Do Not Touch

John Haberin New York City

Louise Bourgeois

The Guggenheim has a way of setting art off-limits. Try to get too close, and the sloping floors keep one from the walls. Try to step back for a better look, and one might plummet over the railing and into the rotunda.

Louise Bourgeois more than belongs in this museum. She does its work. Who needs guards? Around her objects, one has to tread very, very gingerly. One might fall into a few traps all the same.

For a self-styled matriarch, Bourgeois has made some of the most approachable art of the twentieth century. In the late 1940s, she collected scraps of wood from the street, hacking them away almost carelessly, stacking them as she may. At ninety-six, she adjusts to the limitations of age, with Cells and stage sets of weathered doors, postal sacks, and bruised fabric. In between, she gives cast bronze the unfinished look of plaster and modeling clay. She makes objects so seductive that one can hardly help wanting to enter—and to touch.

Anyone could do this, if only one had her ease and freedom. It has made her a model for so many artists and so many styles of art. Better yet, make that a temptation for so many. In her retrospective, one wants to do more than approach the work. Again and again, one wants to touch. If only one dared.

The ego and the id

Early wood totems by Louise Bourgeois do gather behind a barrier, like a cross between a forest and a clown show. Their slim, verticals recall Constantin Brancusi and Isamu Noguchi: like the two older artists, she eradicates the distinction between art and the pedestal. Much of her sculpture, however, sits comfortably in the middle of the ramp. It can look after itself.

Increasingly, she erects physical barriers, but of another sort. A 1997 Spider occupies a metal cage, threatening both to confine one in and to keep one out. The Cell doors, mostly from the 1990s, form closed arcs—with a dead end where one expects a glimpse or an entry. A second path allows a view, but visitors peer anxiously through keyholes and gaps between doors, like voyeurs. The Confrontation of 1978 has an ironic title given the surrounding white oval, like a barrier to car bombs. Its parts might resemble caskets, more doors, or a building blown apart by whatever is taking place within.

A compulsion to look, to touch, and to withdraw comes even without the cage. The urge starts with the imagery. Spidery legs reach out with their ghostly, maternal shadows, but who really wants to pet a spider? Who wants to be caught stroking a penis in a museum? (Well, speak for yourself.) Just as much, though, comes from the art object.

Like the cast bronze, Bourgeois's sculpture seems soft where it should be firm and firm where it should be soft. Fabric lovers look like diving suits. Pink marble looks like resin. More polished marble rests on timbers. Still rougher, mottled marble culminates in shiny vertical tubes like undersea vegetation. Better draw your hand away before it moves and grows.

One could identify the temptation with the id, the taboo with the superego. Freud is smiling, but so is the artist (and do check out a review of Bourgeois as "Freud's daughter" for more than I can include here). The limp and erect tubes put "penis envy" in its place. Arch of Hysteria, from 1993, refers to a supposedly female disease, but the bronze suspended from the ceiling depicts a flayed, headless man. Just as important are the jokes and craft behind the pain and impulses. They speak for a third, sometimes conscious component of the psyche—the ego.

No one could accuse Bourgeois of lacking an ego. She has cultivated a personal history and an iconography, not altogether at odds with her elegance in photographs. Love, hate, or ignore the myth, this art is about myth making. A similar bow both to the biomorphic and to Minimalism, by Anish Kapoor, seems downright modest by comparison.

Mothers and fathers

A name like Bourgeois sounds almost comically mainstream, and so might her life. She left France in 1938, settled near Gramercy Park, had three children, and continued to work up on the roof. Born just months before Jackson Pollock, she falls between generations as between countries, but she spans them, too. Her husband, Robert Goldwater, argued for a relationship between primitivism and modern art. She has experienced American Surrealism, global Surrealism, and the European kind, Abstract Expressionism, Minimalism, and everything since at first hand. Increasingly, they knew her as well.

Bourgeois dismisses the label feminist, but not her influence as artist and role model. Thanks in part to Lucy Lippard, the critic and activist, she came to attention at Fischbach Gallery, where Eva Hesse later showed. She had the conflicts of a working mother and once marginalized artist, and she has depicted them with her Femme Maison—ambiguously woman house or house woman. She received a defining 1982 retrospective at the Modern, moved to a larger studio in Brooklyn, and continues to make art to this day. She has the only solo exhibition covering sixty years that I may ever see.

All that leaves out the neuroses and the naughty bits. Like Henri Matisse or Matisse's favorite patron, she has roots in the textile business—but with battered textiles and links to much older art: her family repaired tapestries, while Matisse's textiles were a family business. She has said that the job often attended to a worn bottom edge, where tapestry rubs against the ground. Perhaps it taught her that art should begin with its base. Perhaps it taught her that, as for Rosemarie Trockel, art is always unraveling.

All that leaves out the neuroses and the naughty bits. Like Henri Matisse or Matisse's favorite patron, she has roots in the textile business—but with battered textiles and links to much older art: her family repaired tapestries, while Matisse's textiles were a family business. She has said that the job often attended to a worn bottom edge, where tapestry rubs against the ground. Perhaps it taught her that art should begin with its base. Perhaps it taught her that, as for Rosemarie Trockel, art is always unraveling.

On video, a fashion show involves bulbous clothing of her design. And who is she to object if the models look silly and pretentious—and the male judge in sunglasses looks even worse? Her retrospective at the Guggenheim translates one title, Fée Couturière, as seamstress fairy, explaining that it also puns on the name of a bird. I might prefer fashion fairy.

Her father's cruelty and affairs destroyed the comforts of home. Bourgeois has insisted on that psychic scar as the key to her art. She called her first large-scale installation, a glowing red Last Supper or mushroom garden, The Destruction of the Father. She relates the work to fairy-tale archetypes, of children ingesting the father. In The Confrontation, a long, thin stretcher evokes a funeral ceremony for a dismembered body—or an oven tray for rising bread. Still other work represents Freud's "primal scene," of adult sex through the eyes of a child.

The myth can easily verge on psychobabble. As with Louise Nevelson or Yayoi Kusama, I often want to put one thumb to each ear, wiggle my fingers, and make scary noises. It may or may not matter that I cannot see the fairy tales in the bulbous mounds of her work. It may or may not matter that Freud's primal scene concerns parents having sex, not a father's rejection. Sex with a mistress only postpones the primal scene, and the daughter could never have witnessed it. Or do all the deferrals of love, sex, and witnessing heighten the psychological tensions?

Fiction and repetition

Freud introduced another idea relevant to both neurosis and art, repetition. One can see the secrets within the Cells, like the pillow embroidered Je t'aime, as a return to childhood or a final emotional release. One can see their mirrors as inner reflection or outward projection. In fact, one can look at Bourgeois's entire long career either as constant repetition—or constant reinvention. It is not easy to decide, and the conundrum helps explain her extraordinary psychological weight and range of influence.

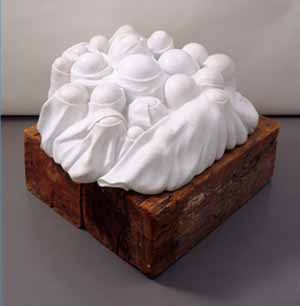

The same titles recur decade after decade, as do much the same images. The first spider and the first Femme Maison date to at least as early as 1947. Other favorite titles include Lair and Cumul—those shrouded, fishlike penises that never quite dissolve into clouds. In the process of repetition, too, images become unmoored from Freudian stereotypes. One frontal sculpture could have knees, legs, petals, or vulvae, but never a vagina dentata. Knife Woman responds to Spoon Woman by Alberto Giacometti, much like Barbara Chase-Riboud, and who can say who suffers under the knife?

One could also point to a succession of styles. One could also ask oneself exactly what else is happening in the art around her as one ascends the ramp. The game makes a good reminder of her place within and outside a century of art movements. At Dia:Beacon, she appears alongside Minimalists, and suddenly the stacked, repeated forms and the metal cages make an even stranger sense. Last year at her gallery, she appeared alongside Lynda Benglis, and the phalluses made her an archetype of feminism and Post-Minimalism. Each time, she gets along just fine while insisting on her own myth.

She starts her career as a painter, with biomorphic forms, floating or falling people, and flat, bright colors. They echo Max Ernst or Joan Miró and Miró's Dutch Interiors, but with a woman as protagonist. The early totems relate to Goldwater's primitive and Surrealist Personages as well as to Brancusi. However, they have a comic realism, like a Parisian street scene. Horizontals can morph between arms, wings, elaborate hats, and loaves of bread.

The stacked, found units also look ahead to Robert Rauschenberg, Rauschenberg among friends, and his combine paintings, to Minimalism, and to conceptual art, and so does her use of text. However, Bourgeois has scant interest in popular culture or industrial parts. The nostalgia for the handmade continues up to her late Cells, with ordinary doors and glass vials in the interior. The glass may refer to perfume and to a woman's masks and identities, but also to ancient hospitals and laboratories. Besides, if this were Minimalism, one could indeed touch the art.

The late Cells and installations also foretell the decrepit structures all over art today—from "Unmonumental" at the new New Museum to the 2008 Whitney Biennial or Gedi Sibony. They remain, however, self-contained tableaux with stories to tell. In between these early and late stages come all the private parts. The appearance of rough plaster in Lair stresses again the opposition of a shrouded interior and a tangible surface. Bourgeois's spiders could be birthing within. This is territory for Hesse, Benglis, Kiki Smith, or Robert Gober, but with a classicist's marble and bronze in place of latex and threads.

Kicking against the pricks

The Guggenheim has the advantage of twenty-five years since her MoMA retrospective. It has the disadvantage of little urgency, plus the biases of later years. The show, which originated at the Tate and the Pompidou Center, gives way too much space to the Cells. It runs away from the spiders as from a plague of locusts. The caged version remains at Dia:Beacon, and one could almost miss a large one out of its cage by the ticket counters. The most prominent work, The Confrontation, naturally spotlights the Guggenheim's permanent collection.

Wall labels are too small and irregularly placed for easy reading. They also dwell on questionable interpretation rather than information. They rarely translate Bourgeois's French titles, which must puzzle at least a few visitors. Still, for once the Guggenheim is not just showing an artist—a woman artist at that. It is showing decades of change in art. Her small sculpture hanging from the ceiling weighs more heavily than another Cai Guo-Qiang exploding car.

The ramp ends at the top of the rotunda, and one can imagine the artist still at work in the chamber behind the closed passage. It leaves her a riddle, which should make her very happy. It still has one making sense of the Surrealist who, by accident or intention, fostered feminism and Postmodernism. One clue lies in the repetition and the change. Maybe another lies in the objects that one fears to touch.

Bourgeois may look indifferent to craft, even once one notices the smooth marble and the surging bronze, but the awkwardness masks a serious concern for visual and tactile surfaces. When David Smith was "drawing in space" or in white sculpture, she was filling and contracting volumes. When others were making abstraction, she was creating illusions. Most of the time, the illusion points to the surface.

In her hands, painted wood can pass for stones and shells. The standing Personages rise on their shafts like necklaces on string. Over time, her materials become lavish, like marble, but also more explicit. She returns to older subjects with a grater eroticism and terror. A famous artist could afford more. At the same time, by the 1970s explicit desires had started to speak their name.

Bourgeois gave to a younger generation and a changing culture, but she also took something. That attests again to the power of the conscious ego. Where a Surrealist digs for ambiguity deep in the mind, Bourgeois has her comedy of the human. Spiral Woman of 1984 wraps bare legs in a bronze cocoon. It could be burying her in another spider's web—or choking her in a spiraling penis. It could be identifying her swelling belly with organic nature. Then again, she could just be kicking against the pricks.

Louise Bourgeois ran at The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum through September 28, 2008. Related reviews look at Bourgeois prints and psychoanalysis and at Bourgeois as a painter.