2.28.25 — Is Paris Burning?

Art was in turmoil, so why not the Eiffel Tower? In the cool hands of Robert Delaunay, it barely touches the earth with its unforgettable steel frame.

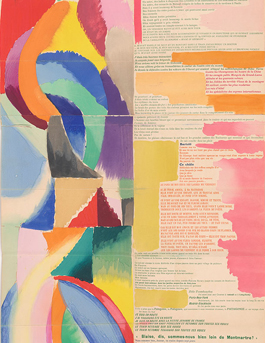

Is it rising into the sky or collapsing once and for all? When he paints it again in bright red, has it caught fire, figuratively or for real? How about all at once? So it is with “Harmony and Dissonance: Orphism in Paris,” at the Guggenheim through March 9—and I work this together with an earlier report on Sonia Delaunay as a longer review and my latest upload.

Is it rising into the sky or collapsing once and for all? When he paints it again in bright red, has it caught fire, figuratively or for real? How about all at once? So it is with “Harmony and Dissonance: Orphism in Paris,” at the Guggenheim through March 9—and I work this together with an earlier report on Sonia Delaunay as a longer review and my latest upload.

It was 1911, and Cubism had shattered convention with its assault on structure and representation. Pablo Picasso had not yet introduced rope into his illusory tabletops, marking the transition from Analytic to Synthetic Cubism. Already, though, one could speak of a choice at the very heart of modern art, between Cubism’s line and, thanks to Henri Matisse, Fauvism’s color. But why choose? Robert and Sonia Delaunay wanted both line and color, and they were not alone. The tall gallery off the atrium has a startling display, from their rainbow colors to the deep blues of František Kupka and Francis Picabia.

It was color in motion at that, like Kupka’s closely packed curves of translucent whites, akin to stop-action photography years later. Marcel Duchamp dismembered a nude in much the same way, shocking New York at the 1913 Armory Show. Many an artist now at the Guggenheim exhibited there as well, including Albert Gleizes, more often remembered as a minor Cubist. Gleizes returned to New York during World War I after serving in the military. For Europe, the sense of turmoil was all too real. And still modern art’s School of Paris soldiered on.

But was it Orphism? Guillaume Apollinaire, the poet, coined the term, but history books have mostly settled on Delaunay’s choice of Simultanism. The curators, Tracey Bashkoff and Vivien Greene, want something more poetic and encompassing than he could ever have produced. They include many outside Simultanism, like Gleizes and Duchamp. They see an international movement as well, from Natalia Goncharova in Russia to Morgan Russell and Stanton Macdonald-Wright in America—perhaps the first in modern art. Gleizes himself painted the Brooklyn Bridge with the same broken diagonals as Delaunay’s tower. The turmoil had spread.

The shows sees the same exploration of motion in the tumbling bodies of Fernand Léger in Paris and Gino Severini in Italy—and the same approach to abstraction. In fact, Orphism got there first, before Vasily Kandinsky. It sees the same exploration of color in Paul Signac. Was Post-Impressionism more “scientific” than Orphism could ever be? Perhaps, but Signac had also painted a critic and dealer as a magician, pulling a flower out of his hat. This was turmoil, but it was still magic.

What, then, sets Orphism apart if everyone belongs? It was not just color or line in motion, but also a device to achieve it, circles. Sonia Delaunay has dozens of them, and Robert Delaunay changed the shape of his paintings to disks. They delighted in the globes of Paris street lights and in a Ferris wheel, only a stone’s throw from the Eiffel Tower. For Marc Chagall, the Great Wheel gathers light within its circle like a nighttime sun. The parallel to color wheels in color theory (Kupka’s Disks of Newton) must have been hard to miss.

Modernism has another pair of stories to tell besides line and color. For critics like Clement Greenberg, it meant an escape from clichés and conventions into a higher realm of art. For Postmodernism, it has meant instead putting a torch to fine art as distinct from life. It had to pass from Cubism to Dada—or, with Sonia Delaunay, from painting to fashion as a part of life. And here, too, Orphism refuses to choose. Art and its fire were in the air, like the Eiffel Tower and the Brooklyn Bridge.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.