You Are Not Alone

John Haberin New York City

Lucy Raven and Karyn Olivier

Amanda Williams and Museums Return

You are not alone. It may have felt otherwise during the pandemic, for months at a time—most especially while museums closed. I know it did for me.

Lucy Raven, though, shines a light into every corner of Dia:Chelsea, and who knows what she may find? I had just begun to savor its changes when it landed in a corner, only to pick out someone else. I nearly jumped out of my skin. Of course, I still kept my social distance, and so did she. Amanda Williams at MoMA makes that easier, too, with a museum's worth of chairs but little seating, while Karyn Olivier remakes gallery architecture out of its seeming collapse.  Do they show the way to art after Covid-19 or call it further into question?

Do they show the way to art after Covid-19 or call it further into question?

Dia's concrete foundation

I could almost have left for somewhere remote and alone, perhaps Dia:Beacon upstate. Dia started out in the 1970s with ever so classy spaces, as Heiner Friedrich shut his Soho gallery and, with Dominique de Menil and Helen Winkler, devoted himself to long-term installations by such Minimalists as Walter de Maria. Not even de Maria's New York Earth Room, an actual room full of dirt, could not disguise the pristine whiteness. Dia's first Chelsea location has since served such class acts as the Independent art fair and Hauser & Wirth gallery, while Dia itself all but abandoned the city. Now ARO, or Architecture Research Office, has combined three factory spaces just across the street into something more raw and spacious. Lucy Raven can only begin to shine a light or, on video, to bury it in concrete.

You may associate the Dia Foundation with such macho figures as John Chamberlain and Richard Serra—even if men in Minimalism like Robert Ryman are something else again. And Jessica Morgan, the director since 2015, brings a commitment to such women as Dorothea Rockburne and to Sam Gilliam, the African American painter of soft, stained, unstretched canvas. But then I have long had a mammoth spider by Louise Bourgeois in Dia:Beacon as my screensaver. And Minimalism, as for Carl Andre and Robert Irwin, was always about the space around and within the weightiest of objects. Raven illuminates exactly that space. She also brings to bear some traditionally male associations.

Dia:Chelsea has two of her Casters, a pun on swiveling and casting light. For each, she mounts a projector high on the wall. As its armature twists and bends, a circle of light elongates into an oval on the floor or splashes onto the wall. Sure enough, it caught another visitor there with me as if she had been lying in wait—or a target all along. Does the armature suggest a loaded weapon? Weapons manufacturers first developed it, and a slim gray line crosses the circle of light as in a gun sight.

Does the device also recall a film projector or mobile camera? The armature has adapted to all sorts of purposes, those included. I thought of Alfred Hitchcock and his crane shots, which similarly miss nothing. And the west gallery has a third work, Ready Mix, on the curved screen of a movie house. Its forty-five minutes follow the manufacture of something as hard and insensitive as concrete, because Raven refuses to turn away. I joined others on tiered seating (ample enough for social distancing) and settled in for the course.

A steam shovel enters an enclosure to load up on gravel that then runs the course of a conveyer belt. It can, though, seem instead to pick up where the first room left off. I entered to see only an extended churning of the light. By the end, I had seen a circular opening onto darkness and a rough curtain descending over an entire screen of light. If the lone woman had not been shocking enough pinned against a corner, the transformation of seeming abstraction into documentary realism is brutal, too. But then de Menil did inherit an industrial fortune.

It takes time to mix concrete, and it can disrupt a sense of time as well. Who is to say which to believe—the realism, the curtained wall, or the puddle of light? This being Minimalism, albeit from an artist not yet born in the early 1970s, the gallery may have the last word after all. On my way out, its beams and exposed brick looked better than ever, along with the splashes of light. Welcome Dia back to New York City and New York back to human company. In concrete or light, nothing is set in stone.

The color of disaster

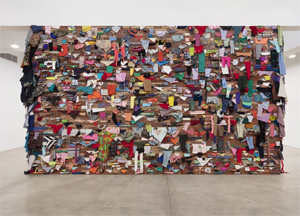

Karyn Olivier is out in front of the headlines. "At the Intersection of Two Faults" opened the very day of a condo's collapse in Florida, and I had to look twice to be sure that I had not seen her opening photo hours before online. It shows a wall of cinder blocks strewn with clothing, and it could well be collapsing before one's eyes. The collapse seems to extend to nature itself, with a ledge of dark earth in the landscape behind it—and with actual earth layered onto the photo in front. Still more black earth, strewn with confetti, supports a terribly plain folding chair. Before one encounters its darkness or its color, though, one must pass a more formidable wall.

Olivier has a talent for situating her constructions within urban histories and the gallery. She just needs gallery-goers to inhabit them. Her physical wall relies on red bricks, for a touch of local color, running twenty feet across and twelve feet high. Clothing multiples, too, not just on top but between bricks, spilling out every which way. It speaks, too, to the lives of others, in dress clothing, casual clothing, and in rags. Olivier could almost be counting on those lives to hold the bricks together in place of mortar.

Olivier has a talent for situating her constructions within urban histories and the gallery. She just needs gallery-goers to inhabit them. Her physical wall relies on red bricks, for a touch of local color, running twenty feet across and twelve feet high. Clothing multiples, too, not just on top but between bricks, spilling out every which way. It speaks, too, to the lives of others, in dress clothing, casual clothing, and in rags. Olivier could almost be counting on those lives to hold the bricks together in place of mortar.

In reality, though, she relies on the gallery—and not just on you. The wall runs up against a ceiling beam, which determines its height. Is Fortified a barrier or shelter from the storm, in a gallery that began the year with a one-room building in wood by Haim Steinbach? Neither all that much, for one can walk around it to see more, limiting its width. It is also just a wall, with clothing overrunning its back, completely obscuring the brick. Still more clothes hang down from a fence post, while a bright yellow hoodie has adopted a coal shovel as a coatrack.

Olivier has mined the site specific and the city's past since she ran tracks through the basement of SculptureCenter, a former trolley repair shop, in 2004. She aligned appropriation and the handmade the next year, too, as an emerging artist in "Greater New York," with a column of furniture. She brought her greater New York to the Whitney and as an artist in residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem in 2006. One could admire her jungle gym in both sites for its polished construction, its wildness, or its familiarity. One might have to leave playtime to imagined others, but her urban histories are open-ended, like urban life. They have become more diverse and colorful in the years since, with all that clothing, but she still prefers black tar and black posts to grass and trees.

They are also closer to disaster. For all the scraps of clothing, a yellow clothesline hangs empty apart from a gnarly scrap of wood. One might mistake it for a bone from a dead animal or a fossil. She may have her maritime disaster, too, with buoys hanging down over the tangle of rope from a lobster trap, as How Many Ways Can You Disappear. An artistic disaster might be lurking as well, in ornate picture frames devoid of pictures and sliced in two. She has painted them white, like the wall, because history and its unraveling begin here, in the gallery.

Summer group shows have grown tamer in the wake of the pandemic, most of gallery artists. Upstairs, though, her gallery adds another impressive urban history. Curated by Keyna Eleison and Victor Gorgulho, it reconstructs the scene around Teatro Experimental do Negro and its founder, Abdias Nascimento, in Brazil. It has its memorabilia, but it brings that black experimental theater into art as vivid as the present. "Engraved into the Body" runs from video of male nudes and of burning, recalling protests against a repressive regime, to abstract sign systems and portraiture akin to Alice Neel. Faced with so many unfamiliar names, I hate to single anyone out for praise. Just be aware of the many ways to engrave male and female, black and white, politics and art, into the body.

Have a seat

By the time you read this, New York City may be almost back to normal, but not the atrium of the Museum of Modern Art. To be sure, as I came to check out Amanda Williams,  normalcy seemed ever so far away. I could still have had Vincent van Gogh and Starry Night to myself, like van Gogh in Saint-Rémy, along with the rest of the collection. A curator engaged a visitor in conversation, with the leisure of a member's only Monday morning. Eager to accommodate the few who dared to appear, a guard pointed me toward a seat. And Williams offers no end of seats, only not for the likes of you and me.

normalcy seemed ever so far away. I could still have had Vincent van Gogh and Starry Night to myself, like van Gogh in Saint-Rémy, along with the rest of the collection. A curator engaged a visitor in conversation, with the leisure of a member's only Monday morning. Eager to accommodate the few who dared to appear, a guard pointed me toward a seat. And Williams offers no end of seats, only not for the likes of you and me.

With her installation, MoMA takes a provocative step backward after the lockdown—and a step toward museums after Covid-19, when Adam Pendleton will soon turn the same space into a street theater. You will know it all too well from schools and other institutions during the lockdown. Furniture piles high, culled from every corner of the galleries, sorted and neatly stacked. MoMA's 2020 reopening in the pandemic was freewheeling, at the cost of nothing new in that two-story atrium. Haegue Yang, a holdover from the monster 2019 expansion, aimed for unbridled pleasure, with arbitrary color, shapes, and glitter across the walls. It could well stand for the limitations of that expansion, and so could the museum's block-long lobby, practically empty for now and devoid of purpose. A floor above, Williams takes stock.

Still further upstairs, as "Reconstructions," she and other black architects take stock of how race enters into the decisions that shape cities. Here, too, she says, she wants to know "who has the freedom to move, and why"—and "who has never been free to move at all." You might find the leap from used sofas and chairs to racism a bit of a stretch. You might find the obstacles of her own making at that. Signs on the desks still promise admissions, free audio, and a safe place to return it, even if she does not. They are massive obstacles all the same, and many a museum or library atrium could learn something.

Her title speaks not of furniture or modern art, but "Embodied Sensations." Williams also takes stock of MoMA's design sense, in a museum long devoted to architecture and design. That devotion becomes all the more palpable apart from routine exhibitions of fancy objects. She cannot include a genuine Marcel Breuer chair, but she makes clear how he and others have enhanced the museum experience. No surprise that everything here is black. With a sleek modern interior and an African American contributor, black is the new black.

She takes stock, too, by asking visitors to measure every step. Wry guidelines on the floor tell you where to begin and when you had better "move to somewhere else." A slide show runs continuously, with more directions. Some take the form of diagrams, like choreography but funnier. "What are you afraid of," and "how much personal space do you need?" Do not answer too soon.

Other questions might belong to a party game or an IQ test, and you can settle in for the challenge. (Two chairs at a circular table near the projection are the show's one allowed seating.) Race is implicit again with the text of what appears to be voting-rights legislation, although it would take a sharper legal mind than mine to know whether it quotes efforts to expand or to restrict voting, which I suppose is the point. Again, Williams is asking a lot to pin things on MoMA and you. Still, the atrium may never work all that well for art, however creative, and social distancing may never again seem so embodied. For now as well, thanks to Williams, it leads directly to the collection and to the return of a museum.

Lucy Raven ran at Dia:Chelsea through December 30, 2021. Karyn Olivier ran at Tanya Bonakdar through July 30, 2021, Amanda Williams at The Museum of Modern Art through June 20.