallery is winning—even as Andrew Ohanesian is tearing up a gallery and taking the rules apart.

and for now Pace gallery is winning—even as Andrew Ohanesian is tearing up a gallery and taking the rules apart.

The most floors

Of course, she can die with her toys, too, although naturally the biggest egos and some of the worst excess lie with men. (Just wait until Mary Boone gets out of jail for tax evasion.) Hauser & Wirth, too, is on its way to a new building in Chelsea. Founded in Switzerland by a woman, her husband, and her mother, it already has three floors for exhibitions right next door in the former Dia:Chelsea, with more on the Upper East Side and abroad. Meanwhile I can only look forward to Paula Cooper's one-story flagship after renovation a block away. She is still my personal hero for her accessibility and loyalty to artists even now, long after founding the very first Soho gallery.

David Zwirner aims to consolidate its mammoth operations as well, while Gagosian settles for expanding its largest space into the adjacent building. A horizontal move makes perfect sense for a global empire. Still, Pace beats them all to the punch, with an eight-story building by Bonetti/Kozerski Architects. It opened in September with a scary six solo exhibitions, and it has space on top of that for a research library, a performance space, three floors of offices, an outdoor sculpture terrace, and a smaller terrace just for the view. That performance space, Pace Live, has panoramic views of the greater wealth of Hudson Yards. And one of those solo exhibitions features Alexander Calder, whose wire Circus, completed in 1931, already made art into toys.

I know, you just love to hate the winners, with good reason, based on who loses out. That can include not just artists and dealers who never make it, but also those caught in the middle as they struggle to reopen and try to keep innovation alive. (The parallel again to global capital, with dire poverty but also stagnant wages and rising rents for the middle class, is obvious.) Still, the top tier can afford to contribute now and then what others cannot. That includes Gagosian's shows of late Picasso and Zwirner's current looks at Ray DeCarvara, the African American photographer, and Anni Albers as a weaver and a woman. If nothing else, the bar at Hauser & Wirth, designed by Dieter Roth, and its bookstore would make it a place to hang out.

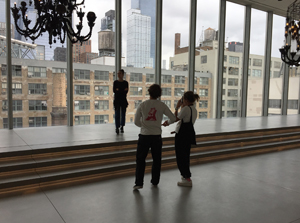

Pace, though, is not just throwing a party. It mixes in a living African American, Fred Wilson, and two women largely new to me, Yto Barrada and Loie Hollowell. Wilson displays his ornate black and white chandeliers, in the space for Pace Live—as if to comment on the spare interior, the nasty towers out its windows, and race in America. On opening day, a staffer sat there in an old-fashioned upholstered chair. Barrada, from Morocco, applies gray pastel swirls to one wall of the library, as backdrop for smaller works in light colors. Hollowell recalls Hilma af Klint a century ago, with painted foam that brings her symbolism and spiritualism into the third dimension.

The gallery does not feel the need to dignify itself with long-past masters or the latest thing. It distances itself from commercialism with the choice of a library rather than bookstore, even while running a successful commercial operation. It has at last rid itself of the primitivism of Pace Primitive, renaming a space Pace Oceanic and African Art. Half a dozen examples play off against epic abstraction by Antoni Tàpies and Adolph Gottleib. One can forgive calling a small show of portraits and dancing nude self-portraits by Peter Hujar "Master Class," as if to turn the poignant and provocative photographer, who died of AIDS, into the old master he never lived to be. (The title comes from an actual class he took with Richard Avedon and Marvin Israel, who drew back at Hujar's shoving a banana up his arse.)

One can forgive, too, the gallery's self-appointed old master, with the self-proclaimed grandeur of La Grande Cour, Normandy. David Hockney applies ink on paper for his first impressions of a new studio in France, unfolding on two walls and in an accordion book. Will Pace succeed, as it hopes, as "more an arts center than a gallery." How will its sculpture terrace serve, now bare, gallery regulars like Louise Nevelson? Already one can see its architecture as embodying its good intentions. One can also see how deftly Calder plays with toys.

Finding a balance

From the outside, big boxes of reflective aluminum recall SANAA's New Museum on the Bowery, while its height and windows accord with the glass condos to all sides along the High Line. Its intended purposes also recall The Shed at Hudson Yards. Yet it is not just showing off at the expense of art. At street level, one first encounters a surface of volcanic black. Pace wants to be classy, it announces, but not crass. For those not classy enough, will that suffice?

Facing a hefty lobby desk, one might fear not. I half expected someone to ask whom I was visiting, but the staff hardly looks up except to welcome questions. (It would have flattered me, though, had Hockney in person told them to expect me.) Galleries are less than imposing as well, notably smaller than Pace's last space up the street. Like everything else, they are also reasonably welcoming. A freight elevator shares an alcove with two passenger elevators, so that nothing takes place behind the scenes.

As architects, Bonetti/Kozerski, have other touches above stand issue as well. Walls can allow single rooms or a maze of them, and people seem comfortable using the library. Broad steps up to the windows double as seating for Pace Live. Sepia tiles on the terrace soften the aluminum, much like the volcanic black. They bear striations like tree rings, and pebbles litter the spaces between them. There are adequate bathrooms and a drinking fountain on the terrace.

The maze for Alexander Calder delays encounters with the show's chief subject, Small Sphere and Heavy Sphere from 1931. Its unfolding withholds an ending even as it provides context. Quotes from Jean-Paul Sartre, the philosopher, and Jimmy Durante, the comic, describe Calder as capturing motion rather than representing it in sculpture. His encounter with Piet Mondrian then sets him to embody motion in Modernism. Two circus-themed sculptures start him playing with toys, with not a Jeff Koons in sight. Last, a selection introduces work in motion and in space, with spheres.

The maze for Alexander Calder delays encounters with the show's chief subject, Small Sphere and Heavy Sphere from 1931. Its unfolding withholds an ending even as it provides context. Quotes from Jean-Paul Sartre, the philosopher, and Jimmy Durante, the comic, describe Calder as capturing motion rather than representing it in sculpture. His encounter with Piet Mondrian then sets him to embody motion in Modernism. Two circus-themed sculptures start him playing with toys, with not a Jeff Koons in sight. Last, a selection introduces work in motion and in space, with spheres.

The trick to the central work is a hidden motor, but even more a sense of balance. A short pole hangs off-center from a string that gives the work its central axis. The lead sphere at one end of the pole, in red, and a small white sphere at the other keep the pole parallel to the floor. Both hang at the end of long strings, too, so that you may have to search for them. The red sphere swings in a narrow arc, like a pendulum, while the white sphere's distance from the axis allows it to fly every which way. It has a lot in its shifting path.

It can bang on a can, for the work's audible rhythm, and land in the can every so often so that someone has to take it out. It can run into a row of bottles, like a machine to take them down. Literally striking, the work might seem poised for self-destruction, like those of Jean Tinguely and Peter Fischli and David Weiss, but it keeps finding a new and gentler life. Later, Calder settled into a larger scale in red, as the public face of Minimalism and urban plazas, at the expense of surprises and a lighter touch. Can Pace sustain its own lighter touch? Just pray that it does not lose its balance and run short of toys.

Like they never left

Amid the wealthiest of galleries expanding into megastory multiplexes, amid the buzz of outsider art and emerging artists, amid biennials and art fairs—amid it all, one can easily forget. Forget, I mean, the midlevel artists and dealers that sustain and revitalize art. Forget the ones that vanish seemingly at their peak, their promise to reopen elsewhere never sustained. Forget the ones that become private dealers or art advisors, only to serve the not so precious few. Forget the ones that do turn up again when and where one least expects it. For Pierogi, it turns out, that means exactly when and where it left.

Few expected the gallery to give up on Williamsburg, where it initiated an art scene—and where it still maintains a second space as the Boiler. Few would expect it to close its comfortable home on the Lower East Side either, after already posting its fall season. Just a half hour before its announced opening, though, I almost turned away. Someone had papered over its windows and posted an all too familiar sign for "retail space for lease." (The real estate agents and their phone numbers are real.) Inside, the space was gutted and devoid of life.

The gallery name on the window was still legible, though all but scraped away—an intriguing irony after a spring group show there on the theme of "Under Erasure." I had seen art before papering over the gallery and a show as itself "Under Construction." Andrew Ohanesian covered this very gallery's original location with scaffolding, in 2014, and remodeled for a week of Bushwick open studios, while the dealer served hot dogs, but not like this. Still, the door was open, and I ventured inside, wondering if I belonged. To be honest, it took a phone call first, but I should have had my suspicions. Spaces still up for rent do not often begin reconstruction.

Ohanesian himself has begun, as 5000 SqFt WILL DIVIDE, and just a few minutes later we would have had plenty of company. As it is, he has cleared away walls but left the tools of his trade to every side. Ladders, hand trucks, you name it all lie neatly stacked or up against the wall. Work crews do not often take such care between shifts, but (like almost anyone with anything to do with art) I have done that kind of work, and I felt a kindred compulsive spirit. He has not nearly enough Sheetrock to finish the job (yes, another clue), but he is not just taking things down. He is, as the gallery writes, "building out."

Sure enough, the back space looks the same as ever, with art on the walls, offices, and a reasonably warm welcome. This will teach me, I thought, to wait on an opening for company and the chance of a drink, but I had a busy evening ahead on the first week in September. Yet Ohanesian is questioning the very premises of an opening, in more ways than one. What does it take to persist in the face of gentrification—and are artists to blame, as some have said about the Lower East Side and Williamsburg before it for the condos and prices to come? The show works as conceptual art, spectacle, performance, and deceit. Still, it has a lot to paper over.

Sarah Sze has papered over windows, too, but with sloppy screen prints, and left paint supplies just inside the door. She brings more work tools to a back room in Chelsea and spatters still more white paint on the floor upstairs. As ever, her heart is in the studio practice and the chaos, now updated for high tech. A wire screen picks up her reliance on line, but here lined with more than a dozen mobile devices in action. Yet the tidy half circle around a huge white painting, marking the inner border of the mess, shows her mixing calculation with her chaos. Like her model apartment in 2006 across from the Plaza Hotel, itself largely converted to upscale apartments, any reference to real estate is purely coincidental.

Pace opened its new building on September 14, 2019, with Alexander Calder and others through October 26. Andrew Ohanesian ran at Pierogi through September 29, Sarah Sze at Tanya Bonakdar through October 19. Related reviews look often at art and money, but also at Alexander Calder and Calder mobiles.