Abstracting Away

John Haberin New York City

Abstraction from Nature

JP Munro and Ilana Savdie

When a summer group show takes as its theme "Abstraction from Nature," you can only wonder: how could no one have thought of this before? It makes that much sense.

You may wonder, too, though, what so broad a theme could possibly leave out. With drawings like these, the answers lie in the details. This is art from an active eye and hyperactive pencil, brush, or pen. Not that it is the only way to go. JP Munro works in big gestures between abstraction, nature, and myth, while Ilana Savdie treats abstract painting as quite a carnival. So how about a cheer for those refuse to play mythmaker?

Nature on the subway

It is not just a cliché to compliment art after nature as approaching abstraction. I felt the urge just this month in Tribeca, with JP Munro. It is just as common to speak of abstract art as abstracting away. With Susan Vecsey in Chelsea, horizontal bands of close colors, often blue, hint at the horizon, sky, or sea. The gradual narrowing of one band is more suggestive still, of a road in linear perspective running alongside nature into depth. Back when, critics who disdained realism might make an exception for landscapes by Fairfield Porter—and, like Robert Rosenblum, find an antecedent to Abstract Expressionism in the Hudson River School and Northern Romantic tradition.

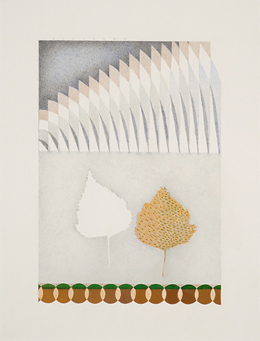

The New York School had no trouble leaving New York, at the very least in summer. Painters then could afford the Hamptons (and maybe a loft in Soho). The nine artists in "Abstraction from Nature" are not so lucky, but they still find nature everywhere they look, starting in the city. Abby Goldstein speaks of urban walks, Sarah Walker of collecting fallen leaves. Chris Arabadjis does his drawing on a two-hour commute. But then I run into flowers by Nancy Blum whenever I catch the subway, for she has tiled the nearest station.

When it comes to life in the subways, you may think first of germs. Arabadjis invokes instead tree rings, whirlpools, rock formations, and mycelia—the threads in fungi. If that sounds strange, they are all networks, tilings, or eddies. They are also rule-based, like his drawing. This Lower East Side gallery has a commitment to geometric abstraction, like that of Don Voisine, Gary Petersen, and more from past reviews than I can list here. Yet it also has a genuine fondness for surfaces, signs, and symbols.

That can mean obsessive patterning, of a kind that cannot help disrupting the pattern. Laura Sharp Wilson speaks of Defying a Brutal Art. It can lead to a search for optical activity as well, akin to Op Art, like Wilson in acrylic and Walker lending nature her electric color. Webs by Katia Santibañez seem to vibrate, as does paper itself for Marian Williams. Her pen adds a shimmering blue.

What they do not do is to hover between nature and abstraction. Almost everything here falls within one or the other. One will just have to take Santibañez at her word that her abstract webs look outward to spiders. Blum in fact produces two bodies of work for the show's twin inspirations. Pencil weaves through her black paper or radiates outward. White clay butterflies hang high on the wall.

Their shared strength may lie less in the image, real or abstract, than in the artist's hand. Jessica Deane Rosner could be denying both, with the appearance of collage in pencil, ink, and acrylic. Others, though, dedicate their work to the medium itself, like Katia Santibañez with her vibrations and Denise Sfraga with colored pencil. And that returns to a nagging question in art today. As painting proliferates and genres lose their meaning, what does that leave for abstract art? After all these years, the media may still be its message.

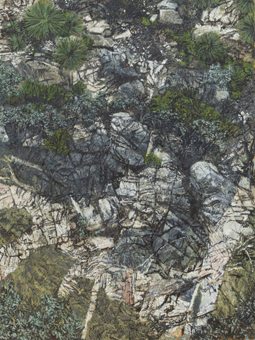

Laying it on thick

JP Munro does not have to paint all that thickly. Things for him are thick enough as they are. His landscapes place one right in the middle of them, too, with a point of view so close that one could reach out and touch. The temptation is real at that, for the rocks and vegetation are that rough and that vivid. This is what Gustave Courbet meant by realism in the mid-nineteenth century, give or take Courbet's view into depth or a way out, into the light. What they are not is alive.

They may seem alive, when bare rock has a life of its own, but not to Munro. What I took to be rivulets coursing through them are dead branches. What I took to be wild greenery is dead weeds. It is hard to know whether to celebrate or lament their death, but then the viewer is an intruder, too, quite as much as any invasive species. Still, the overall tonality is lush and green. Other intruders lurk here and there as well, adding accents of brighter colors and a further puzzle of just what they are.

They may seem alive, when bare rock has a life of its own, but not to Munro. What I took to be rivulets coursing through them are dead branches. What I took to be wild greenery is dead weeds. It is hard to know whether to celebrate or lament their death, but then the viewer is an intruder, too, quite as much as any invasive species. Still, the overall tonality is lush and green. Other intruders lurk here and there as well, adding accents of brighter colors and a further puzzle of just what they are.

One wants to reach out for another reason, too, to get a grip. The close point of view leaves nowhere to stand. One cannot say whether one is looking down, on treacherous ground, or at a rockface in reflected light. But figures do have a place to stand in a second series, of Norse or Slavic gods and heroes. Some of those paintings are dense as well, but another has room for several figures and a story set at Versailles, in the Hall of Mirrors. I could not swear who is enlightening whom.

Munro, who appeared in 2007 in a show called "Defamation of Character," flattens an angry woman by framing her in a doorway at an odd angle to the painting. A happier god stands in a radiating oval, like a revelation. Do the series hang together—apart from literally, without so much as separate walls? The gallery sees them as united in the sense of polar opposites, which could excuse anything. Still, Courbet had his figure paintings, too, including the notorious female nude with an open crotch. Her pubic hair echoes the French artist's rocks and vegetation.

Munro's figures are less obviously challenging or sexist. I worry less that the figure paintings do not fit than that they are a bit silly. In every way, they lay it on thick. Pagan or not, they also draw on classical sculpture and Renaissance art of the life of Jesus. Still, they add density to an already dense show. The gallery has a fondness for painting as installation, and the up-close views fit right in.

It used to be conventional to describe landscapes like these as indeed approaching abstraction. In the project room, Jessie Henson goes all the way, but with her own unexpected textures. She, too, has two series corresponding to light and dark—fields of color like stains and darker colors with slim traces weaving through. Both, it turns out, get those effects with gold and thread amid polyester on paper. They look a bit too familiar, but she works with an industrial sewing machine. Sometimes it pays off to lay it on thick.

The museum carnival

Ilana Savdie paints big, with irreverent abstractions that span the rainbow. So do her themes, from gender to global power, in what the Whitney calls a "riotous excess." Raised between Colombia and Florida before settling in Brooklyn, she is herself a model of diversity. In other words, just another day in the galleries, only this is the lobby gallery at a major museum. It has me thinking about the place of contemporary art in the museum. It has me thinking, too, about what to expect from abstract painting today.

This could be the most fun I have had in ages in a hoary institution like this one. If not, it is entertaining enough, and Savdie will try anything once to make it so. She counts among her inspirations the carnival in Baranquilla, her birthplace in Colombia, and carnival is as good a description of the work as any. It takes its intensity from stains blending into one another and raised fields of acrylic and oil dotted with wax. Flat, hard-edged colors have biomorphic outlines that hint at still more. When a more regular element appears, in paired stripes, they earn that name Barnett Newman gave to his verticals, "zips."

Blue spills across some paintings like sky or sea. Others have a paler color at center, like a profiled face or a chasm. It could be pulling one into something dangerous or pushing one out and away. They would be at home in more than one downtown gallery with a taste for abstract art as installation. Sure enough, Savdie opens with drawings in pen and acrylic, in black on white, hung against wallpaper or wall painting of her devising. It depicts tight rows of fuzzy red balls interrupted by fleshy blobs, like the artist's hand or bare butt.

As for the imagery, I could make out a hand or two, its nails extending to the point of claws, but little more. One painting claims to include a trickster from Francisco de Goya and his graphic imagination, another a half human, half elephant, and half monkey from the carnival. (If that adds up to more than one, think again of excess.) They sure tricked me, who could not see either one. Nor could I see the loftier themes of which the curators, Marcela Guerrero and Angelica Arbelaez, make so much. Savdie gets to stand for sexual diversity and Latin American art today.

If that threatens to devolve into a formula, this could indeed be just another day in the galleries. The Whitney, to its credit, makes the lobby gallery free and open to walk-ins, although without access to a bathroom, much like Chelsea galleries a few blocks away. The wall with works on paper opens onto a modest gallery at that, with room for fewer than a dozen paintings. One can almost imagine a dealer's desk in the narrow entrance. It could serve as a model to other museums willing to offer reasonable access. Instead, they are risking their mission and their finances to appeal to collectors of contemporary art.

That includes the Frick and the Morgan, although both have done so with flair. Sure, the Whitney has always spanned the historical and contemporary, only starting with the Whitney Biennial. Sure, too, private galleries face the same dilemmas. Is there anything left for abstract painting now that anything goes, beyond today's taste for elusive imagery and the artist's hand? Can one see half the subtext claimed for their exhibitions as well? I cannot swear that Savdie adds up or stands out, but she is still putting on a show.

"Abstraction from Nature" ran at McKenzie through August 18, 2023, Susan Vecsey at Berry Campbell through August 11, JP Munro and Jessie Henson at Broadway through July 28, and Ilana Savdie at The Whitney Museum of American Art through October 29.