Three Friends

John Haberin New York City

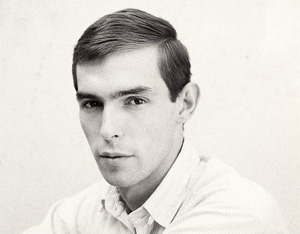

Peter Hujar, Paul Thek, and David Wojnarowicz

One could imagine friends just having fun together—or just one man trying on roles. In close-up he is louring, pouting, smoking, weary, or downright clean-cut. He lies aimlessly, on the floor or in the woods. He dances naked and breaks the surf at Fire Island. One under the drill, eyes as wide open as his mouth, might be staging the Nazi dentist scene from Marathon Man as a put-on. But no, it is Peter Hujar, with "Three Lives" rushing by like a slide show or a lost afternoon, and never mind that all three men are now dead.

His photographs show himself, Paul Thek, and David Wojnarowicz—perhaps three of the most self-conscious artists ever. An immense, almost still image of Thek dominates Thek's Whitney retrospective of just a few months before. It seems only fitting, for he looks young, impassive, and vulnerable, even at the top of his fame in 1964. Wojnarowicz, whose video became the controversial centerpiece of gay portraiture in Washington, had his own retrospective more than a decade earlier. Together, they flesh out Hujar's three lives. And there is more to their lives than what Julia Kristeva, the philosopher and psychoanalyst, called abjection.

For Wojnarowicz, allegory can short-circuit meaning. He risks not always knowing which impulses he has chosen and when he has merely accepted. He depends on prior texts, but that means repeating cheap stereotypes and received images. He came up in the heat of East Village art, and ironically its hot gallery years were few. Surviving dealers moved to Soho as fast as gentrification and opportunism could carry them. At the New Museum back in 1999, one looked back at the impasse of the 1980s, with the chance to puzzle freshly over the blockages and joys of art today.

He led three lives

Roles for Peter Hujar pass as quickly but only as quickly as three short lives. The thirty photos span about as many years, almost up to Hujar's death in 1987 at fifty-three. They show himself and two lovers, Paul Thek and David Wojnarowicz, and they show the passing of time. The relatively clean-cut self-portrait dates from the 1950s, when people looked like that, if maybe a little less cold-blooded. The increasingly gaunt, dark, and grizzled faces might serve as a record of AIDS. The actual dental visit might serve as a metaphor for it.

Frankness here is never far from attitude. Thek seems most emotional but also most theatrical, in the woods or in the waves. This is, after all, the artist who sculpted the illusion of raw meat. Wojnarowicz seems most beaten down, and his most notorious video centers on an image of the crucified Christ. Hujar stands furthest from his own camera, even in the nude. The flashbulb both highlights and hides his crotch.

Sex remains just off-camera, much as for Alvin Baltrop—metaphorically, as with Wojnarowicz holding a snake, or literally so, with a masturbating Thek only halfway in the frame. So does companionship. Wojnarowicz entered the other men's lives only in 1980, and they never share a photo. While Hujar and Wojnarowicz both pose as "Cindy," they have in common mostly immobility and a telephone. Not that either of them speaks. If he did, Hujar could have said, "I led three lives."

One knows him best through others, like such subjects as Candy Darling and Susan Sontag. He fills a hole, no doubt, in a narrative about East Village art, art in 1993, the gay community, or AIDS. He also fills a hole in weirdness and in time between Diane Arbus and the self-involvement of Nan Goldin or Sam Taylor-Wood. Hujar's work in Mexico shocked Wojnarowicz into that notorious video, A Fire in My Belly. His retrospective a few years back skipped New York City, but this will help.

For a photographer like Goldin, early Diane Arbus, or Catherine Opie, gender means posing and dressing up. Even halfway nude, perhaps with piercings, Opie's surfers and bikers are playing a role. Hujar's subjects are dressing down. Sontag lies on her back in a sweater, and one feels relaxed in her company. In different ways, Opie's confrontations and his playfulness are tokens of frankness. He makes one at home with three lives and three deaths.

Speaking of Nan Goldin, Hujar's dealer gives her and her friends its other space to carry on in the present, both as photos and as Scopophilia, a slide show. They have plenty of attitude, too—enough to appropriate a history of Western art. They pose handsomely, inspiring pairings with all sorts of quote-unquote masterpieces, but with a notable fondness for the drama of Renaissance Venice and the Baroque. One wants to credit them with debunking art history, perhaps as a male endeavor with erotic subjects. In practice, they revel in it, like Marcel Broodthaers and his ultimate "imaginary museum." Yet I can still imagine a museum all their own for just three friends.

Remains of remains

Paul Thek pictured himself again and again as a diver, suggesting both daring and surrender. It may also allude to Diver, by Jasper Johns—which, in turn, may allude to another gay male death in Frank O'Hara. Thek seems to have sought death in his entire career. One remembers him most at age thirty-one, for that first series of body parts in glass cases. It only adds to the apparent decay of those monstrous limbs, that garish torso, that pale mask, and those dangerously convincing hunks of beef that the wax has proved an art restorer's nightmare. His largest show shattered in pieces on its way to Europe, and his single largest work cast from his own body hardly survives at all.

It makes sense, too, that one may ever see again so large a projection of a Warhol Screen Test as in his museum retrospective. Thek's illusions pick up Warhol's mix of pop culture and morbid philosophical puzzles—not to mention a side of beef by Chaim Soutine, soft sculpture by Claes Oldenburg, the dark self-exposure of Eva Hesse, Bay Area creepiness, or the sweet temptations of Wayne Thiebaud in Thiebaud drawings. When he sculpts onions or shells, they sprout and grow as well as decay, much like sculpture for Liz Larner. I could see the Young British Artists as Warhol retreads, but I had never thought to ask just how one gets from late Warhol to Damien Hirst. Once Thek even places his dark slab in a Brillo box. Perhaps someone else will place a Brillo box in a shark tank.

Thek has become as much an exemplary figure as an artist. In fact, "Paul Thek: Diver" has earned rave reviews that hardly mention the work rather than the life. He was the bisexual with a Catholic upbringing who died of AIDS, like Mapplethorpe, and the self-imposed exile in Europe who could not keep away from the United States. He was the lover of Peter Hujar, the photographer, and the dedicatee of Susan Sontag's Against Interpretation—and he returned the favor with an offer to bear her child and a painting bearing the words Susan Lecturing on Neitzsche. Sontag did not often misspell writers or philosophers, but her theory demands raw experience rather than theory, much like his art. He was an outsider within, just in time for modern and postmodern narratives alike to fall from favor.

There is not much work to be seen anyway. The Whitney struggles to fill a floor, even with the dull paintings that occupied him from the mid-1970s to his death in 1988. From the very first, though, he is in search of an identity and not able to fill it—which makes him an exemplary postmodern, too. His bronze alter egos include Tar Baby, the Pied Piper, oversized garden gnomes, and those recurring body casts called Fishman. He starts with peculiar Head Boxes, or chairs placed over his head like a sadomasochistic harness. When they shatter on the way to Europe, he settles for what he gets, and I suppose others will have to as well. He keeps searching for rituals, in the bronze tools and burnt-out campfire on a rug.

Like Hirst or Charles LeDray, Thek plainly has a taste for moral fables, even if he is uncertain of the moral. He writes I shall have a sense of humor at all times over and over, like John Baldessari without the sense of humor. He places tiny chairs up close in front of those last paintings, when he is already dying. He will be a good little boy, they seem to say—and so will you, sitting up straight and paying attention while there is still time. A quote on the entrance wall repeats other lessons:

Design something to sell on the street corner

Design something to sell to the government

Design something to put on an altar

Design something to put over a child's bed

Design something to put over your head when you make love

Remember the joyful advice of Jasper Johns—to take an object, do something to it, and do something else to it? Thek is bridging again from Modernism, but with a postmodern uncertainty. If he survives, it will be as that exemplary moment, along with the Brillo box and the one large body cast more or less still in existence. Fisherman in Excelsis from 1971 ropes him to a table that descends from the ceiling, like the title figure in Angels in America twenty years later. It also leaves him in strict restraint and in decay. It is the remains of the artist's remains.

Anger, bluntness, and repetition

David Wojnarowicz's cartoon allegories pile up and recombine in work after work. They take their force from their familiarity as much as from a particular context. More often than not, they float above an image of the artist's sleeping head. While his one lasting work led to repeated denunciations over the years from the religious right, one can see it all as his worst nightmare. The video, A Fire in My Belly, wraps the obsessions of all his art in one unruly package, and I give more space to it in a related review. His images argue that a gay man can never altogether choose his fate, but they release the uncontrollable power of an artist's dreams.

The New Museum finds its strength and weakness in its partisanship. It is a champion of the marginal, which it defines in opposition to tradition. Instead of the white, male, and heterosexual, it speaks for the outsider. Instead of a modernist tradition from representational art to abstraction, it presents blunt speech, from folk-art styles to media-influenced montage. That can lead to hectoring or, conversely, a shallow trendiness. Yet the museum is determined to undo silence, and with David Wojnarowicz it succeeds.

The New Museum finds its strength and weakness in its partisanship. It is a champion of the marginal, which it defines in opposition to tradition. Instead of the white, male, and heterosexual, it speaks for the outsider. Instead of a modernist tradition from representational art to abstraction, it presents blunt speech, from folk-art styles to media-influenced montage. That can lead to hectoring or, conversely, a shallow trendiness. Yet the museum is determined to undo silence, and with David Wojnarowicz it succeeds.

In a nasty photograph related to the video, thick threads again sew up the artist's mouth, and a needle points right at the center of his bloody face. Silence could well lead to death. In the video itself, newspapers linger over violence, as if to preclude silence or to remember when new media were not even necessary. No wonder that Wojnarowicz gets to speak in so many media. His retrospective slouches across three floors like a house party. Paul Thek never got as much mileage out of that same imagery, and he did not masturbate on camera either.

Everything in Wojnarowicz goes over the top, and everything asks for forgiveness for the pain of others. His repeated motifs testify to his tense mix of playfulness and anger. Their numbing repetitiveness comes from his allowing both to settle into abstractions. They seem at times aimed straight for mass culture after all, and Saks Fifth Avenue used his motifs for store windows the same winter, in honor of his show. Had his video, with its image of ants crawling over a crucifix, offended the Catholic League? After his death, he became virtually a Christmas display.

Perhaps he used the same needle and thread to prepare a turkey for his cruelest video. He shows the ideal American family sitting down to Thanksgiving dinner. But the turkey is smeared with blood, and the family is mired in self-hatred and mutual rejection. The artist knows just how brutal the rejection could become. Yet by poking fun at an easy stereotype, the artist recovers it for others. It does the same with the cartoon imagery of painting after painting.

The sewn-up mouth has a double or triple meaning that Wojnarowicz may never have intended. I felt not just a gay man's forced silence, but his work's refusal to speak for anything but itself. At a crucial moment, it recapitulates a refusal of meaning, just when the artist wants most to find some kind of sense. It even begins with a refusal of closure of another sort—its very opening screen, "A Work in Progress." Naturally the video led to a second video, like outtakes but tighter. And naturally that opening title screen appears scrawled as if in blood.

Peter Hujar and Nan Goldin ran at Matthew Marks through December 23, 2011, "Paul Thek: Diver" at The Whitney Museum of American Art through January 9. "Fever: The Art of David Wojnarowicz" ran at The New Museum of Contemporary Art through June 20, 1999, with additional work in the Saks Fifth Avenue windows through February 2. A related review concentrates on Wojnarowicz's video and "Hide/Seek" at the Brooklyn Museum through February 12, 2012. I am grateful to Stephen Koch, director of the Peter Hujar Archive, for two corrections and for direction to a forthcoming biography of Wojnarowicz by C. Carr. It is unclear whether Hujar's diagnosis with AIDS predates, and thus could have affected, that video. Related reviews take up both Hujar and Wojnarowicz in retrospective.