Shaping the Square

John Haberin New York City

Don Voisine and Angelika Schori

Remember geometric abstraction from nearly half a century ago? For Frank Stella, it could take flight like an exotic bird. For Elizabeth Murray, shaped canvas could explode into scraps from everyday life. It could have the craftsmanship and rigor of Charles Hinman, the casual but vital cool of Richard Tuttle, or the defiance of its own logic of Robert Mangold. For Ellsworth Kelly, it need not even depart from the rectangle.

It might seem newly relevant, now that painting is back, but less as formal exercise than as a hybrid of styles and media. I keep coming back to that hybrid, not solely with shaped canvas and its heirs. I have caught art between painting and sculpture or challenging the opposition between exuberance and geometry. Still other artists, though, are putting geometry through its paces much like Stella, including Don Voisine strictly within the rectangle and Angelika Schori on both sides of the picture plane. Voisine looks that much more provocative a decade later.  Their art does not need shaped canvas to reshape the rectangle.

Their art does not need shaped canvas to reshape the rectangle.

Cleaning house

Don Voisine shapes painting the old-fashioned way, with paint. I almost said "the hard way," but that would sell short some truly pioneering artists. No one is going to match the rigor, energy, and humor of Frank Stella and Elizabeth Murray with their actual shaped canvas, and that does not count the sheer feat of its construction. Even after seeing a pioneer of shaped canvas, Charles Hinman, with work in progress in his studio, I still hardly know how he does it. Come to think of it, the craft behind a Renaissance tondo, or round painting, deserves some respect of its own. Voisine, though, pares oil on wood back to basics, while keeping things in motion.

His hard-edged stripes run parallel to the picture's edge, much as for Susan English or early Stella. The generally modest size of his panels gives added breadth to the stripes—and added weight to Voisine's care in effacing his brushwork when he wishes. They may reach right to the edge, although thinner bands may instead provide a buffer, much as Stella's brush stops short of filling the canvas. The colors of the thinnest bands, including pink and olive, play off against the underlying surface and each other. Thicker stripes run diagonally, merging into still broader fields of paint. Stella departed from the grid with his last paintings to exhibit an unquestioned formalism, the Irregular Polygons of 1965 and 1966.

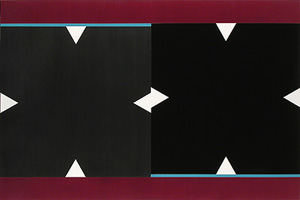

Voisine, though, is not giving up on the rectangle. More often than not, he barely departs from a square, and the diagonals owe their direction to nothing more than themselves and each other. They stand out at a painting's center, between paired horizontal or vertical bands. They cross or abut one another as well, like an X in the process of both thickening and coming apart. They come in red, white, and, most often, the color that provided Stella with his own breakthrough, black. They lend the image its sense of motion, while their very breadth helps to reinforce its stability.

Is it insulting to praise these paintings as "clean"? That sounds almost prurient, but the clarity is enlivening, just as with Minimalism. It may also sound as if loose brushwork, in contrast, is just plain dirty, as part of the very revival of abstraction, legitimized by slick shows like MoMA's "The Forever Now." Sometimes it seems as if anyone can throw paint around, including painters who pride themselves on not settling for conceptualism or irony. That still leaves a long lineage of simplicity but unpredictability, going back at least to Ellsworth Kelly and Robert Mangold. If it can leave me cold, some days I really miss it.

Voisine stays still closer to the grid, and that contributes to the logic of stability in motion. He keeps experimenting, but within the bounds he has set himself. He is working more with contrasts between matte and glossy areas, much as Ad Reinhardt works with contrasting tones in black on black. His thin bands are becoming more prominent notes of color. He is also paring things down still further, as in his last show, with some paintings restricted to cream or to black. In all these ways, he retains the motion of shaped canvas and the stability of oil on squares of wood.

I would call them subtle, like Pete Schulte at the same gallery, but that, too, sounds insulting. I first encountered Voisine along with Gary Petersen in group shows, as a kind of Bushwick Neo-Neo-Geo. A revival of Minimalism is common elsewhere these days, too, in both painting and sculpture. It can seem like just one more formula among too many others, yet another example of what Jerry Saltz has called "derivative art-school abstraction." Yet artists can still shape painting with minimal means and an appreciation for paint. Never mind that Stella himself gave up long ago.

Symmetry breaking

Don Voisine is getting messier. It may seem like sacrilege coming from one of the cleanest painters in town. Few have shown off as well how much energy a design can acquire just by cleaning up its act. Voisine keeps returning to diamonds, rectangles, and squares, framing them carefully with color, with the spotlight on the image center. Sound boring? You got tired of that, I know, in the 1960s, when what you see is what you got. For him, though, symmetry is itself the key to symmetry breaking.

When Voisine showed exactly ten years ago, he brought to mind the shaped canvas of Frank Stella and Elizabeth Murray in the 1960s, without once departing from the rectangle. He evoked Stella's Irregular Polygons without the least irregularity. All it took was oil on panel, with plenty of blue, black, and white. Setting familiar shapes on their side, in concatenation, and treating some as accents converted triangles into arrows in space. Framing strips of oil at top and bottom absorbed their pressure. It brought out the Neo in that New York Neo-Geo.

Now he all but gives up the balance, but not altogether the symmetry. This is his self-conscious revision, as "enact/re(d)act." The borders remain, as notably broad as ever, anchoring the whole. They retain their unusual colors as well, including maroon and orange. Some are off-white, with a tempting translucency, making them thicker for the eye to penetrate. Squares may gather that much further to the center of a composition, as diamonds.

Titles suggest a combination of playfulness and restraint. You are at Poolside for the summer, with a Quip. This is Tranquil but Shearing all the way Through. Juxtapositions play a greater role throughout. Triangles become taller, slimmer, and slightly tilted, like metronomes in motion. Variations on black itself come into juxtaposition, challenging you to decide whether in fact they differ.

You could end up thinking that he has ruined the whole show, and he could be fine with that, too. Such are the risks of abstraction. Such, too, is the virtuosity of opaque color and translucent black. I could not say myself whether he had put his past to rest or built on it splendidly, but I spent a long time enjoying the effects. Besides, Stella has long since made a mess of the whole painterly show himself. Still, the focus is on clarity, in sorting out a thinner rectangle or a thicker X.

There is, as ever, plenty of decent abstraction out there. Not all of it need be woven, as a textile. Take your pick. Or stick to abstraction as a metaphor—or a metaphor as abstraction. A map is an old one, and Lena Henke maps Manhattan. It looks ever so handmade, like a relic, as a nostalgic tribute to the city. So what if you cannot pin down just what about New York Henke is mapping, least of all its art?

Running the light

Angelika Schori calls her show "Light Touch," and for all that her work bears down of its own weight. Schori rings the changes on detaching painting from its stretcher, while still identifying it with its support. In each series, paint runs right to the edge, much as for Minimalism. With some, diagonals run casually every which way. With others, canvas laps into the room cut, crumpled, and damaged. Yet the more material they are, the lighter they get, and the more the light emerges from within.

Lightness might be on the artist's mind just from dropping in on Orchard Street. Her gallery called an earlier show of Michael Rouillard "Lighter Still," as if he had somehow seen Schori's work and responded in advance. She has that light touch most obviously in mere canvas, holding itself up to the wall as best it can. In a second series, canvas peels away and hangs down from the center of a rectangle on stretcher, as if sticking out its tongue. The whole composition might represent a TV set from a clunkier age. The lightness of tone, though, matters less than the lightness or weight of materials.

Lightness might be on the artist's mind just from dropping in on Orchard Street. Her gallery called an earlier show of Michael Rouillard "Lighter Still," as if he had somehow seen Schori's work and responded in advance. She has that light touch most obviously in mere canvas, holding itself up to the wall as best it can. In a second series, canvas peels away and hangs down from the center of a rectangle on stretcher, as if sticking out its tongue. The whole composition might represent a TV set from a clunkier age. The lightness of tone, though, matters less than the lightness or weight of materials.

Both series could have a point of reference in Arte Povera, with all its violence against the work of art, but with much less to prove. They are also about light in the sense of color—and of letting color speak for itself. Schori has painted the back of the canvas a different color, and the very damage allows one to see it. Again like artists of the 1960s, she has nothing to hide. Here what you see is very much what you get, twice over at that. Yet it matters, too, that one never sees all of it at once.

The third series is the most consciously shaped, but also the most luminous. Here she works on powder-coated steel, each piece a variation on the rectangle. Several pieces hang together from a pin, like steel for Erin Shirreff. Their contrasting diagonals also push away from the wall, like stripes for Frank Stella in the 1970s. Their pure white matches the white of the wall, but with a greater glow. It arises not only from the reflective powder and metal, but also from bright color on the edges and backs.

Variations on Minimalism keep coming, but without the self-conscious grandeur of geometry back in the day. Tondos from Pamela Jorden have wisps of paint out of Robert Delaunay and Sonia Delaunay, sometimes sharing half the field with black. Adam Winner has even more in common with Schori. For "Scratchpad," some paintings stay only white, as for Robert Ryman, their torn edges attesting to their making. Others have the concentric rectangles of still earlier Stella, in black or white, with the same care to leave space between them so that its brushwork stands apart. Here, too, though, the thick stripes take on color from the underpainting that they reveal.

Somehow painting has outlived the death of painting. Galleries feel the pressure to insist on it at that, by boosting older artists who may have missed their fair share of the action. In her "verb paintings," Lee Lozano took as her titles active verbs—like Pitch, Slide, Lean, Swap, and Cram. Their shaped canvas fits together into rectangles that deny the shaping, while warm colors and soft modeling in turn disturb the picture plane with the illusions of a third dimension. They might represent nose cones flying dangerously close—and this was 1964 and 1965, with a missile crisis not so far behind. Contemporary eclecticism may never recovery that urgency. Yet it can still hope for a lighter touch.

Don Voisine ran at McKenzie through June 14, 2015, Angelika Schori at Pablo's Birthday through June 28, Pamela Jorden at Klaus von Nichtssagend through June 7, and Lee Lozano at Hauser & Wirth through July 31. Voisine returned through June 29, 2025, when Lena Henke ran at Bortolami annex through June 21.