AbEx Test Patterns

John Haberin New York City

Richard Pousette-Dart

Richard Pousette-Dart will always come with a label, the New York School. Most people know little else about him, and few artists would care to shake off a label like that. Besides, he earned it.

Anyone can explain the label. Pousette-Dart painted to the edge of the canvas, and increasingly he painted large. Call it a stretch, but a Guggenheim retrospective credits him with anticipating the movement's mural scale. He turned early to American themes, from Native American art to the A-Bomb, but never to the urban scene or the pastoral. The Modern snatched up a painting, The Desert, in 1940, when the older artists around him were just beginning to remap modern art with New York at its center.

Most New Yorkers, however, will come to him walking up the ramp to a tower gallery. They will see the largest room first and his later work. They will also see busy, even tacky patterns and thick, reflective surfaces. They may look dazzling at one moment, labored and mannered at the next. Either way, they look like anything but Abstract Expressionism.

Perhaps they will suggest a "minor" Abstract Expressionist, the one that everyone can name but no one can quite remember. They definitely suggest an artist who went his own way. Born in 1916, Pousette-Dart remained a fixture through the alleged death of painting, as artist and teacher, until his death in 1992. A show four years later, focusing on Pousette-Dart's critical years in New York City, helps explain why. Yet the late works also yield some alternative stories about Modernism in America. They give a sense, too, of what happened next.

The pure products of America

Richard Pousette-Dart has all the right credentials. He went on to show at the Willard gallery, which had introduced William Baziotes and Mark Tobey. He exhibited with Betty Parsons, who took on Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, and Clyfford Still, who also taught Deborah Remington. Much of his work in museums still dates from those years. His retrospective originated at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, curated by its director and associate curator. Almost a native New Yorker in the New York School, growing up north of the city, he also came to the movement with a native confidence, as seen several years after his retrospective, in works on paper from the 1930s at the Drawing Center.

Hardly out of his teens, he was still working on the cheap, using stationery from a day job. Appreciating Abstract Expressionism entails knowing how much it had to work its way through, like Surrealism for Pollock, the urban scene for Rothko, or Paul Cézanne for Adolph Gottlieb. Pousette-Dart has often seemed a lesser light because he never did entirely work his way out, attaining a mural scale only by piling on the implicitly male icons. Seen figure by figure on paper, though, his engagement with Oceanic art, Native American art, and its "Water Memories" looks downright liberating. The heroic figures, curated by Brett Littman, also borrow from Western art—not surprisingly, since he studied with Paul Manship, the sculptor of Prometheus in Rockefeller Center. Metal carvings, like pendants or primitive tools, could be his way of prying his way out.

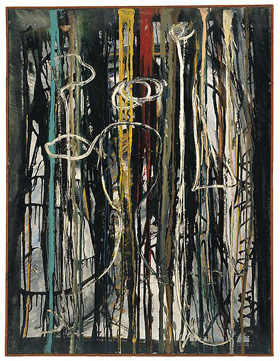

Yet anyone can explain why late work at the Guggenheim does not "look right." For starters, the artist builds up a painting from stiff daubs of oil, many almost the size of a thumbprint and the thickness of fingernail. They run up against one another, overlay one another, and never quite bleed into one another. They cover every inch of canvas, with no breathing space in between, like Joe Zucker without the cotton candy. Pointillism has gone 3D.

Some stick to one color, and a few use all three primaries, but many rely on black, too, and almost all have a serious dose of white. Pousette-Dart often appears to have started with a layer of one color, already too dense to call a ground. With the next, he marks out what will become the thick lines of an image, without really drawing. With the rest, he both intensifies it and comes close to obliterating it. Colors blend, often into still more white, but optically.

One painting represents what he calls fragments of a poem—mostly repeated words on the theme of light and shadow. At least I think they are, since I challenge anyone to read it. The other images are, if anything, all too obvious. One might get the sun, the moon, and plenty of totems, perhaps with rectangular divisions in between. Titles, too, talk of universal truths. The artist distributes some patterns symmetrically or centrally, but for the most part he does not.

Pousette-Dart always has one eye on his craft, the other on eternity. He dwells on the signs and symbols, the mark of the artist's self on the universe and the universe on himself—the very mark that Pollock in time learned to paint out. If one wants to call his generation action painting, the action here moves very, very slowly. If one wants to call it Abstract Expressionism, it is not all that abstract or expressive. The brushwork stabs, clots, and accretes rather than drips, smears, or slashes. If formalism once demanded flatness and purity, the surfaces are anything but flat, and both the images and the technique's echoes of weaving are anything but pure.

Late modern starts

The oddness of those late paintings registers just as much on a gut level. They have nothing of the sweep and sensuality of older abstraction, and they do not seem all that concerned for the nature or future of painting. They lack the playfulness of younger artists just rediscovering painting in the 1970s and after. The images do not mean all that much. I almost dismissed them off the bat as fussy and rigid, and they look that way again in memory. The retrospective undermines canonical terms like major and minor artist, but it does not turn Pousette-Dart into a major one.

In person, however, the optical activity can make anyone dizzy. After a few moments the glow builds, and I had to stay to figure out how it got there. I stayed longer to let it lap over me. When I returned to the bright, flashing lights of "The Shapes of Space," a group show on the ramp, the combination practically drove me right out of the museum.

The technique carries a punch. It also makes an old modernist surprisingly relevant now. The impurity, the garishness, and the totem poles would fit right in with Philip Taaffe year later, and their evolution could track changes in painting for thirty years. The mix of primaries, the swirls closest to abstraction, and the most dizzying works date from the 1960s, the decade of Op Art, Bridget Riley, and psychedelia. The 1970s bring Pattern and Decoration. The 1980s usher in Neo-Geo. Glenn Ligon might have painted those words submerged in black, and everyone today seems to want the gallery to represent an apocalypse.

If these seem like small pleasures compared to the New York School of Jane Freilicher, they do reflect is origins. Pousette-Dart did not so much break with his past, like Philip Guston, as hang in there when greater artists had moved on. His earliest works look like imitations of Picasso by Arshile Gorky, but with faces instead of still life. Their caked whites already set the tone for a long career. Pousette-Dart's first mature images parallel early Pollock, with much the same birds, totems, mysterious writing, and leaden anxiety. Gottlieb, too, first put these hieroglyphics into the boxes of a black grid. They look backward, to Jung's archetypes, and forward to an uncertain future.

If these seem like small pleasures compared to the New York School of Jane Freilicher, they do reflect is origins. Pousette-Dart did not so much break with his past, like Philip Guston, as hang in there when greater artists had moved on. His earliest works look like imitations of Picasso by Arshile Gorky, but with faces instead of still life. Their caked whites already set the tone for a long career. Pousette-Dart's first mature images parallel early Pollock, with much the same birds, totems, mysterious writing, and leaden anxiety. Gottlieb, too, first put these hieroglyphics into the boxes of a black grid. They look backward, to Jung's archetypes, and forward to an uncertain future.

The Guggenheim does a nice job in revealing all this. After so many big empty shows, it returns to modern art in a refreshingly small way. For barely a month, it takes a lesser-known but representative painter, makes no preposterous claims for him, uses the different scales of two adjacent rooms well, and concentrates on just forty paintings and a few drawings. Why should retrospectives have to loom so much larger? The curators also cheat in the interest of the story. Only the drawings and one or two paintings show Pousette-Dart's looser crossed lines or curves rather than all this precision, and one would never know that he really did lean heavily on symmetry for the rest of his life.

Mostly, however, the continuity of his art obliges one to recognize other currents in Modernism, not just the autonomy of fine art. Like the Abstract Expressionists, he merged Cubism and Surrealism in order to break with either one. For them, too, the mix let painting stop telling obvious stories—to become abstract, if you will—without losing concern for the shifting identities of figure and ground. And for them, too, the inch or so of space in front of the canvas became simultaneously a new fiction and an extension of the room. It also became a battleground for art ever since. Maybe Modernism never did achieve purity and never did stray that far from the poles of pattern painting and Freud for beginners.

Drawing in wire

For all that, a focus on his critical years shows why Pousette-Dart still hangs over so many artists. In 1950, he strung a network of wire across a makeshift frame. It has no pretense of permanence or perfection. Little is welded, much less carved. The frame consists of four slats of the same copper color, and the wire loops about it simply to stay put. The weave spreads loosely but thoroughly, like an "all-over" painting," gathering to accentuate a few central horizontals and verticals, before finding thicker nodes almost like drips. The composition looks improvised but geometric, starting with the square frame.

He could pass for yet another contemporary European, keeping up the veneer of gesture and abstraction for a grungier age. The poshest block in Chelsea has more than enough of just that, as with the slashed canvas of Lucio Fontana and Sterling Ruby's ceramic vomitorium a month before. But no, this is the real thing, from the very year of Pollock's One. Someone other than David Smith pulled off Abstract Expressionist sculpture after all. Talk of "drawing in space," but the work truly does hang by wires, like a painting.

Pousette-Dart knew Pollock quite well, thank you. Again, the same dealers championed them both—and if the sculpture comes as a surprise, New York has not seen it since it showed at Betty Parsons. Could Pousette-Dart even have pride of place? Although the youngest in a movement that matured slowly, he entered a New York museum quickly. "East River Studio" is "Abstract Expressionist New York" when that meant not East Village art but an abandoned brewery in midtown. The artist caught the morning light there until the end of an era—when he moved upstate until his death in 1992, much as Pollock, Lee Krasner, and Willem de Kooning headed for eastern Long Island.

Indeed, he knew them all too well. de Kooning's black and white hang over the younger artist's purest abstraction. Pollock's "personages" hang over still more of the show, long after Pollock outgrew them. So does a determination to trace and layer those signs, symbols, and impulses. They help explain Pousette-Dart's fussy, conservative reputation. Did I say that he always had one eye on his craft, the other on eternity? Yes, but he also had one eye on the river.

When an artist is a textbook figure, like Smith or Picasso, shows keep adding one footnote after another. When one is not, glimpses come slowly, as in 2007 at the Guggenheim, which made a case for later work—or the Phillips Collection last year, with "Predominantly White Paintings." (Not coincidentally, it was also showing Mr. White himself, Robert Ryman.) This time, one may have the most telling glimpse of all. It comes across as a survey all by itself, without leaving his New York years. Morning light creates those cloud-like whites, while the personages have sharp contrasts of black and color. Relaxed and animated as conversation, they offer an alternative American Surrealism.

What the sculpture lacks as sculpture, it makes up in illuminating the painting. It also forges a connection to the future. One could mistake some freestanding "birds" for sculpture by Richard Stankiewicz, six years younger. Loops of yellow on canvas detach themselves from the ground, much like spheres or knots by Terry Winters. If only the crusty wire had more of Stankiewicz's weight and found objects, and if only the loops were not fallen angels. Pousette-Dart still looks precious after his generation's iconic energy and iconic form, but if one wants a great retrospective, it may as well end in 1956.

Richard Pousette-Dart ran at The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum through September 25, 2007. "East River Studio" ran at Luhring Augustine through December 17, 2011, and early works on paper at the Drawing Center through December 20, 2015. Related reviews look at Pousette-Dart in white and in 1951.