The Suspicious and the Dreamers

John Haberin New York City

Everything Is Connected: Art and Conspiracy

Adelita Husni-Bey, Mariana Castillo Deball, and Mika Rottenberg

There are two kinds of people, those who get it and those who do not. And there are those who get it because they know that everything is a lie—and those who get it because everything you heard is true. Oh, and those like me heading as fast as possible for the exit.

You know who you are. You may have pored over the historical and public record, to penetrate the "controlled media," "bureaucratic complexity," and their pervasive, stifling "deceit" or worse. Or you may have lost it entirely—"down the rabbit hole" into a world of "fever dreams" that may or may not look much like art.

Will anyone know the difference, and will anyone care? Is this the silly season or what? Nope, it is just another busy fall in the museums and "Everything Is Connected: Art and Conspiracy" at the Met Breuer. And if that sounds like a muddled idea of political art, wait till lawyers and new media enter the picture, with Adelita Husni-Bey, Mariana Castillo Deball, and at the New Museum. Or wait till you tunnel through the earth in search of connections, with Mika Rottenberg. You will discover who you are.

You know who you are

It may sound halfway amusing that a show in which "Everything Is Connected" divides neatly into two parts, for the suspicious and the dreamers, but then irony here is in short supply. It may also sound disturbing that its paranoia echoes many emerging artists, those who consider the system rigged, but then they are in short supply here, too. It may sound even more disturbing that the supposed realists resemble wingnuts decrying the "deep state," but then it is hard here to tell the two sides apart at that. Peter Saul turns up among both with paintings of Hitler's brain and California under Ronald Reagan. Much else, too, might count as "sinister pop," like a graveyard gas station by Tony Oursler on the fantasy side and a map of world suffering by Oyvind Fahlström among the serious. Much on both sides might count as agitprop as well, like Sarah Anne Johnson in search of CIA experiments on grandmothers—or Peter Nagy in connecting "self-actualization" to Pepperidge Farm and the Museum of Modern Art.

Political art always runs the risk of losing it. One side of the show revels in fantasy, like Jim Shaw restaging small-town America amid the creature comforts of LA. The other buckles down all the more firmly, like Emory Douglas in defense of the Black Panthers—just as in "Soul of a Nation" at the Brooklyn Museum. And sure, they are every bit entitled to their anger or their fun. The latter helps power the revival of painting with Sue Williams, for whom All Roads Lead to Langley (the site of the CIA headquarters). The anger may not have sped medical research into the AIDS crisis all that much after all, but it left indelible memories of Gregg Bordowitz and Silence = Death.

The dour side can call up the driest and shrillest of the 1970s, like Hans Haacke mapping Manhattan real estate which earned him the wrath of the Guggenheim. (Somehow neither Leon Golub nor Sue Coe makes the cut, but they could have.) The silly side, in turn, can excuse bad boys like Shaw and Mike Kelley. Still, both sides were ahead of their time. Donald J. Trump and MoMA still profit from cheesy high rises, while Fahlström took up the refugee crisis some forty-five years ago. When Kelley singles out the influence of the Democratic Leadership Council, I can hear those certain that Hillary Clinton stole the nomination.

I may not agree, but the greater problem lies elsewhere—in how little the art has to say beyond cartoons and temper tantrums. Sarah Charlesworth agonizes over newspaper coverage of the Red Brigade in Italy, while Trevor Paglen photographs "black sites" of torture in Kabul from the outside. Yet they look thoroughly unrevealing compared to real investigative journalism. The public record has its limits. They also seem mired in a time before the Web, just when the surveillance state has taken on a greater currency. Jenny Holzer does way better when it comes to Holzer's crawl screens, by sticking to the medium and the message.

The curators, Doug Eklund with Meredith Brow and Beth Saunders, specialize in photography, meaning the serious stuff, but plainly the rabbit hole is having a much better time. Yet fantasy has its limits, too. Raymond Pettibon, Wayne Gonzales, and Rachel Harrison all take up the Kennedy assassination. Pettibon's doodles and a peach portrait by Gonzales mean little, though, while Harrison's attempt to bring Dealey Plaza into the museum with trash bags and Sheetrock pales beside her visionary photographs and monumental portraits. Do these artists even believe in conspiracy theories, any more than Cady Noland believes that Bill Clinton killed Vince Foster, or are they satirizing them? It might help if they, too, had more to say.

Entering via the reality-based community makes the show's first conspiracy theories about art. Mark Lombardi, for once, traces money laundering in the Middle East rather than the art world. His diagrams resemble Alexander Calder mobiles all the same, only in 2D. Alas, Alessandro Balteo-Yazbeck, who suggests a connection, is more concerned with how New York stole the idea of the avant-garde—the claim of a 1983 book by Serge Guilbaut. Do I really have to revisit that again? I might if art could deliver at once on the irony, the reality, and the fantasy.

Living theater

Quick: what do you get when you cross a pack of lawyers with avant-garde theater? A dark room, an indecipherable story line, and a lot of talk. Adelita Husni-Bey has them all with Chiron, but also something more. She asked lawyers for families facing deportation in New York to star in a video, modeled on the Theater of the Oppressed in Brazil forty years earlier. Their harrowing accounts can grow oppressive, too, but not without hope. They also immerse the viewer in a living theater.

A guard warns visitors to take it slow, with good reason. Artists before have had one stumbling dangerously in the dark, like Anthony McCall and Bill Jenkins, and between the First and Third Worlds, like Tania Bruguera. Here videos are in progress, one on a raised platform in the dark. Sheer curtains surround then to all sides, covered with words. One can hear the voices of children and then a single insistent one. All invite one to join them on stage.

First, though, one has to find one's way. The stage turns out to have broad central stairs leading up—and a wheelchair-accessible ramp by the room's entrance. The curtains line an ample corridor on all four sides, where one can stop to read or to listen. It feels like a labyrinth all the same, much like the legal system for undocumented immigrants. Augusto Boal based his theater on Paulo Freire's Pedagogy of the Oppressed. It also arose around the same time as the touchy-feely performance space of Elizabeth LeCompte's Wooster Group and Judith Malina's Living Theater here in New York.

Theater of the Oppressed may echo the Theater of the Absurd—but who has time any more to relish the absurd in the face of torture and exile? Irony aside, the lawyers in UnLocal provide pro-bono representation, Husni-Bey has no doubt of their righteousness, and neither, no doubt, do they. The narration traces the present crisis back to colonialism, just in case that was not obvious. Still, the children alone offer hope. The artist, based in Italy, has them imagining a new life on the moon or a desert island. That may not sound promising, unless you remember Lord of the Flies as a comedy, but the visitor can still take center stage, even in the dark.

In Greek myth, Chiron was a centaur skilled in medicine, and Husni-Bey takes him as an emblem of the wounded healer. Mariana Castillo Deball has her myths and prospects for healing, too. Her Third World has survived imperialism as well as more ancient oppression, and it is moving along just fine toward another dimension. It does so mathematically, should you trust her, as she transforms found images into resin blobs. It does so imaginatively, as she pierces her own suggestive patterns right through old books—themselves past explorations of her native Mexico. As their Latin title puts it, I Give So That You Will Live.

Castillo Deball is always a giver, but then the Lord giveth and the Lord taketh away. A large sculpture topples and preserves in glass a Mesoamerican deity of earth and death, a potent combination. It may not look recognizable, but then, as its title has it, No Solid Form Can Contain You. The artist or a goddess has also covered the floor with plywood, inlaid with an antique colonial map of a town in Oaxaca. If galleries normally use floors like these for self-protection in the face of art, visitors may enjoy the work's safety, even if it does not quite add up. One can explore the room, the region, and the perceptual space of others.

Pointing a finger

Mika Rottenberg is pointing a finger at you. It protrudes from an otherwise bare wall, with a long, bent, blue, and tortuous nail. Every so often, it twists in stern but silent reproach. In the same near empty room, an orange ponytail flips momentarily upward, while red lips interrupt the view between them for a puff of smoke, without a cigarette in sight. Two frying pans on hot plates let off steam, too, much like the artist. She is teasing you, flirting with you, putting you off, and putting you down.

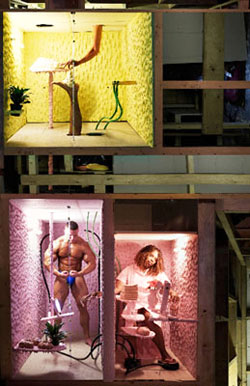

Rottenberg has been pointing fingers for some time now, more often into painfully confined spaces. They point for her to bodily pleasures, shame, and discomfort, but also to exploitation in the Third World. In NoNoseKnows, her 2015 video, Asian women toil endlessly over cultured pearls, while an overweight "fetish worker" rides her motorized wheelchair past depressing housing and trash piles. She passes through closed doors and empty corridors, only to end up where she began. There she attends to floral arrangements, ignoring the plastic bags and buckets of pearls at her feet—and in the room with you. She has less success ignoring the plates of noodles piling up before her.

For Rottenberg, pearls and pasta have one promise in common, consumption—and a global culture and economy of consumption is consuming women. It is none too pretty. She has tracked women farmers molding cheese,  sumo wrestlers as the brute surface of their skin and hair, lettuce and rubber harvesting, bodybuilders and fashionistas. The abasement of human flesh recalls late Cindy Sherman, but without the comforting lens of art film and popular culture. The disturbing performance acts and entertainment value recall Carolee Schneemann and Pipilotti Rist, but without the promise of liberation. Even if the actors could break free, cheap plastic would and contaminated oyster beds would still be putting the world to waste.

sumo wrestlers as the brute surface of their skin and hair, lettuce and rubber harvesting, bodybuilders and fashionistas. The abasement of human flesh recalls late Cindy Sherman, but without the comforting lens of art film and popular culture. The disturbing performance acts and entertainment value recall Carolee Schneemann and Pipilotti Rist, but without the promise of liberation. Even if the actors could break free, cheap plastic would and contaminated oyster beds would still be putting the world to waste.

Rather than offer a career survey, the New Museum picks her up with the pearls and carries her into the present. Born in Argentina, Rottenberg is still tunneling between the First and Third Worlds. Another video follows train tracks into underground caverns, emerging in a wholesale market in China and a Chinese restaurant in Mexicali, on the Texas border. That may sound like a flash point for haters of refugees and immigration. Yet globalization is itself confining, even as it carries her across the world. Her latest video, Spaghetti/Blockchain, even sounds like a planet's worth of food trends and technology.

This one opens past ceiling fans and colored lights. They get one's mind spinning, even before the hall of mirrors of a particle accelerator in Switzerland, "throat singers" in Siberia, and a potato farm in Maine. One or the other provides the material for a countertop, where eggs sizzle and something under the knife wiggles. Rottenberg also has matter and antimatter in mind when she calls the show "Easy Pieces." NoNoseKnows ran at the Met Breuer with Five Easy Pieces by Steve McQueen, and she has the same "in your face" attitude as Jack Nicholson in the movie of that name. She took her title, though, from popular lectures on physics by Richard Feynman.

Regardless, nothing here seems easy. Men rarely appear—and never unquestionably male. One in a suit and tie wiggles his painted toes and sneezes uncontrollably as his nose grows like the pointed finger, spewing rabbits and raw meat. (Is it a coincidence that the "fetish worker" is named Bunny?) Rottenberg may not need a retrospective, when every work offers a career summary in its excess and obsessions. By the elevators, an air conditioner drips onto a houseplant, keeping it alive at the cost of one last protracted water torture for the artist and viewer.

"Everything Is Connected" ran at the Met Breuer through January 6, 2019. Adelita Husni-Bey and Mariana Castillo Deball ran at the New Museum through April 14, Mika Rottenberg through September 15.