Associating with Artists

John Haberin New York City

Nina Katchadourian, Mark van Yetter, Dotty Attie

I have seen my share of curating, good and bad, but never curating by free association. Never, that is, until Nina Katchadourian at the Morgan Library.

With "Uncommon Denominator," she plays artist, collector, collaborator, and curator, at once impulsive and with love. Think that is a lot of ground to cover? Downtown, Mark van Yetter runs through one hundred years or more of imagery, in and out of museums. It takes at least twenty works on paper and six times as many images, in what he likens to a novella. Just beware: some good stories do not travel in straight lines—no more than for Dotty Attie, with compelling and colliding feminist art histories.

Katchadourian announces her approach on an opening wall, with the blow-up of a Saul Steinberg cartoon. It shows a museum-goer in her shoes, only male and self-satisfied. J. P. Morgan himself might have found a soul mate. He appears totally absorbed by a Cubist painting—or so it seems until you encounter an oversized thought balloon, taking him from Georges Braque and bric-a-brac through Lenny Bruce and Lenin to whatever else springs to mind, via sound or sense. But then you have to admit: Cubism's very essence was fragmentation, assemblage, and whatever comes next.

The cartoon turns up again later, as itself, among selections from the permanent collection. Katchadourian intermingles them with her own work, in one mad game of (as Monty Python had it) word association football. It does not, though, preclude memories that she cannot let die. Opening wall text gives not just her background, but also that of her parents, Swedish and Armenian. A nurturer barely escaped the Armenian genocide, and that role model's sampler appears, too, as wallpaper facing Steinberg's. Free associations will always end in home—and in what it means to be free.

Curating from childhood

Nina Katchadourian began exploring the Morgan's holdings with Joel Smith, its chief curator of photography, but the collaboration quickly spread to other departments. It could almost be an apology for an old museum's engagement with modern and contemporary. Many objects in the show are themselves collections, like bookbinding tools and, in a photo by Robert Cumming, Faucets I've Lived With. The museum does not name a curator apart from the artist, because who here is not a curator and collector? She herself tends to work in series. And, when she cannot, she can always place a work within one.

Her own photos show books from the museum's collection of American literature—sorted, stacked, and cantilevered like living architecture. Their spines become lines of poetry, like Will You Please Be Quiet next to Look Who's Talking—or Miss Santa Claus next to Chilly Scenes of Winter. These haikus are not without feeling, and neither are her associations. She displays clips from flight magazines, with a pilot as Prince Charming, near a photo of purported UFOs. But then she passes thread through a postcard of New York, leaving traces of flight. And these flights are heading for the Twin Towers.

So many of those feelings relate to childhood and family. Her maternal grandmother kept photographs over the years of her mother as a girl, recording and suspending time. She might be growing without growing up. But then cutouts in the shape of Lake Michigan do the same. Katchadourian remembers, too, her mother's reading to her at night, a terrifying account of survival at sea. She has since collected every edition.

The books display above the model for a yacht and a champagne bottle broken in christening one. It might almost have struck an iceberg. Other associations run through the animal kingdom, including her log of Beatles songs on the radio—because, after all, beetles are in that kingdom, too. (The Beatles, by the time of their breakup, were an endangered species, too.) A skier in free-fall gives way to athletes, dancers, and a photographer herself, Lisette Model, in a portrait photo by David Attie. A seated young woman by Antoine Watteau might seem out of place, but there will always be moments of observation, art, and rest.

Logs and dairies have their place, including the commonplace book of a teenage J. P. Morgan, along with such dignified readings as a Mesopotamian seal from before 3000 B.C., Buddhist texts, and a New England primer. So, too, do maps, as with Lake Michigan. Katchadourian is mapping her world as something personal and obscure. After cut-and-paste world maps comes an actual landscape, or so it seems. The stone monument on the horizon is only the fold in a silver print by Chuck Kelson. Other folds give rise to caution strips from Christine Dalenta—or an abstract composition for Sheila Pinkel.

Has Katchadourian recovered art as the thing itself? Not likely, not when Steinberg returns in portraits by Evelyn Hofer, posing with himself as a child. The free associations keep coming, and it is hard to resist listing them all. They can result in nonsense or a game of trivial pursuit. Still, they might appeal to spectators in pen and ink, by a follower of Hieronymus Bosch at the height of the Renaissance. For a curator, a spectator is a participant as well.

The master key to Modernism

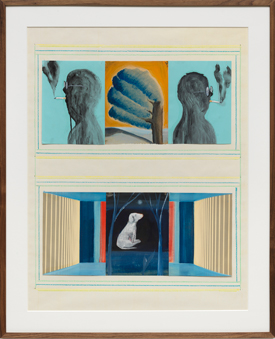

Mark van Yetter offers glimpses of art history, too, with the emphasis on early Modernism. He draws on advertising and commercial art, too, for images you only wish that you could forget. He pictures the life behind it all as well, if only in fragments and, at times, empty rooms. And then he translates all these into his own style at that, between quick but sophisticated sketches and outright cartoons. He calls it "The Politics of Charm," but he is not just turning up the politics or leading you on. It is a lot to handle, for him or for you.

He wants to remain on good terms with the past and present, like Walter Benjamin in the Arcades project before him, and who can say which has greater claim to the shock of the new? That could be the real lesson of the Internet. Try to pin it down at your own risk. Is one image a quote from Edvard Munch? Probably, but the agony is gone, leaving only a naked woman in a shriveled cocoon. Faces have the volumetric simplicity of Paul Cézanne and Cubism, but suspicious stares.

Modern art can get a bad rap, for what white males single out and what they ignore. van Yetter plays fast and loose with its limits. Is that the Joy of Life in blue for Henri Matisse? Maybe, but the frolickers are house pets, and they aspire to feral cats. A curving pathway could belong to a subway platform or a river walk. Either has its dangers.

Modern art can get a bad rap, for what white males single out and what they ignore. van Yetter plays fast and loose with its limits. Is that the Joy of Life in blue for Henri Matisse? Maybe, but the frolickers are house pets, and they aspire to feral cats. A curving pathway could belong to a subway platform or a river walk. Either has its dangers.

If all this seems a little too inviting or way too slippery, so is the Web—and so often as not is art. The gallery looks for insights to the heyday of Postmodernism and "theory," and they, too, could be describing the present. It quotes Jacques Derrida on art as passe-partout, a master key that opens way too many doors. Partout itself means everywhere, and van Yetter has an unusually large Lower East Side gallery. He covers its long walls with a single series. Each work consists of two rows of three images apiece.

They may or may not have much to do with one another, and who is to say? In each row, the outer images come closest to matching, but how? Some present a continuous background, others near clones, and still others mirror images. Tall reeds or patterned walls might be variations on a theme. Rows beneath the rows, of tiny images, run to decorative art. From a distance, you might mistake them for text—captions that the artist refuses to supply.

van Yetter works in mixed media, chiefly oil, although a few additional works on paper amount to paintings—still life, of another early modern motif, pottery. Call them the pass-partout's Part Two. They have warm colors and tactile surfaces, but in slippery architecture. Are those left behind on the floor in the same room or another world? If that were not enough, van Yetter throws in an actual urn, brighter and on a pedestal. It is as close as he will ever get to real life.

A woman's stories

Dotty Attie knows art history cold, so cold that it could bring a chill to the heart of the most detached, unsparing viewer. She also turns it into a woman's stories—of art's past subjects and herself as an artist as well. What would a feminist art history look like? Creative, authoritative artists and historians keep asking, and there can be no one right answer. For Attie herself, a single painting runs on multiple tracks, for the image, the artist, their publics, and their times. Her trick is to let them collide where they may.

Attie works on a large canvas, at least figuratively, but with small parts. Each work amounts to a series of works—or make that several series. A full-scale career survey can have room for only a few. The earliest at her gallery, from 1974, runs to eighty-nine panels, each just three and half inches on a side. It also breaks most obviously with conventional bounds on art, by interspersing images with text from The Story of O. History here is pornography and proud of it.

Does that allow it to express a woman's desire? Maybe, but the male gaze keeps intruding, with quote after quote in grisaille from centuries of male artists. If you recognize more than a handful, more power to you. They look out from portraits and self-portraits, as if shocked to be seen and at what they see. The work itself is What Surprised Them Most, but they could never have seen it.

Starting in 1988, the panels grow, if only to six inches square, and the row gives way to a grid. Like others at the time, she uses the grid as a late modern formal device, but for a postmodern critique. Now the stories plainly diverge, but as stories of a single painting. It might be a girl and a woman by Georges de La Tour in the 1630s and 1640s, Watson and the Shark by John Singleton Copley in 1778, or The Raft of the Medusa by Théodore Géricault in 1819. In each case, texts on gilded panels frame the original, divided and multiplied. They speak of horrors beyond those depicted—and of pressures and punishment directed at the artist. No one, it seems, can escape altogether alive.

In each case, small panels add up fast. Excerpts from a female nude by J. A. D. Ingres (a seated bather from 1808) or Gustave Courbet (crotch forward as The Origin of the World from 1866) look in so many directions that the woman takes priority at last. Attie's usual intrusions from a surprised male can hardly keep up. Finally in 2020 the row returns, this time for what might be stills from film noir—the original, not recreations from Cindy Sherman. I myself can no longer keep up, even with the past. I can only take heart from the title, Be Creative.

Maybe a male should feel lost. I have had my own modest attempts at a woman's art history, but who am I to contribute? Attie did so early on in founding A.I.R., the feminist gallery collective, along with (the gallery notes) Judith Bernstein, Agnes Denes, Harmony Hammond, Howardena Pindell, and Nancy Spero. It is still going strong in Dumbo after more than fifty years, although without so stellar a cast. For all that, she is pretty much new to me. For now, I may not get beyond the surprise, but fine. There are a lot of stories to tell.

Nina Katchadourian ran at The Morgan Library through May 28, 2023, Mark van Yetter at Bridget Donahue through April 8, and Dotty Attie at P.P.O.W. through July 14.