Minimalism as Ritual

John Haberin New York City

Zarina Hashmi and Huma Bhabha

Zarina Hashmi and Huma Bhabha are of very different generations and hostile nations, but in place and spirit not so very far away. One is from India and one from Pakistan, both are women and in New York, and both connect Minimalism and biomorphic abstraction to harsh rituals. In different ways, they ask when terror and loss translate into something spiritual, personal, and true to the present.

Mapping memories

In 2001, Zarina Hashmi laid slim black strips of varying lengths, end to end, across a horizontal sheet of paper. Their zigzag course could have arisen by chance, in tribute to Surrealist drawing, or by fate. Indeed, it looks like nothing so much as a mathematician's random walk. Or it could follow the rough but steady course of nature, in her native northern India or her adopted land, the United States. Another work from the same year, Dividing Line, has the broader but gentler weaving of a river. A woodcut, it also stains the handmade paper, mounted on a second sheet, with short black traces like the weathering of a great plain.

In reality, those black strips graph the artist's westward travels, for all her debts to Indian art. The course of her life, too, could have been far more purposive than she lets on—or a surrender to the future. She had married a foreign service officer in 1958 and followed him on his changing assignments, feeling always and never at home. One might well miss the work entirely on the way to something grander on the museum's ramp. Yet it has a central place in her modest retrospective, both in time and on a freestanding wall. She calls it Mapping the Dislocations.

Zarina, as she prefers to be known, may well have executed the work before September 11 of that year. (So we are on a first-name basis already. How nice.) Still, she has acknowledged how much the day has meant to her, and so much of her work is about dislocation and disaster. Shortly before, she made a print about the loss of her New York studio. Soon after she began a series, . . . these cities blotted into the wilderness, in which the lines map the course of war, in Bosnia and elsewhere.

One of her earliest works, from 1977, came after the death of her husband. The patterning, left by ordinary pins piercing paper, goes just fine with the abstraction of the time. It approaches the rule-driven procedures of Sol Lewitt, much as a pure white composition of nothing but folded paper is so close to Dorothea Rockburne. Paper pulp molded into a picture frame has the thickness of Ralph Humphries, while more paper pulp cast in bronze shares its biomorphic shapes of petals and cocoons with Eva Hesse or Alina Szapocznikow not that long before. At the same time, the obsessive act of creation is like the ritual of grieving. More recently, Zarina has carved fine soft wood into Muslim prayer beads.

Maps and rituals are forms of restitution and control. Simply in mapping the dislocation, she locates it. (From another series not at the Guggenheim, Cities I Called Home, I can safely say that her New York home is Manhattan.) The handmade paper derives, naturally enough, from south and central Asia. Other works, too, are suspended between loss and recovery. Some incorporate family photos, while the 1991 Letters from Home start with actual letters between her and her sister, about memories of their parents.

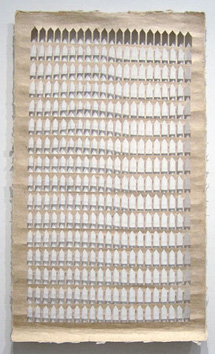

Along with maps, she embraces architecture. The thick black lines on her letters from home amount to floor plans. Cuts in gold leaf on paper make it look like piled bricks. Shadow House I of 2006 consists entirely of a cutout, with each gap in the shape of an arch, while the whole could function as a window. Each arch casts shadows like a larger structure as well. One way or other, the artist has found a home.

Back to the future

Zarina places herself between contemporary art and tradition. She likes to describe herself as a carver rather than printmaker, and the large hanging of gold leaf would look at home in the Met's Islamic wing. The first prints one sees, from 1996, include a single line of Urdu poetry, as textual as an illuminated manuscript and as spare as Minimalism. Even the paper architecture recalls the great age of Islamic art, in which a diagonal can stand at once for perspective, the corner of a building, or line itself. Zarina's early work looks back in another way as well—well past Minimalism, with black rectangles tilted as for Liubov Popova and Russian Constructivism. One can see why she appeared before at the Guggenheim, in "The Third Mind," about the meeting of Western art and Asia.

She is seeking a place between the spiritual outside of time and the facticity of the present. Those are her real feelings, but also real travels and real cities, damaged but with survivors. In Chelsea, her mix of representation and abstraction can easily blend into the polish of an upscale gallery. She thrives in a museum, where one has time for associations. In the past, I could hardly feel the loss. Now I could start to see how she gets past it.

The curators incline toward the present. Allegra Pesenti of the Hammer Museum in LA, with Sandhini Poddar and Helen Hsu of the Guggenheim, use the main room for the 1990s and, even more, the last decade. Their choice makes the older art into a kind of background, as if you and they together were reconstructing a career. If you enter the tower gallery after walking up the ramp, rather than down, it can come as a surprise that Zarina even has a background. Sure enough, she was born in 1937, to a Muslim family, and moved to New York in 1976. The oldest work here dates to 1961.

Within a room, too, the arrangement departs from chronology, but it does well by the artist. A circular glass table adds drama to a display of small sketches. The partition for Mapping the Dislocations creates a small back room, covered with small tin cutouts. Up close the bent metal looks like masks. Step back, and they cross the curved wall like a flock of birds. Either way, the work looks downright site specific.

It also starts darkly and then takes flight. Zarina loves antimonies of light and dark, redemption and loss. The gold leaf of Blinding Light hangs next to the woven strips of Dark Night of the Soul. Still, something in her just will not incline to darkness and disaster. Her blackest work blends in obsidian dust, so that it glows. And I remembered most the gold.

The curators call the retrospective "Paper Like Skin." The title pays tribute to the many textures of its paper and their personal meanings to the artist, but it implies raw pain that just is not there. Zarina leaves a black hand print as one drawing, much like Siobhan Liddell, but she is hardly flayed and skinned. Her rubbings are of branches, fallen in winter but waiting for fresh growth. The paper is not her body but her field, for rebuilding and memory. It brings the marks of her past into the present.

What we worship

Huma Bhabha did her shopping early and often last year. And to judge by her solo show, at MoMA PS1, the tastes of her family and friends run to toys and electronics. Others must settle for the empty Styrofoam casings—or worship them. Her sculptures stack and hack into dozens of them, as totems beyond a chain store's wildest dreams. Empty or not, they contain multitudes, in scraps, bones, horns, chicken wire, and clay. She calls them "Unnatural Histories," but do not be surprised if they also contain hoopla disguised as history.

One can appreciate the sheer scale of the title sculpture, made for the exhibition and in its central gallery. A gaping eye takes much of its flat face, like a fallen idol that still sees and suffers for what it sees. Behind lurks one of the show's rare male presences, a hunched silhouette, and more debris stretches out past that as the road not taken or left behind. It includes a flattened tire, one of Bhabha's few other plainly recognizable materials. It would look quite at home with Robert Rauschenberg, but more often she keeps a distance from pop culture and human particulars. Works do not burst their frame, like his combine paintings, so much as tower above it even while coming apart.

A fine installation invites one close, to examine their scars or to worship, while framing many a frontal view from afar. Smaller icons are on their pedestals, as no doubt they insist, and two more stand cast in bronze in the courtyard outside. Dark scrawls evoke similar figures, painted over photos of barely discernible concrete and rubble. For Karen Rosenberg in The New York Times, they evoke everything from fertility goddesses to "the last vestiges of the human race." For the curators, PS1's Peter Eleey and Lizzie Gorfaine, they are "monuments to human life reclaimed from the detritus of a post-apocalyptic landscape." We are talking serious.

One can understand the bones and clay, for their fragility and associations with archaeology. One can understand, too, the Styrofoam, for its alternately textures and its associations with the present. In bronze, it can look like cinderblocks. Crumbling and worn, it can look a great deal older. It can also look mechanical and repetitive in its primitivism revisited, even at roughly thirty sculptures. Bhabha made all of them since 2005, most in the just the last few years, and she does everything she can to bury their differences.

Born in 1962 in Pakistan, seven years before Shahzia Sikander, the artist hit her stride just when the art scene was moving in her direction. She has earned a place among the women in "Born in Flames," 2010 Whitney Biennial, and the New Museum's "After Nature" the year before—just one show in a wave of what PS1 that year called "art for a forgotten faith." But faith in exactly what? Maybe the vagueness is part of the point—just as for Thomas Lanigan-Schmidt down the hall, who since Stonewall has merged the glitter and excess of Catholic ritual and camp. Bhabha's "neo-primitivism" has a politically correct nod to consumerism, globalism, diversity, and Mideast wars, but with all the superiority and condescension of the primitivism before it, when modern artists and collectors were just discovering African art.

Bhabha looks back to the biomorphic abstraction of Hesse or Louise Bourgeois, while avoiding the breasts and curves that once obliged modern sculpture to confront a woman's experience. Her body parts recall Kiki Smith, Magdalena Abakanowicz, and the Eastern European art later in "Transmissions," but (like Salman Toor as well) without the explicit politics or pain. How could the gods of the art world deign to endure pain? Her sculptures promise grandeur with the imprimatur of rawness, sincerity with the imprimatur of an art larger than life—and often they succeed, but allow me still my doubts. For the curators, "They remind us of what we worship." Speak for yourself.

"Zarina: Paper Like Skin" ran at The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum through April 21, 2013, Huma Bhabha at MoMA PS1 through April 1.