Minimalism and Excess

John Haberin New York City

Joseph Zito, Dwyer Kilcollin, and Annette Lemieux

I remember Mammy. I wish I remembered Joseph Zito some other way, but this work has a way of getting under one's skin. Three cookie jars, in a form still recognizable from the likes of Aunt Jemima, hang like a single chain from the hand of a strikingly white lawn jockey.

It sounds strange coming from an artist with roots in Minimalism, but Zito lived and worked through a decade or two of appropriation and critique as well. Maybe the combination is why I remember it, even while stumbling on more. Younger artists, too, are combining minimal shapes, industrial processes, body imagery, and personal narratives as sculpture. For him, the narratives often relate to childhood, while for Dwyer Kilcollin they suggest a post-industrial landscape. Both are rediscovering Minimalism as part of their own past.

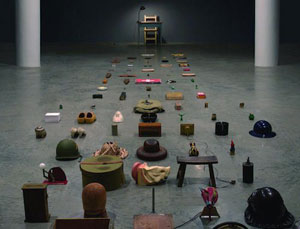

Annette Lemieux could have called her installation Things to Walk Away From, but then she does not so easily walk away. She says that she had to confront the contents of her studio on moving to a new one, and it must have taken some doing. Her ninety-six objects, like a world map, have long since lost their use or even significance. Many have fallen into a musty decrepitude, like a lead toy soldier or felt hat box. They seem all the more distant when, like an old clock, they still function. She might have been collecting them from before she was born—but hold that thought, while I return to the others.

Growing up with Minimalism

Remember Mammy? There is more to Joseph Zito than a lawn jockey, and part of getting to know his work is learning to forget. He has never altogether abandoned sculpture, even in what might look like appropriation. Willie Cole has since brought that one icon up to date, as an African divine messenger, but Zito's has never left planet earth. Rest assured that he has cast those jars in bronze, and, his gallery swears, they "yield a lovely bell-tone when struck with a wooden mallet." I can hardly wait.

In fact, he has been getting under one's skin for some time now, in what a show calls "The First Thirty Years." The very title has the phony ring of birthday reassurances to the elderly, although the artist is still in his fifties, with room to grow. He also chooses his targets carefully, based on what gets under his skin. Zito grew up Italian American in the racial mix of Brooklyn, where he still lives and works, and he hit upon Mammy while nursing his outrage at the racism disguised as scholarship of The Bell Curve. A seeming abstraction of five rectangles from 1992, My Weight in Lead, is just as impersonal and just as close to home. They, too, descend from a single point on the wall, connected by wire that trails off unnervingly close to the floor.

Does Mammy hurt so much because it appeared in 1996, between the all-absorbing irony of Richard Prince and the cynicism of Jeff Koons? It came between two distinct bodies of work for Zito as well, neither one much concerned for popular appeal. Taken together, they challenge one to make connections. They begin in 1985, with First Cut, maybe because the first cut is still the deepest. It consists of a single slit in the wall, barely three inches wide and eighteen inches tall, lined with steel. Yet things really get going in the 1990s, in what became his first show with his present dealer, then in Soho.

The rusted steel and lead share their edge and materials with Richard Serra—but also their intimacy with Richard Tuttle, their care with Martin Puryear, their deliberate clumsiness with Joel Shapiro, their semblance of household furniture with Robert Gober and Doris Salcedo, and their body imagery with Post-Minimalists like Eva Hesse. Seven spikes rise from the floor, leaving one to decide between focusing on the danger of their points or the regularity of their tilted rows. The bottom few inches of each spike have lost their sheen, connecting them by an imagined polyhedron in brown. Two weathered copper disks, bound together, could be primitive armor, lethal weapons, or a body coming apart. In each case imagery is at most implicit, and metaphor is out of the question. All that changes after Mammy.

The concern for raw materials does not change, and neither does the damage they can suffer or inflict. A ball of shining steel rests trapped in a network of rusted steel rods. They do, though, become instantly recognizable—and pointedly unlike the thing that one recognizes. The gap between image and object may lie in materials, as with rose petals spilling out from an opaque glass helmet onto a steel slab. It may lie in the dimension of time, as with an hourglass with red sand that refuses to trickle down to a matching red base. It may lie instead in scale and space, as with small chairs poised unstably.

The concern for raw materials does not change, and neither does the damage they can suffer or inflict. A ball of shining steel rests trapped in a network of rusted steel rods. They do, though, become instantly recognizable—and pointedly unlike the thing that one recognizes. The gap between image and object may lie in materials, as with rose petals spilling out from an opaque glass helmet onto a steel slab. It may lie in the dimension of time, as with an hourglass with red sand that refuses to trickle down to a matching red base. It may lie instead in scale and space, as with small chairs poised unstably.

The materials and their scale may allude to childhood, like a drapery of infant body bags and an inflatable backyard pool holding only iron weights. They may allude, too, to an always uncertain passage to adulthood, like the hollow keel of a single ship as Adrift. They most certainly draw on the artist's everyday surroundings, like a red armchair from his studio cast like statuary. They may border on the obvious, especially when the artist reaches for words and one learns that the hourglass is Stand Still Goddamn It. Another chair turns slowly on its side, the time of its descent taken from bodies falling on 9/11. They are spare and pointed all the same—enough that I may finally forget Mammy.

Beggar's banquet

Sculpture for Dwyer Kilcollin is an accretion. It grows slowly in her hands, layer by layer, and each layer sparkles. One can imagine its growing on its own, like coral. She thinks of her largest work as a banquet table, but it might have taken shape before humans were around to plan for dinner. Even now, it looks stark and empty. Be prepared for a beggar's banquet.

A smaller sculpture on the way in looks both overflowing and ever incomplete. Not quite a sphere, it consists of small, thick, layered sheets like flower petals, only flowers do not often become so large. Its blue and white, too, echo flowers and coral, as does its shine. Yet it rests alone on the floor, dwarfed by the open space. One might pause on the way to the back room for what look like two paintings, but they have their share of empty space as well. One might have arrived too early or too late.

The gallery lists the artist's materials methodically, including quartz and calcium carbonate, but never mind. They are sand to you, mixed with pigment. Kilcollin then adds resin as volume and binder, in forms that she peels away before moving on to the next. If the layering suggests 3D printing, she takes that as inspiration, much like Matthew Darbyshire in thermoplastic sculpture. The computer serves as both drafting tool and model for painstaking work by hand. Nothing is either as organic or impersonal as it seems.

The same process goes into the enormous table in back, and again base is inseparable from superstructure. It serves as both site for sculpture and nonsite—that inaccessible thing itself. The forms that make up the largely white tabletop also allow for stains, creases, and a cluster of tall blue standing out from the mostly empty plane. The shapes could stand for wine bottles from that promised banquet, but also skyscrapers forced onto a desert landscape. You may feel excluded even as you and others walk around it. Any spread this large could also be a conference table, in a show titled "Banquet, Conference," if only a gallery's usual gathering of strangers could agree to meet.

Analia Saban, too, allows hard materials and empty spaces a fluid existence. She identifies her gallery as her "Backyard," but it serves more as a dysfunctional artist's or conservator's studio. Photos display storage shelves packed with paint cans, fabric covering thick supports lies up against the wall like a mattress, and black stains have taken over wood that might or might not have become a painting. Slabs of shattered marble drape like towels or tapestries across sawhorses in two majestic rows. They take on additional texturing from the damage. For Saban, originally from Argentina, only a material's function as art holds it together, but somehow that is enough.

Banquets, conferences, and backyards are all sites of excess, and for both artists sculpture exceeds sculpture—through associations with computer-assisted production, the studio, gallery architecture, and imagined landscape. With Kilcollin, the excess also includes two seeming paintings. White resin blobs do the job of gestural abstraction, interrupted by the wall itself. Give them time, though, and they turn into views of vacant rooms with furniture in disarray. Are they banquet halls, conference rooms, or another gallery altogether? Again, you are either too early or too late.

A prayer for things

Actually, Annette Lemieux calls her installation Things to Walk Away With, but that cannot quite be right either. She may not be leaving them behind, at least in memory, but she has converted them into a meeting place and a work of art. She arranges them on the floor in a darkened room, in the outline of Chartres cathedral, as if to associate her entire life with western civilization and a place to pray. It is not, though, a scale model, like the model New York left over from the 1964 World's Fair at the future Queens Museum. She orders them solely by height, the tallest behind the missing altar, and none is all that tall. The ones near the front are almost comic in their flatness, as if after a fall.

Who knew that the Pictures generation had its pack rat? Richard Prince has his Borscht belt jokes and Sherrie Levine her appropriations, but they assault culture with a savage glee. Somewhat apart from the movement, Zito has his lawn jockey and Sophie Calle her confessions, but Lemieux is not angry or laughing, and she betrays no signs of love. She comes closer to Laurie Simmons with her dolls, but more in a spirit of reflection than of feminism or of childhood pleasures. A single object recalls Lemieux's past work, Nazi helmets dappled with polka dots, but this helmet belonged to a GI, and its peace symbol has all but peeled away. A baton lies inert and alone, as if she can no longer conduct her own symphony.

The installation goes well with "Altered Appearances," further selections from the Emily Fisher Landau Center upstairs. Any private museum resembles a cathedral to oneself and one's money, with all the nastiness of the art market that this entails. And this collection has all the chill of art after the 1980s, from Ed Ruscha to Matthew Barney—but with an admirable insistence on women, such as Shirin Neshat, Jenny Holzer, Barbara Ess, and Lemieux herself. A photo of a barely recognizable object, by Michal Rovner, connects to the gap between art and life downstairs. Photos of ghostly cities, by Vera Lutter and James Casebere, connect to Lemieux's model city shorn of a sense of place or of life. Other works of hers, sharing the first floor, round out a career.

Some suggest a fear of history, politics, and collective action, like the Nazi helmets. In Black Mass, frames containing only black obscure the message of a Chinese march in black and white. A lithograph of U.S. troops, divided by a central vertical into mirror images, bears the text Take Your Country Back Forward. A red canvas, Vital Organ painted up one side and down the other, or Sleep Interrupted, latex of a woman shrinking under the scrutiny of an actual light fixture, makes that fear personal. A text painting has no obvious speaker but a chillingly logical progression. Lines like these fall between puzzlement, vulnerability, and accusation:

Where are you

Where is she

Who are you

What are you

What are they

Why are we

One can try to locate Lemieux's felt needs in what an earlier survey called "The Strange Life of Objects." They may include past styles, like a glass inkwell or Italian ashtray. They may include an understanding of the past, like two family trees. They may include nostalgia, in a piano roll or child's clothes hanger, or escape, as from two worn but imposing paddles. What once held sway or brought comfort now looks pathetic, but it asks for a recognition of others. I cannot join her prayer to things or to herself, but I can allow her never to walk away.

Joseph Zito ran at Lennon, Weinberg through September 26, 2015, Dwyer Kilcollin at American Contemporary through March 15, Matthew Darbyshire at Lisa Cooley through March 29, and Analia Saban at Tanya Bonakdar through March 21. Annette Lemieux and "Altered Appearances" ran at the Emily Fisher Landau Center through January 4, 2016.