A Portrait of Diversity

John Haberin New York City

Salman Toor, Newsha Tavakolian, and Hana Yilma Godine

Salman Toor has earned a Chelsea gallery and a solo show at the Whitney Museum, but he must wonder even now if a gay Asian male can ever get past the door. Fortunately for him, he has plenty of friends and alter egos to help. He returns the favor by painting them and their lives. Does it matter if they look largely alike or if he made up their stories?

As if in response, Newsha Tavakolian has made her video, in the words of its title, For the Sake of Calmness. She has a long way to go. She must seek comfort for now in enigmatic portraits of people and places in Iran—and of her still anxious self. Does that make her art go down awfully easily, or does she capture that much more the anxiety of gender and race in America and abroad? Hana Yilma Godine paints her friends to much the same ends, in Africa and the United States, but as portraits. Her choice of a traditional genre only enhances her pushing the boundaries of her medium and personal identity.

Under scrutiny

Salman Toor shows a man much like himself, under scrutiny from a TSA agent along with a single sneaker, a necktie, and a small bottle of mysterious liquid. (If I were you, I would be very, very suspicious.) The other sneaker may lie just outside the frame, or it may be lost to him for good, and he will be hobbling as best he can to his flight and his destination. The visitor in The Arrival has arrived, but he has not altogether crossed the threshold, and he may doubt that he ever well. The man on the inside has one hand on the door, even as his outstretched arm presents a barrier. His other hand reaches out, whether as a rebuff or a gesture of affection, but his guest, facing the viewer, is not confident enough to return his smile.

Not everyone passing through security must take off his tie along with his shoes, but Toor expects a heightened scrutiny. He may consider it his business at that, as an artist. He shows a star in his dressing room while others apply makeup, and neither they nor the painter will let go. It may be worse still when no one is paying attention. A man with face creams and a phone plug on the table before him cannot disguise his slumped shoulders, dissolute expression, or lack of communication. A "bar boy" shows off to a crowded bar, but as the sole figure without a companion.

Not every painting shows what a student of urban architecture might call transitional spaces, like a doorway or an airport. Two follow men into the bedroom, like classical nudes from Titian to Edouard Manet. One welcomes a silvery shower of light, like the golden shower with which Zeus impregnated Danaë, but he is only looking at his cell phone. The other has fallen asleep at his laptop. Can a gay Asian American artist get away with what, in a different painter with a different subject, would be the exploitation of women? No doubt, but these men are literally up to their own devices.

That tension dogs an artist still in his thirties, but it helps him as well. A mere fifteen works in the museum's lobby gallery, ten made just for the show, have a fashionably slapdash realism. He makes a point of his youth, even as, at his age, he has passed the bar. That sneaker is a Van, the maker of footwear for skateboards, and everyone spends every spare minute checking the phone, even in intimate couples. And yet the intimacy and its threats are the point. Toor's subjects may be partying or hanging out together on a stoop, but are we having fun yet?

The show's title leaves things just as uncertain. "How Will I Know" is missing its question mark, as if he were merely texting, but he would very much like to know. Wall text calls his settings lush because of all the hardware, but who today is not plugged in? The brushwork may be lush, too, but it may leave backgrounds gray and unfinished, with at times nary a window or interior decor in sight. More often it bathes the entire painting in green, leaving his subjects in an awkward space between warm and chilly, old and young, indoors and out. When they are not checking the phone, one half of a couple may be kneeling, but whether in dancing, in dirty sex, or in desperation is never altogether clear.

Toor bases them on himself and friends, with the TSA agent as young and casually dressed as his suspect. They become his fantasies or his fears all the same. Roughly half have long, thin noses—because they have become his 'toons and because Pinocchio has told a lie. Born in Pakistan (like Imran Qureshi and Huma Bhabha), he identifies as brown but sets only one work in Asia, a tea party. Of course it, too, is a social scene in a society with its own rules. He left me unconvinced, but he knows the scrutiny and the rules.

Keep calm and carry on

Stills from the video by Newsha Tavakolian are a beauty, in rich but quiet color. The bright, even tacky hues of an automobile for a pioneer of color photography like William Eggleston, pastry in a diner for Garry Winogrand, or a crisis point in the Middle East for Stephen Shore seem far, far away. One has instead a living room filled with memories and a city darkening into sunset. And yet the living room has become stifling, with a curtain cutting off the window, and the meaning of old photos to either side is lost.  Any remaining light on the horizon sinks houses before it in darkness, and whatever covers flowers in the foreground increases their mass and stifles their color. Has no one told Tavakolian that plastic bags are an environmental hazard?

Any remaining light on the horizon sinks houses before it in darkness, and whatever covers flowers in the foreground increases their mass and stifles their color. Has no one told Tavakolian that plastic bags are an environmental hazard?

Of course, someone has, which must be why she chose them, to lend the park its chill. She cherishes the chill quite as much as the low, dark skyline of the city she knows best, Tehran. She cherishes, too, barren earth seen from above, with people crossing every which way and none. They are dwarfed by their own long shadows, and what accounts for the still larger dark outlines on the sand? They must be shadows, too, of trees or telephone poles, in a city of ghosts. Here ghosts alone can keep calm and carry on.

On video, calm seems that much further away. Time may be the work's true subject, and it weighs heavily. Things proceed mostly in slow motion, like the people crossing—or the pendulum clock behind a woman at a kitchen table. Her lips do not move, although a narrator that plainly identifies with her keeps talking. Slow motion alone can account for the immobility of a couple in that living room. They share a sofa just big enough for them and their memories, but facing front and forever apart.

Time must surely weigh heavily on a younger man with a scruffy red beard and a loose shirt or jump suit, like a prisoner. The tiled walls do not look comforting. In the video's one exception, sunset is sped up, so that darkness comes all the sooner. The flowers and their plastic sway quickly in the wind or in a bad case of nerves. Whether too fast or too slow, the passage of time is itself confining, and Tavakolian's narration finds confinement everywhere. The people crossing may be in a hurry, but they must look straight ahead, she says over and over, because the air to either side is too polluted to breath.

If things are going nowhere fast, one could say the same about the video. Its nineteen minutes divide into a good dozen episodes, with no obvious arc or connections, and why not? Lives here may well be too private to connect. Tavakolian says that she is describing her own states of mind with PMS, and politics seems off the empty table. For all I know, his clothing may mark the young man as a health-care worker—not that comforting a prospect either after Covid-19. Who am I to know how Iran dresses its prisoners?

Still, it is hard not to take religious and political oppression here as a given—quite as much as for an Iranian artist like Shirin Neshat, Asal Peirovi, Ardeshir Mohassess, or Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian. One had better, to rescue the artist from self-involvement. The narration can grow ponderous in no time. Pollution is unbearable, the skin on her wet feet is cracked, and condensation is about to swallow her alive like an evil demon. You may lose patience after just a few episodes. Still, you can appreciate their oppressive beauty.

A space for friends

Hana Yilma Godine knows how to paint big: take it one person and one observation at a time. She calls a show and most of its works "Spaces Within Spaces," and she needs every one of those spaces to accommodate a woman's life. Born in Ethiopia, she has traveled widely in Europe and America. She travels more widely still between early Modernism and today. She is no refugee, though, and her women are among friends, even if never quite at home.

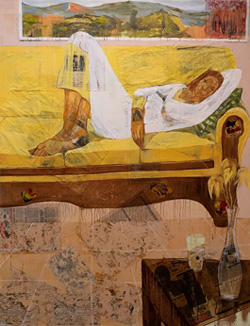

More than one rests on a sofa, in some of her largest works. They are taking their ease, alone and with you. Still, the landscape behind them seems ever so far away, and the plunging perspective sets them apart from the still life before them as well. You can step closer, hoping to make sense of it from a point of view within the painting, but the space does not so easily become yours. You almost surely cannot understand the newsprint beneath one woman, at once still life, the carpet, and the painting's ground. She may be too restless to read it herself, like the recumbent woman in another work clutching her phone.

A sheer fabric hangs on the wall as backdrop and extension, swaying as air circulates in the gallery as if blowing in the wind. The curtain will never close upon the painting or open to reveal it, as in the illusions of Dutch painting and trompe l'oeil. One thing, though, is for certain: Godine's subjects are herself and friends, much as for Jordan Casteel. Sometimes they come together, seated side by side or over a table, just to talk. Others sit alone facing front, as if talking to you.

They will have a lot to talk about. Godine seems reasonably indifferent to global politics, but she is claiming art for women and diversity. She describes Addis Ababa as a multicultural city, counting past cultures as well as present diversity. She studied, after all, at the Abyssinia School of Fine Art. She cites multiple traditions within Ethiopia, including Biblical art, while the techno buzz of Afro jazz plays in the gallery. Western art may still treat African woman as doubly exotic, like Morocco women in a harem for Eugène Delacroix long ago, but here the exotic is now.

She borrows flat, muter tones from Paul Gauguin and heightened colors from Henri Matisse. Matisse's woman on a high, stiff chair inhabits one work, but whether on the wall or in the room I do not know. A woman's hand takes on still more tones from the dress visible between her fingers, and that silken fabric could serve as wallpaper. The very need to take a portrait stroke by stroke, in the paint or in the mind, goes back to Paul Cézanne. If Godine hardly knows whether intimacy will win out over distance, Cézanne could have said the same about portraits of his wife. Yet she paints everyday life in the present, and the language that you cannot read has the last word.

Strong colors and strong displacements mean strong feelings. A casual conversation on one side of a painting veers into acid reds on the back—so much so that I mistook a women for hiding her head in tears. The gallery speaks of each work as hung differently. That one hangs from the ceiling to expose both sides, while others sprawl across more than one canvas. Still, the strange cohabitations within a painting count most. When she returns to Ethiopia, she will remember a kitchen table in Boston, but also the collisions of spaces and spaces, friendships and isolation, anxiety and joy.

A postscript: salons and trampolines

Not two years later, Godine is back, this time spanning two galleries, for "A Hair Salon in Addis Ababa." That alone suggests her ambition, and so does her increasing reliance on diptychs and triptychs. She may devote a part apiece for a woman or span parts in unexpected ways. The play between flatness and perspective also adds more than ever to the unexpected, with sunny skies that may appear at the top of a composition but also below. These are just friends, but Godine's personal life spans continents and painterly spaces. It also spans feelings, from stern women that refuse to boast to the broader world that they inhabit.

Rather than try to review her from scratch, at least so soon, I can only ask that you rely on my past review. A postscript, though, can spotlight her growing attention to the ground and, with it, subjects beyond black portraiture. Some grounds, unstretched and loosely stitched to a frame by threads up to two inches long, reflect a fashionable interest in weaving and the decorative arts, but not only that. They may hold a still life—large, bright, and up close, its presence only an illusion but still no less real than the ground itself. The ground and its unconventional attachment looks even more like a trampoline. Godine may seem like the last person to let loose, but she and her circle are having fun.

Salman Toor ran at The Whitney Museum of American Art through April 4, 2021, Newsha Tavakolian at Thomas Erben through February 13. Hana Yilma Godine ran at Fridman through November 1, 2020. Godine returned at Fridman and now also Rachel Uffner through March 5, 2022.