Getting to Today

John Haberin New York City

On Kawara and Storylines

It takes a long time to get to today. On Kawara made it his life work to be sure that you knew it, and he planned his retrospective the same way. He did not live to see his retrospective, but he still shows how to live day to day.

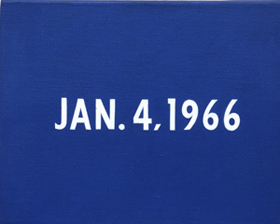

As for getting to today, there is the span of a human life, and Kawara sent nearly a thousand telegrams over some thirty years to remind others of just one thing: I AM STILL ALIVE. There is the course of time and history, and he filled binder after binder from almost the same years, 1970 through 1998, with One Million Years. There is simply Today, as he called forty-eight years of date paintings—almost till his death in July 2014, at age eighty-one. Each bears nothing more than its date of execution, in plain white against a monochrome field, often as not black. And then there is his Guggenheim retrospective opening (be it noted) February 6, 2015, which does indeed take almost its entirety to get to Today. Even then, the museum follows up with "Storylines" in contemporary art.

Alternatives to painting

On Kawara is inconceivable without Today. The date paintings have become a gallery or museum fixture. Their simplicity, in sans serif without spacing, can elicit little more than a shrug. The artist committed himself to completing a painting within the day it began and, if he failed, to throwing it away. If he succeeded, there might always be time for another, looking almost exactly the same. At the Guggenheim, pairs and threesomes hang vertically within the largely single file.

Yet his retrospective also shows how much that account leaves out, starting with its contradictions. Each work belongs to a day, bringing out the process of its creation, while signaling its place in the past. Its predictability accords with an assembly line or, for that matter, the Frank Lloyd Wright ramp, but each has its distinct text and execution. Kawara painted them all by hand with a layered ground, although one would hardly know it, in the native language where he happened to work that day. They aspire to Minimalism and conceptual art, the handmade and the ready-made, the obsessive and the arbitrary, the personal and the universal. He chose as his typeface Helvetica, because it is ubiquitous and because he liked it—or maybe because it improves on Universe.

The account also leaves out half of each work, from the very first date painting on January 4, 1966. Unlike a date painting for Alighiero Boetti, each one comes with a cardboard box intended for a newspaper's page from the same day. Naturally Kawara leaned to the "paper of record," The New York Times, for that, too, is both a personal choice and larger than a human life. It is an alternative means of marking the date as well, just as the telegrams come with all sorts of cryptic codes thanks to the telegraph companies. Last, the account leaves out just how many alternatives he sought. Titled "Silence" followed by a small spiral, like a stylized at sign, this is one noisy retrospective.

Sure enough, it takes till the top floor to get to Today, where one may find relief in silence. Kawara designed the show, with Jeffrey Weiss and Anne Wheeler, to call attention to the alternatives. They may not make him any more lovable or surprising, but they do make him a lot more interesting. I felt that I never really knew him. Along with paintings, clippings, and telegrams, he had any number of other sign systems, like alternative languages of art. And each takes time to get to today.

They include maps, themselves in a variety of systems from street plans to topography. They include picture postcards, again reflecting his location, bearing the time at which he woke. They include lists of the people he met that day, as few as one, and binders of still more newspaper clippings that he happened to read. They include coded messages, incorporating both preexisting texts and preexisting systems, from numeric sequences to Braille. They also include reflections on the body of work itself, with color samples for the paintings and inventories of their making. They, too, define alternatives, such as coded lists and calendars with green dots for days with a painting.

They will have anyone pondering the alternatives, in search of meanings and in search of the artist. Was he, as the museum claims, "devoted to painting" or branding it? (Either stance could appeal to collectors and art advisors.) Surely something was at stake, in thousands of objects so painstakingly assembled. (I did not once spot a typo in his lists of names and spelled-out numbers, from an age before the quick fix of word processors.) But what?

Entering the past

The retrospective offers plenty of clues. Large Plexiglas panes hold the postcards, and binders accompany their contents, further insisting on conceptual art as object. Volunteers read aloud from the million years of dates, both past and future. The clues begin, in fact, in the High Gallery at the base of the ramp, with work from the 1960s. Drawings tossed off in Paris and New York have a slapdash quality, from a monster and abstractions to a keyboard and playing cards, but already they point to both subjectivity and found systems. Before the maps came a painting of the artist's longitude and latitude (somewhere in the Sahara)—and before the date paintings came the year 1965 at the center of a triptych, between ONE THING and VIET-NAM.

Already the show should have one in search of On Kawara. Was he antiwar? That triptych, like Ho Chi Minh, is red. Before paring his message to "I am still alive," his Monologue ran to "I am not going to commit suicide"—and Peter Schjeldahl has compared his doggedness to the futile rolling of a stone uphill in The Myth of Sisyphus by Albert Camus, for whom suicide was the the only question. Was he questioning himself or others, and did even he know? As he put it, "I look for clues to me."

One might look for him again in the postcards of his awakenings. For what it is worth, he favored the Brooklyn Bridge and piers of the city in which he lived for some fifty years, he wrote to a Minimalist in Sol LeWitt and to champions of conceptualism in Lucy Lippard and John Baldessari, and he slept really late. Jet lag might account for part of that, in a serious global traveler from a small town in Japan, but by no means all. One might look for him in a journal entry dedicated to LeWitt "and a pack of Pall Mall." One might even look for him in the date paintings. Actually selections begin well before the top tier for Today, assigned other contexts and tantalizing connections.

Three big paintings suggest awe at the first moon landing. Ninety-seven others, presented as Everyday Meditations, offer a chronicle of exactly three months, beginning January 1, 1970. Not just an aging Pablo Picasso had to date his paintings, and Kawara's thus become a part of their time. The clippings include still more sign systems in TV listings, stock quotes, and advertising along with crises and hard news. Yet it says something about him that he selects pictures of Mick Jagger and Keith Richards, not to mention an obituary for Bertrand Russell, the philosopher. And he keeps returning to issues of race and war.

A seemingly dry, banal artist turns out to have anything but dry, banal tastes. He has a sense of humor, with headlines like "New Haven Same Old Story." Another early version of his telegrams ran "I am going to sleep forget it." Maybe he was not so obsessive after all. The work has come to be about him and about its time just by doing what he intended it to do—to enter the past. He did not think of the typewriter, Western Union, three-ring binders, and eight columns for The Times as vintage media, but now they are.

You may find that it is your past as well. I felt long-forgotten anger at Daniel Patrick Moynihan's call for "benign neglect" of race—and new compassion at a full page for the worn face of LBJ. I had the pleasure of recognition in a gallery's legendary Soho address, on postcards to Paula Cooper. Along with searching for art and the artist, I realized that I was also in search of me. I may not look forward to still more of the date paintings, ever, but they may yet take on the weight of a lifetime. He never got to see his retrospective, because it takes a long time to get to today.

Hungry for Meaning

After Kawara, the Guggenheim is hungry for meaning, but it is finding instead only art. Did he restrict his narratives to dates and the insistent and ominous repetition of four words? Is it enough to say I Am Still Alive? Now nearly fifty artists want more. For Lee Bul with her sculpted unreal cities, art is My Great Account. For R. H. Quaytman, it comes in the "chapters" as inscrutable as a metal hood masking a face. They both contribute to "Storylines."

Agnieszka Kurant has her Phantom Library of books that sound as familiar as The Vidiot but that no one, with luck, will ever read. Trisha Donnelly has her imagined sign language, like a tormented dance, and Catherine Opie her real one, slashed into her skin. Shelves and vitrines are everywhere, even when books are not. Carol Bove has them for shells and peacock feathers, Josephine Meckseper for allusions to Alfred Hitchcock, Rashid Johnson for black soap and houseplants, and Jonas Wood for a collector's library. Pages appear apart from books, too—blotted by Simryn Gill and implicit in Braille incised in copper for Gerard and Kelly or in the typesetter's craft for Ellie Ga. Sharif Waked's Palestinian reads from One Thousand and One Nights, an automatic weapon before him.

Agnieszka Kurant has her Phantom Library of books that sound as familiar as The Vidiot but that no one, with luck, will ever read. Trisha Donnelly has her imagined sign language, like a tormented dance, and Catherine Opie her real one, slashed into her skin. Shelves and vitrines are everywhere, even when books are not. Carol Bove has them for shells and peacock feathers, Josephine Meckseper for allusions to Alfred Hitchcock, Rashid Johnson for black soap and houseplants, and Jonas Wood for a collector's library. Pages appear apart from books, too—blotted by Simryn Gill and implicit in Braille incised in copper for Gerard and Kelly or in the typesetter's craft for Ellie Ga. Sharif Waked's Palestinian reads from One Thousand and One Nights, an automatic weapon before him.

The museum adds stories of its own, starting with wall text. It also asks prominent writers to respond to each artist, their often inscrutable responses accessible with an app. A chart presents a constellation of names and crossing lines, as perplexing as the Asian genealogies of Taryn Simon or the Astroturf Constellation of Gabriel Orozco. Do all these signs and systems confirm or undermine the promise of storylines? For the curators, "storytelling does not necessarily require plots, characters, or settings," but only the "narrative potential" of everyday things. That might include a bare light bulb for Katie Paterson, tube socks as relics for Kevin Beasley, a monument to baked beans and Lucille Ball for Rachel Harrison, or the smashed tea set from a Japanese ritual for Simon Fujiwara.

Of course, the Guggenheim is hungry for something else as well—a presence in contemporary art. The hundred or so works are recent acquisitions, in a museum whose display of the collection usually starts with Post-Impressionism and ends with Wassily Kandinsky. It wants everyone to know that it is still taking on the big issues of its time. Art, it explains, keeps returning to race, gender, and politics. Like MoMA's display of its collecting, as "Scenes for a New Heritage," the show has a decidedly global and politically correct cast. Here, though, critique has given way to something between anxiety and affirmation.

Agathe Snow reduces Easter Island to the scale of children, while Mariana Castillo Deball calls her stellae Lost Magic Kingdom. Iván Navarro fashions neon lights into a shopping cart for the homeless, while Mark Manders pictures girls bisected by plywood and tears. Venetian blinds from Haegue Yang take flight like wings while trapping one in their maze. Pawel Althamer gives a blistering whiteness to his fallen angels, while Pinocchio for Maurizio Cattelan has once again fallen into the lobby pool. Nate Lowman bases his paintings on airline safety instructions, no doubt just in case the art boom comes in for a crash landing. A storyline may even at times run backward, as with the hands of a clock for Julieta Aranda.

Lowman has the style of graphic novels, but humor here is in desperately short supply, and so in the end is meaning. For all its global diversity, "Storylines" is strangely claustrophobic. It has too many fashionable artists, like Ryan McGinley with his photos of street culture, and too many installations. Félix González-Torres curtains the stairs with gold beads, just as his lights fill the stairwell at the new Whitney Museum—as if Frank Lloyd Wright and Renzo Piano stood along a continuum of official museum architecture. For all the old and new media, painting can still tell a story about art and blackness in America. For Glenn Ligon, "They are the ink that gives the white page a meaning."

On Kawara ran at The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum through May 3, 2015, "Storylines" through September 9.