Two Nations

John Haberin New York City

Walker Evans: American Photographs

Bill Brandt

For the Museum of Modern Art, Walker Evans created uniquely American photographs, and others would surely agree. Not every photographer is so closely associated with a nation. Bill Brandt was, but was the quintessential British photographer a German? Perhaps, but he left a picture of England that endures to this day.

Maybe Brandt went in search of a nation out of a desire to belong, and maybe he reflects the perspective of an outsider all his life. Still, as the observer of place and class, he helped to create a nation's new self-image. And goodness knows, it needed one. Prewar England and Europe were becoming more and more a thing of the past. As the observer of naked body parts, Brandt also pushed the borders of photography. In the new cultural climate, who knows who might be looking?

Evans, for one, was always looking. That is as clear now as it was in 2000, for a museum retrospective. No wonder one remembers him for his studio. No wonder, too, that twentieth-century America's greatest photographer had to travel America to find it. Well, maybe not his studio, as I shall explain. Maybe, he might have insisted, ours.

In the studio

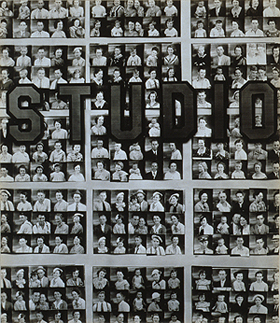

Sure, Walker Evans had a studio, but he was too busy documenting the Great Depression to stay home, and welcoming fashionable sitters was hardly his style. He photographed torn movie posters rather than film stars. He collected postcards, and he worked with MoMA to distribute a series of his own. He did not even care all that much for the darkroom, much like Marc Riboud then in Asia, not when others could handle the prints. Yet anyone will recognize at least one image in "Walker Evans: American Photographs," of more than two hundred faces from 1936. They form a tight grid in fifteen blocks of fifteen apiece, much like contact prints, crossed by the big block letters of STUDIO.

Of course, the studio was a photo booth, just as for Jared Bark many years later, where the penny pictures were taken one by one for each sitter alone—and maybe also for the Motor Vehicles Bureau or a date. With his clumsy large-format camera, Evans also photographed an actual booth from the outside, in the forbidding shape of a tall, dark wood shed. Here, though, he focused solely on the business sign and the people, and it could easily sum up his work. For starters, it is sophisticated enough, as photography about photography, fine art about popular art, and image become text. The grid, its flatness, and the repetition of signs connect it to Modernism before it, Pop Art to come, and maybe even its appropriation long after by Sherrie Levine (and then Martí Cormand). For just six months, MoMA places the display in its permanent collection of postwar art, on the way from Abstract Expressionism to Jasper Johns, with Andy Warhol soon to come.

And then there is the real subject, not in the studio but in America. These are iconic images, but this is not an iconic America. It is not the ideal of a single America. Nor, though, is it one America among many, the social history of a single time and a place. Rather, it is both multiple and anonymous, male and female, working clothes and Sunday best. Anyone who has a penny to spare can have a stake, although most of the faces are white—and no one, not even whoever ran the photo booth as a business, has a name.

Evans contains multitudes, and so does his vision of the 1930s. The exhibition marks the seventy-fifth anniversary of a show of the same name, which had one hundred prints and a catalog essay by Lincoln Kirstein. It is hard to remember, but the Modern did not even have a photography department back then. John Szarkowski, who became the museum's arbiter of the medium, was then only twelve years old. MoMA billed the exhibition as its first solo photography exhibition, although Kirstein had in fact displayed thirty-nine photographs by Evans five years earlier, to describe an American architecture. Evans had taken up photography only in 1928.

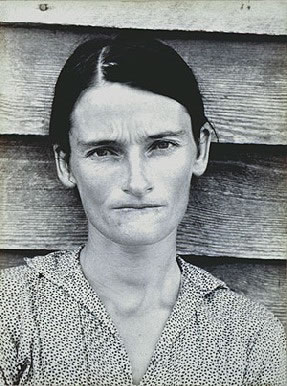

MoMA's recreation has more than half the original work from the fall of 1938—because the museum, remarkably, acquired that many for its permanent collection. Evans himself, working with Kirstein and the museum's publications manager, agonized over the selection. That penny studio sign has become a history of America and modern photography alike, because it opens the floodgates to memory. So does a rural main street, an automobile graveyard in Pennsylvania, a couple in a car with its top down but hardly on the open road, or an American Legionnaire hiding his frown and his insecurity behind a small mustache and his uniform. Many will recognize the simple box and steeple of an African American church, a sleeping child indistinguishable from a corpse, or a tenant farmer, her harsh cheekbones set against the wall of her home. All three are from the photographer's travels on commission for the Farm Security Administration and Fortune magazine, the travels that led to home country for William Christenberry in Alabama to and Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, with text by James Agee.

These are harsher images than one may remember—"slaved and ordered," Agee wrote, "for a crimesoaked world." They are never cruel, Evans seems to say, but simply necessary. Kirstein, a polymath best known for his collaborations with George Balanchine and their founding of the New York City Ballet, compared him to a family physician. He knew, though, that kindness can carry the patient only so far. Same goes for nostalgia today, looking back on a decade of poverty, racism, the rise of Hitler in Europe, and Surrealism in art. Kirstein praised the photos for "their clear, hideous and beautiful detail, their open insanity and pitiful grandeur."

"Overwhelming numbers"

Looking at the studio sign, one may miss the insanity, the pity, or the grandeur. The details can quickly blend together. The clarity of vision is there all the same, though, and it extends to the entire show. With the photographs of torn posters, one sees the populism and sophistication. With the individuals set against a shallow backdrop, one sees the empathy and the insistence on the moment. Most of all, one sees the multitudes.

Evans does not seek a mythic America, not even the disquieting myth in Edward Hopper and Hopper's New York. Nor is this the alienated America of American Surrealism or Diane Arbus. It aims to be neither comprehensive, as with Robert Frank, or, as with Lee Friedlander or Mark Steinmetz, just passing through. Neither is it a politically correct portrait of endurance, despair, and identity, as with LaToya Ruby Frazier. And again it is not just journalism, although a title like Penny Picture Display, Savannah, Georgia is quite specific enough. The New Deal and Fortune got what they wanted and more.

From the start, "American Photographs" claims little more than the plural. It groups the prints not by time, place, or series, but by subject matter—such as streets, buildings, and people. And then it mixes things up. The Southern farmer's wife hangs above a black woman in the shadow of the elevated subway. She could be in Harlem today, although this was Times Square. One would hardly know anyway, because once again names are not so easy to come by.

From the start, "American Photographs" claims little more than the plural. It groups the prints not by time, place, or series, but by subject matter—such as streets, buildings, and people. And then it mixes things up. The Southern farmer's wife hangs above a black woman in the shadow of the elevated subway. She could be in Harlem today, although this was Times Square. One would hardly know anyway, because once again names are not so easy to come by.

The museum supplies wall text, but as background on the photographer and the original exhibition. To learn the titles, one has to take a laminated card, if any are left, on the way in. The catalog adopts a similar strategy. It gives each print the dignity of a right-hand page, but then it groups the titles further back. A second edition had moved the titles to the facing page, but now the curator, Sarah Meister, moves them back. The blank verso seems to withhold a story of its own.

Many Americans look back on those days with wonder. Conservatives see a moral community of beliefs, liberals a moral community that looked both within and to government for hope and for a New Deal. Evans insists on the importance of community. He pursues it from rural Alabama to steel country near Bethlehem to the quiet of New England. He also invokes the impossibility of achieving it, beyond the community of the unemployed. Long before Alfred Gescheidt, Evans took a hand-held camera to the subways to find people neither alone nor together, much like now.

The show's placement on the floor for postwar art is an anachronism, but also revealing. As Kirstein says, the photos are not about unity or diversity so much as the accumulation of differences. "The power of Evans's work lies in the fact that he so details the effect of circumstances on familiar specimens that the single face, the single house, the single street strikes with the strength of overwhelming numbers, the terrible cumulative force of thousands of faces, houses, and streets." A Walker Evans retrospective at the Met in 2000 showed the extent of that force. Here one can see it crossing over into postwar America and slouching toward today. Take your selfie, upload it, and then ask if someone out there today still cares.

Their finest hour

Bill Brandt photographed a nation of high manners and low comedy, of literature and landscapes, of shadows and endurance. One can see it in the titles of the books that made his name, A Night in London and The English at Home. One can see it in the faces, beneath bowler hats and a parlormaid's lace cap. One can recognize the customs and the settings, from cricket to Billingsgate. He had few commissions but the freedom to do what he wanted, including nudes and stormy, sharply angled landscapes crossed by storm clouds and gulls. His career encompassed dark undercurrents and a variety of camera formats, but most definitely England.

Brandt's men and women from the 1930s stand apart from their background, but rarely apart from one another. They appear as spectators, at the races or at a bar, connected by anonymity and by craning more than a wee bit too far. They appear as workers, in the back stairs or in a window, connected by longing and heavy shadows. When a white figure stands alone in the light, in an evening in Kew Gardens, it is most likely an artificial bird. The people are less portraits than characters themselves. They play out a cross between Upstairs Downstairs or Downtown Abbey and Surrealism.

The real portrait was of England in the Depression, and it took Brandt well north to mining country to find it. On his return in the 1940s, London under the blitz had darkened as well, but he had little interest in overt damage, whether to buildings or psyches. His subjects still seek refuge in a stylized comedy, with the photographer ambiguously a part of the action and a stranger looking on. He also started a more notorious series in 1945, published in 1961 as Perspective of Nudes. Crossed hands give the appearance of buttocks right out of Pierre Molinier. Female body parts approach abstraction.

Maybe they and their brighter contrasts came as a relief after poverty and wartime, and maybe, too, they came with success. When Brandt finally takes up studio photography, including work for The New York Times and Vogue, he turns to artistry rather than brooding. He shoots artists with roots in Surrealism, like Max Ernst and Louise Nevelson, but also an artist as quintessentially English as Henry Moore. He keeps working almost to his death in 1983, with writers like Tom Stoppard and Martin Amis, but with time for the mods of the 1960s along the way. At the end, sitters become only their eyes. Presumably they and the photographer were watching all along.

For all that, Hermann Wilhelm Brandt was born in Hamburg, to a wealthy family in 1904. He joined a younger brother in Vienna in 1927, for the promise of a psychoanalytic cure to tuberculosis. His travels also took him to Paris and Man Ray, as an informal studio assistant, but he was not much inclined to talk about that either. "Nothing has ever happened to me," he insisted. "I think it would be less conventional and much more interesting to concentrate on photography and leave my life alone." The curator, Sarah Hermanson Meister, captures both the spirit of that statement and what it omits when she calls the retrospective "Shadow and Light."

One can look to Brandt's work for what he hid. Then again, he had plenty of influences and fellow travelers. His documentary of the 1930s has a parallel in Walker Evans. Its bare streets parallel Eugène Atget, its elegance Henri Cartier-Bresson and The Decisive Moment, and its unflinching strangeness Weegee. His early title all but quotes the 1933 Paris de Nuit ("Paris at Night") by Brassaï, someone else whose adopted name was a placeholder for a European identity that was harder to swallow or to pronounce. Call it conflict, assimilation, or art, but Brandt saw England's finest hour—in ways that Winston Churchill never dreamed.

"Walker Evans: American Photographs" ran at The Museum of Modern Art through January 26, 2014, Bill Brandt through August 12, 2013. A related review looks at a Walker Evans retrospective at the Met in 2000.