For Goodness Sake: I

John Haberin New York City

John Carey: What Good Are the Arts?

It sounds too good to be true. For once, a book about art will not add yet another diatribe against the present. The author says so himself, just in case I missed the point. He has survived way too much shock at the Turner Prize, and he wants none of it. Or does he?

Tolerance—to a point

What Good Are the Arts? It may sound like a self-help guide or a taunt. If you know that John Carey hails from England, where the academies and East London alike present art as a kind of stern lecture, you may have guessed that he is getting confrontational. And you would have guessed right. The arts, Carey argues, does the world no good at all—especially fine art. In fact, he would much rather settle down with a good book.

He does throw the arts a bone, however, even if he does his best to scrape off the meat. Not only are they not good for you, but you have no right to complain. Does it seem these days that one can pass off anything as art? He sees no reason at all why not, and he imagines an art world open to as many styles, tastes, needs, and even definitions of art as there are viewers.

Which, then, carries the day—the vices of art or the virtues of an art-world democracy? Unfortunately, disentangling Carey's ripostes from his open-mindedness leaves only a sweeping, sloppy polemic. It does, however, help in disentangling some slippery questions of definitions and what they portend for understanding.

Carey thinks that it makes no sense to ask others why they call something art. He does not ask what claims a work makes on one's own values or why philosophers who think otherwise have gone astray. When it comes to art, however, if you not have to ask, you cannot afford it.

I shall begin with his claim to open-mindedness. I shall argue that he uses the point, ironically, as a weapon to beat up on a more liberal view of the arts, one able to embrace any number of styles, forms, and media. Only that view, moreover, can cope with art now and its growing public. In particular, I shall question his support in the end for a narrow view of the arts, one with room for little more than English poetry. I shall argue that he cannot at once dismiss the search for value judgments in the art while clinging to a conservative picture of degenerate art.

In the second part of this essay, I shall bring the argument back to what can or cannot define one art from another or art from real life. I shall argue that abandoning the distinction takes guts, but it also takes giving up on tired ideals of art or real life. Rather, I shall claim that every judgment about art challenges the judgments of others as well. It means seeing something as art. Last, one should not see that as a definition of art, but rather as a challenge to what one sees as life.

Up to no good

Sick of hearing that any trash and any provocation counts as art, like a thrift-shop Jackson Pollock? Well, says Carey, it does count—and fine with him. If you want to call something art, perhaps even this Web site, you go right ahead. You do not have to call yourself an artist to make something art. Cary's imaginary gallery has room enough for insider deals and outsider art, hot trends and lonely holdouts.

Complaints about declining standards, like those of Jed Perl, often takes another form, as a defense of "slow art" against popular forms. As a third alternative, it may involve a defense of the proper function of art. True art, this line goes, improves the soul, or at least it offers an education in what and how to think. And here, too, Carey is eager to move on. He calls his book What Good Are the Arts? You can guess his answer without so much as reading the jacket copy—absolutely nothing.

I want to love this book. As an American, I can substitute any number of political storms for Carey's British experience. This site has defended public art funding against Jesse Helms. It has explored the cheap outrage at shock art and the motives behind censorship. Feel torn between conservative holdouts and cutting-edge philosophers? Like Carey, I have trouble allowing either to define art.

Carey's assault on good taste resonates with a great deal of contemporary criticism as well. As someone who takes his medicine only on doctor's orders, I want again to applaud. Once the province of modernists like Clement Greenberg, the battle of art versus kitsch has now become a conservative lost cause. In Greenberg's day, perhaps, the champions of progressive art cited Marx and Jung. Nowadays, Greenberg's ideal of geometric abstraction survives, but as one among many styles and media, while its unique virtue has its staunchest defender in a right-wing broadsheet, The New York Sun. Rudolf Stingel even combines formalism, Minimalism, confession, and kitsch in the same tawdry installation.

Connoisseurship, too, has returned more to its associations with privilege. Skeptical critics are seeing older classifications between genres and forms as acts of exclusion. When these critics say that anything goes, they mean to rescue from oblivion B movies, humble crafts, and the men and indeed women who made them. New art histories, too, are asking exactly who excluded whom, when, and where. Such critical histories have traced common assumptions about art to its display in museum institutions and commercial settings.

Unfortunately, the book sounds too good to be true for a reason: it is too good to be true. Carey may rescue esthetic judgment for all, but he just so happens to dislike art and discourage reasoned judgment. He may stick up for ordinary experience instead, but he also despises most ordinary tastes. Clearly something has gone wrong, but what?

Putting in a good word

For the most obvious sign that Carey has gone off the rails, consider where he ends up. In the book's last and longest section, the English critic tries to prove the superiority of literature to the visual arts. It sounds implausible. If Hitler began as a painter and loved Wagner, the Nazis also had a Shakespeare society. What kind of contortions, then, allow Carey to justify it?

For starters, it contradicts everything that has come before. Cary distances himself from rabid denunciations of the arts, but now he adds his own. He affirms that nothing distinguishes a work of art from what Arthur C. Danto calls ordinary things, but now he has no trouble defining art and literature. He sees no reason to prefer the fine arts to popular entertainment, but now he quotes poetry. He denies the arts moral, cognitive, or psychological benefits, but now he discovers those very features in books. A bit embarrassed himself, he notes in passing that he does not really mean that literature is good for you, only that it teaches you to think, and I know you feel grateful already for the lesson.

Even did he not contradict himself, he would make me wish to close the covers with a bang. Whenever criticism finds a consistent value in an entire art form, it is mining art for a predetermined, universal set of standards, meanings, and ways of seeing. Conversely, whenever criticism broadly dismisses art, it marks the critic as unable to find anything in it. Either way, the critic is unable to help others look. As I have asked about my own mixed reviews, why should you trust me when I miss the point—or why should I trust myself? No wonder that when critics of arts funding look at contemporary sculpture, they so often see nothing but straw men.

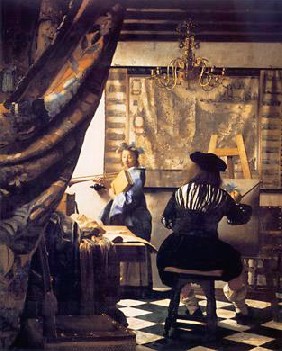

On the one hand, Carey argues, only literature can make one aware of its own limits, for only literature can speak precisely enough about itself. Because words have reasonably explicit meaning, writers can take their own style and insights as its very subject. He must have missed out on everything from Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror by Parmigianino or the Art of Painting by Jan Vermeer to Edouard Manet in his assaults on Titian and Diego Velàzquez or Still Life with Plaster Cast by Paul Cézanne. He has certainly missed the endless artifice and self-quotation in Pablo Picasso and the Henri Matisse of The Red Studio, not to mention the decades of appropriation art since Andy Warhol and Warhol's influence. He can hardly begin to encounter postmodernist criticism, which so often describes art as text—or the news as a constructed image. That use of text, itself a text and itself a metaphor, has a way of destabilizing meanings, and it might have made Carey look more carefully at the happy result of literary self-reflection.

On the other hand, he insists, only literature remains vague enough so that it will not shut down meanings once and for all. It makes one wonder why he found art too inexpressive a moment before. In fact, he glides over another common presumption about art and its distinction from words. The broader public loves art for its aura of silence. Artists themselves often resent criticism for trying to pin them down in words. I have argued with both stances, but Carey will not examine either one, because they cut too close to his literary ideal.

Carey wants to praise literature for both its precision and its reticence. He may have both right, but as sweeping generalizations rather than shifting points of light, they can only contradict one another. Only when one gets to the details of how prose works—not as message but through style, image, subject, and metaphor—can those contradictions take on complexity rather than incoherence. At that point, however, he would have to deal with art.

Degenerate Nazis

Carey, then, wants supporters of the arts to stop telling the public what it really needs, but he is not above a few directives himself. To see how he got himself into such a bind, it helps to work backward through his argument. Why not turn to art for insight, provocation, or even moral and intellectual improvement? In replying, Carey has history on his side—or does he?

Artists and their patrons have often put their ideals into practice, and not all these ideals can simultaneously hold true. They have include warring religions, nations, and politics, and they have ranged from transcendent beauty to the intrinsic value of everyday life. Moreover, while the growing secular, private conception of Western art has plenty of messages of its own, it has led many to insist on how little their work means. Think of voices as distinct as Oscar Wilde and Frank Stella. All art is quite useless. What you see is what you get.

Yet this history suggests that art always comes laden with values, and viewers inevitably find their own values at once reinforced, challenged, and put to the test. They may have to learn to look, and they may have to participate in community decisions about art's place and function. It does not sound like a bad start. Carey himself has found that a good start for literature. He even ends the chapter debunking art's educational value on a high note, conceding that making art gives convicts a better shot at a new life.

He gets around the problem just as he does in contrasting art and literature, with a passel of straw men and a heaping portion of disdain. Carey races through any number of traditional defenses of beauty or the psychology of art as patently lazy, false, contradictory, or elitist. That allows him never to dwell on any of these defenses on their own terms—as interpretations of art and experience, each with limited but potentially valid insights. He naturally plays the Hitler card. Not only did the man love certain art and music, but he saw them as part of a dangerous ideal of German national culture. Worse, Hitler began as a painter.

At this point, Carey gets hysterical. He leaps to the conclusion that Hitler killed millions because of painting. Perhaps he invented his own cultural and moral muddle that just happens to include mass murder, or perhaps he turned to mass murder because he had to give up painting. Still, many would agree with Carey had he only stopped with calling Hitler's exposure to art useless, so it helps to linger a little longer. The infamous example of Germany actually proves both far too little and far too much.

It proves too little, because it rests its case against the arts on a man who banned art and killed artists. Moreover, it relies on an artificial aggregate of wartime responses in the German population. No one can know who would have died without Wagner and who would emerged with sanity intact. It proves too much, because no one claims art as a definitive recourse against madness. One might as well ask to abolish education, much less art education, on the grounds that some kids fail math or grow up to become thieves, art critics, and reckless drivers. In the continuation of this essay, I shall see what that bizarre request might mean for the definition of art.

John Carey's What Good Are the Arts? was published in 2006 by Oxford University Press. This is the beginning of a two-part essay in review. The second part of this essay returns to definitions of art. Related articles on this site have considered the possibility of indiscernible works of art, the legacy of Arthur C. Danto, the possibility of purely conceptual art, claims for such traditional criteria of art as expression and beauty, the possibility of a single defining art world or art worlds, the necessity of judgment, and whether a fantastic installation in Central Park fit any definition of art at all.