A Bolt from the Blue

John Haberin New York City

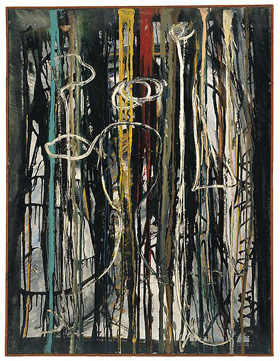

Richard Pousette-Dart in 1951

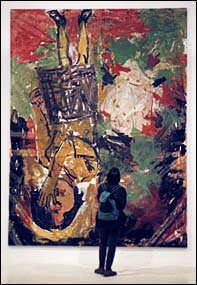

Georg Baselitz: Drawings

Abstract Expressionism was a bolt from the blue. Coming after World War II, as the world itself was remade, it changed the focus of modern art—from Europe to America, from structure to impulse, and from storytelling to abstraction.

So, at any rate, went years of critical advocacy and textbook histories, but what if the bolt took a long time coming to earth? Stranger yet, what if it never quite struck? Richard Pousette-Dart in the 1950s never could give up an obsessive brush and a fascination with the human figure. For him, the bolt had to descend through Surrealism. In work from 1951, he asks what it took for postwar art to change. He later moved to a purer and still denser abstraction, but he had made his mark.

So, at any rate, went years of critical advocacy and textbook histories, but what if the bolt took a long time coming to earth? Stranger yet, what if it never quite struck? Richard Pousette-Dart in the 1950s never could give up an obsessive brush and a fascination with the human figure. For him, the bolt had to descend through Surrealism. In work from 1951, he asks what it took for postwar art to change. He later moved to a purer and still denser abstraction, but he had made his mark.

Could he keep it? In today's art market, it is not easy to lose star status—not even for an artist like Pousette-Dart, who does not always register in histories of postwar American art. This is his fourth high-powered New York exhibition in barely fifteen years and my third review of him as well. Georg Baselitz, too, no longer shocks with his turn to the human figure, but he is not going away. Can his drawings recover the radical departure in his non-abstract expressionism? Maybe not, but they show a gifted, knowledgeable draftsman who took the question seriously.

You can't keep a good man upside-down. When Baselitz inverts his subjects, he does not, the Morgan Library insists, upend anything, least of all art. He seeks only "to emphasize structure and materiality over subject." Still, his turn in the 1970s came as a shock and at times a scandal, with what critics quickly labeled Neo-Expressionism. So which was it, art for the ages or a uniquely German Cold War rebellion? Drawings at the Morgan and the Albertina in Vienna, many a gift of the artist, look back at sixty years of having it both ways.

When lightning struck Surrealism

Abstract Expressionism still rewards a fresh look. Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning have had hefty biographies and retrospectives, and galleries have revisited women and others left behind along the way. The bolt really was a long time in coming. Arshile Gorky had to work his way to the United States, past family loss and the Armenian genocide. Mark Rothko painted New York subways as if the Ashcan School had never left, only darkened, and Adolph Gottlieb painted somber still life as if Paul Cézanne, Henri Matisse, and Cubism had never existed.

Pollock sure had to struggle, demolishing a wall to make room for his first epic mural. Even more, he had to struggle to let go of Surrealism in America, with its tall tales and tall human figures. Pousette-Dart, though, never does let go, even as he was breaking through. He still works on an easel, even as his linen or canvas grows large, with dense rows of slim totems. They face forward, even as their faces remain elusive or blank. And then he packs them further, smaller faces or eyes.

The show's very title, "Spirit and Substance," clings to Surrealism's love of profundity and the unconscious. Pousette-Dart looked within by nature as well. He had no love for the downtown scene, keeping a studio near the 59th Street Bridge like Edward Hopper before him. (Like Hopper, too, he could not stop looking out on the water.) And then he skipped town altogether, to a larger studio north of the city. He created more figures, too, in three dimensions, from red wire. It could not conceivably loop around and through itself any further.

Not that he was looking back or looking away. In work from 1951, he pairs his increasing scale with bright primary colors, so that the muss and fuss build toward a field of raw color. Light descends through and reflects off his figures, as if they were indeed struck by lightning. Brushwork loops all over the place, becoming all-over painting after all. But then his sculpture lives up to another dogma of later Modernism, drawing in space. If his drawing has the misty detail of early Philip Guston, he had his eye on Pollock as well.

His imagery, too, recalls Pollock, the painter of Eyes in the Heat. It may also look further ahead. A 2007 Pousette-Dart retrospective at the Guggenheim and the Drawing Center could have fit right in with the next generation's "pattern and decoration." (I invite you to follow the link to my review then, for a fuller account.) Blank faces also turn to white, like works by Robert Ryman. (His "predominantly white paintings" ran at the Phillips Collection in Washington in 2010—and again, forgive me for starting in on him again now.)

Was he a pioneer or a throwback? As with Alfonso Ossorio, just two years his elder, his obsessive detail stands in the way of the bolder signature elements in most Abstract Expressionism, and he may still be under your radar. In a movement torn between competing critical interpretations, about formalism or expressive gesture, he backs off either one. Still, he casts light on struggles within the movement and what it took to begin. Many prewar abstract artists never did, clinging to hard-edged asymmetry to the bitter end. The bolt still descends from the blue.

Not on solid ground

To be sure, Georg Baselitz had no intention of leaving viewers on solid ground, and the Morgan duly takes note. It calls his work deliberately crude, grotesque, contorted, and provocative—and what better way to establish an artist's credentials than to quote his critics? Those who had given up on realism and then Abstract Expressionism found a discomforting throwback. Those with little taste for macho gestures and Modernism found a mess. "Heroes," a series from the 1960s, includes a man at work on a canvas, a weight lifter, and a rebel, and Baselitz sees little to distinguish the three. The current exhibition's earliest work depicts Pandemonium.

He was on familiar terms with pandemonium at that, enough to abbreviate it to simply P.D. Still, it was John Milton's term for hell, and this is serious business. The very next drawing depicts a cross, and more than one figure with outstretched arms might be crucified upside-down, like Saint Peter. Then, too, these are everyday heroes, his wife included, and he is plainly having fun. In a review of Baselitz in retrospective at the Guggenheim in 1995, I called it the postmodern carnival (and I shall not repeat all that, so by all means follow the link to a fuller picture). A drawing from 1983 has little patience for The Pious Man.

In that drawing, the pious man is green, and a woman in charcoal looking down on him has the last word. Not that the artist's macho reputation is overblown. His everyday world is a man's world, and Neo-Expressionism was a male movement, from Baselitz, A. R. Penck, and friends in Germany to Julian Schnabel in New York. Other reference points are male, too, including Edvard Munch, Emil Nolde, Willem de Kooning, and Robert Rauschenberg, and African masks, although Tracey Emin puts in an appearance as well. He does not make his wife pose nude, but only because he does not need to draw anything from life. Photographs and memories are too strong.

In that drawing, the pious man is green, and a woman in charcoal looking down on him has the last word. Not that the artist's macho reputation is overblown. His everyday world is a man's world, and Neo-Expressionism was a male movement, from Baselitz, A. R. Penck, and friends in Germany to Julian Schnabel in New York. Other reference points are male, too, including Edvard Munch, Emil Nolde, Willem de Kooning, and Robert Rauschenberg, and African masks, although Tracey Emin puts in an appearance as well. He does not make his wife pose nude, but only because he does not need to draw anything from life. Photographs and memories are too strong.

He does have his playful side, and drawing for him was a kind of free play. He neither sketched from life nor, he says, on the way to a painting. Not that one need take him at his word, not when his subjects and style hardly change between media, but his pleasure in drawing for its own sake remains. It gave him the freedom, too, to explore the theme of doubling where his paintings rarely turn away from that sole heroic or unheroic male. A dog casts its shadow, and only the shadow is upside down. Expressionism and its life crises seem far away.

Drawing may even lend credence to that claim for structure, provided it can get along with chaos. Without oil's intense color and impasto, covering every inch of canvas, a little ink has to go a long way. Spare swirls or bare blots spiral outward to become a figure or inward to become a face. Watercolor or gouache adds touches of color, but not at the expense of black and white. His drawings seem lighter in weight than his paintings, in more ways than one, and the show goes quickly. It may also come as a relief.

Baselitz will always have his mixed motives, as the provocateur who wanted to become a star. He left Berlin in the face of Communism and returned to Saxony after the fall of the wall, but his was never political art, and rural Germany, he felt, put him in touch with folk art. His greatest influence, though, was always within. In the last twenty years, the repeated motifs become a weary looking back. The Morgan calls it his "Time Recaptured," after Marcel Proust, but he prefers the modest and melodic "Remix." Aging is like that, modest and weary, even if he has to keep standing on his head.

Richard Pousette-Dart ran at Pace through December 17, 2022, Georg Baselitz at The Morgan Library through February 5, 2023. Related reviews look at Pousette-Dart in retrospective and in white and Baselitz in retrospective.