Longing for History

John Haberin New York City

Garrett Bradley and an African American Field Day

Jamaal Peterman and This Longing Vessel

More than a hundred years ago, a full-length film celebrated African American culture and its own black cast. Abandoned in post-production, it languished all but forgotten, but it survived—not intact, but still it survived.

Now restored, it has a story to tell about just what it means to speak of African American culture or survival, and it may not be the story that Donald Trump's America wants to hear. If that sounds like a metaphor for a larger history, it is also raw material and an inspiration for Garrett Bradley at MoMA. She integrates footage from Lime Kiln Club Field Day into her own, as America. It draws on painful memories, but it is a celebration all the same.  If African Americans for Bradley are proud survivors, so they are for Jamaal Peterman in a starker but also more colorful present. As for the Studio Museum's artists in residence as guests at MoMA PS1, "This Longing Vessel" treats them like stars that are only beginning to fade.

If African Americans for Bradley are proud survivors, so they are for Jamaal Peterman in a starker but also more colorful present. As for the Studio Museum's artists in residence as guests at MoMA PS1, "This Longing Vessel" treats them like stars that are only beginning to fade.

Having a field day

With her title, as with her work, Garrett Bradley may have you thinking of Jacob Lawrence and his American Struggle at the Met—and everything about the 1913 silent film on which she draws a struggle. Shot when "full length" meant about an hour of footage, it lay in pieces in the Biograph vaults. If the silent era takes on an eerie resonance in the face of the silencing of African Americans, the film also lost its titles. MoMA, which completed the restoration in 2015, relied on a lip reader to recover fully its dialogue and even its plot. Its star, Bert Williams, vies with two other men for the hand of a black woman. It climaxes in a kiss, which must have been shocking enough to its white producers, and continues on to a protracted celebration.

In all fairness, less than a third of the period's movies survived, and this one has found a new beginning. Bradley is happy to contribute twelve scenes that evoke both history and everyday life. One can single out the old footage only by its jerky motion, if at all. Her America shows star athletes, a band leader, a bonfire, and faces behind a chain-link fence, but also a sleeping child beside a vintage radio and a well-dressed gathering raising its glasses in a toast. What are they toasting? Who knows, but then who here needs an occasion to celebrate?

Not that the living is easy, not in this America, where achievement is tangled up with violence and exclusion. A baseball player alludes to the birth of the Negro Leagues apart from the majors, and an actual band leader back then was shot and killed. The athletes also include runners, in close-up, and one can feel their speed but also their overwhelming strain. Not so long ago, Arthur Jafa isolated another racer in the video collage of Love Is the Message the Message Is Death, along with another fatal shooting. That runner for Arthur Jafa seems beyond strain, but he may still collapse after breaking the tape.

Not that Bradley's curator, Thelma Golden of the Studio Museum in Harlem, has anything to hide, but the old film has its complications, too. You can catch more of it in the second room set aside for the permanent collection in MoMA's 2019 expansion, still on view after its 2020 "fall reveal" and 2021 reveal. Williams, a vaudeville entertainer as well as writer and director, turns out to have performed in blackface. The extended celebration has its marching band, but also (ouch) a watermelon-eating contest and a cakewalk. As another black artist, Kara Walker, found out the hard way, noxious stereotypes can earn serious protests, even when they ring out in protest themselves. Should it matter that an interracial production long ago was having a field day?

Only in art can triumph evoke such tears and fears. For Bradley, a full twenty-three minutes of strain only heighten the triumph. For Jafa, the very lack of strain leads to tragedy. That to my mind makes his video more wrenching and unforgettable. Still, they belong to the same struggle. Rather than let one diminish the other, one might do better to ask why the difference.

Part is Bradley's dedication to reconstruct the past (and remember what Reconstruction meant to American history). Part, too, is her video as installation. Screens set at right angles, suspended from above, cross the gallery like an enormous X. Images just out of synch prolong a wary but joyful moment in time. The projection also splashes off the four channels and onto the walls, as both transience and light. Within a scene, a bright object piercing the darkness can blur even as it gathers light—but then so can lived experience.

Not just behind bars

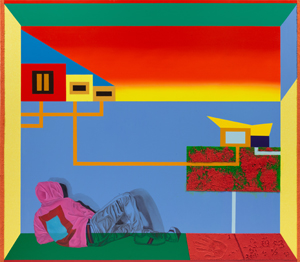

Jamaal Peterman sets his figures in a stark but colorful landscape. Everything about the scene is bold, confident, and reassuring—except for them and where they find themselves. The African American artist uses bright, unnatural hues for scenes without a hint of nature. Skies may run to solid yellow and orange fields, with deep blue threatening at any moment to emerge from between and behind. A paler sky blue is more likely to describe the earth. A modulated red, reminiscent of sunsets, sticks even closer to the ground.

It necessarily covers the ground, for sunset is already closing in. It seems to have brought his protagonists to earth as well. Most often one to a painting, they lie neither prostrate nor at rest, but on their butts or on their knees, alive and reeling. Peterman renders them in modulated blacks akin to fine pencil or charcoal drawings. It brings them alive, but make no question: in their shadows and their colors, they just plain do not fit in.

It necessarily covers the ground, for sunset is already closing in. It seems to have brought his protagonists to earth as well. Most often one to a painting, they lie neither prostrate nor at rest, but on their butts or on their knees, alive and reeling. Peterman renders them in modulated blacks akin to fine pencil or charcoal drawings. It brings them alive, but make no question: in their shadows and their colors, they just plain do not fit in.

He also rubs their faces in their ground. Red sand heightens the paint's vivid color, near the center of a composition in an unsettling space between the sky and the ground. It heightens the boldness, but again at the expense of the barest touch with nature. The dubious hero leaves his hand print in one textured field where he might have fallen and a few numerals to its side, none of them complete or clear. He might have failed at defacing them, like Siobhan Liddell, or they might count off his fate. The texture, so rewarding on the surface, is likely to get under your skin as well. The fate of a young black male here could well be yours.

The landscape may not be natural, but it is less than urban, too. Just for starters, the fallen men have no one to ask for help, in a setting without need for museum social distancing. The colorful plain geometry that seems so confident at first bears down as well. It resolves itself into the blank walls and towers of, I can only assume, a prison. Two walls do more or less achieve graffiti, with child-like pastel scrawls to one side, but silhouettes of dead leaves or erect bodies to the other. Color along a painting's border resembles a beveled frame, projecting the scene into depth while confining it once and for all.

A second person does enter one work in confrontation, but faceless and in confrontation. He encounters the other not in the hopes of terror of a prison uprising, but in the brutality of armed suppression. As one title has it, You Know It's Coming, and others are no more encouraging. Rise and Shine suggests the broken sleep of a harsh morning call. Broken Democracy could stand for the whole show or the whole of society, while the armed confrontation is Robin Hood. So much for folk heroes and fairy tales.

Peterman's confidence is contagious all the same. It just does not happen to lie in the cheery truisms of black pride and racial identity. The show of self-taught and therapeutic prison art at MoMA PS1, "Marking Time," has it at once too easy and too difficult. Resistance for Peterman is a matter of course, but not of release. It lies instead in his confidence as a painter within the big, bright idioms of sci-fi and late Modernism alike. There is no longer much time or room to play, and it will just have to be in the sand.

Emerging divas

The artists in "This Longing Vessel" may be just emerging, but they are already divas. They may be artists in residence from the Studio Museum in Harlem, but they are not merely longing for the big time. They are, they want you to know, breaking out. E. Jane Maxine sets the tone by the entrance at MoMA PS1, with a photo in black and white. She poses life size as Diana Ross or Whitney Houston, and she looks larger than life. She has a gala opening crowd applauding on video, too, and they could be looking up to Elliot Reed and Naudline Pierre as well.

Not that the Studio Museum has failed to launch its share of stars, including Tschabalala Self in 2019, and not that this year's crop is on view in Harlem. That museum has closed for expansion, but they have simply gone on tour, and the arrangement works out well for all venues. The pandemic has taken its toll on the former alternative arts space in Long Island City—which otherwise lies empty apart from the display of prison art. (Cross your fingers that its contributors may all one day emerge from mass incarceration.) Thelma Golden, the Studio Museum's formidable director, has a temporary home as well, as guest curator at MoMA. There she brings Bradley, whose video takes a more sweeping and probing look at African American culture past and present, high and low.

Despite its three rooms to Bradley's one, "This Longing Vessel" (an allusion to Toni Braxton) looks modest by comparison. When the museum in Harlem reopens, the annual event will no doubt have outgrown its mezzanine, where artists spill over into one another. MoMA PS1 confines each to a room, with other rooms in the wing boarded up. It is not, though, for lack of ambition. The grain of Maxine's pose and her face shielded from the camera already mark her as a legend. Her last name in neon marks her as the kind of star that fans put on a first-name basis.

In reality, she has created a different alter ego, not Maxine but MHYSA—its basis in Game of Thrones as inexplicable, I suppose, as stardom. As for the video, it unfolds on a TV worthy of PBS, in a concert hall but also in nature, which all but sings along. Behind a partition, she lets her hair down, up to a point. She performs in her studio clothes to an audience of one, not counting you and her reflection in a wall-size mirror. In Lieu of an Explanation or an Appeal, a confident title runs, They Shouted and Stomped and Screamed How Else Could They Express Their Longing to Be Free. You may ask yourself whether an African American can ever really break out.

Reed has in fact broken a hole in the wall at floor level, but nothing lies behind it apart from its own debris. His subject is lost lives, in a year of Black Lives Matter, but also his own command, which extends to a microcosm of Western culture. The members of a string quartet, all of them white, perform on separate monitors while he directs the scene from an identical screen at dead center. His narration is not much easier to follow than MHYSA, but it involves two deaths from drugs. Empty black sweats lie on the floor—on salt crystals, I imagine, as a substitute for crystal meth. A text painting of BLOOD hopes for a finer blood in blue on blue, but a second across from it, for NUDITY, supplies the red.

Longing for a still finer heritage? Pierre will settle for no less than "divine ancient or other spiritual and ancient hierarchies." Her solo figures recall Symbolism and Art Nouveau, on slim panels tapered at each end. Multiple figures occupy a dark but idyllic nature recalling Paul Gauguin. For all three artists, escapism may well derive from an urgent need for escape. Wish all you want for a less pretentious title and a greater grounding on planet earth, but hope, too, for the rest of the museum and for art after Covid-19.

Garrett Bradley ran at the Museum of Modern Art through March 21, 2021, Jamaal Peterman at James Fuentes through January 17, and "This Longing Vessel" at MoMA PS1 through March 14.