On and Off the Street

John Haberin New York City

Mark Cohen and Barbara Crane

Alfred Eisenstaedt and Jared Bark

Mark Cohen and Barbara Crane offer alternative definitions of street photography—one rooted in the working class, the other in urban architecture. Both are out to capture the brutal reality of a changing community.

Something larger than life can have its moment, too, even on the street, thanks to Alfred Eisenstaedt before them. Still, the site of his most indelible photograph also held small and not quite private spaces. More than twenty years after Eisenstaedt, Jared Bark returns to Times Square to make dark use of a photo booth. The innocence is gone.

Working-class Surrealism

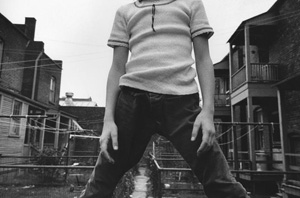

Working-class Pennsylvania was the place to be, and the children knew it. At least they pretended they did for Mark Cohen. A boy holds a cat confidently in one hand, its tail on his bare shoulder and its wide eyes very much in your face. Another bounces a ball too big and too good to be true, and girls hang happily upside down. Cohen lingers over bare legs, spread confidently below shorts, swimsuits, or skirts. He is not projecting his lust onto the underage, any more than Scott Alario with his daughter's longings, but watching as they discover a less-innocent world.

For all their pleasures, the inhabitants are tangled up in decrepit housing, unpaved streets, and their own desires. The tangles extend from twisted cables in an empty yard or strands of a wire fence left for trash to a jump rope halfway between a girl's legs. They are implicit in the unspoken record of a scrap of paper on mangy earth. They include the gorgeous strands of a young woman's hair, but also the narrative tangle of her face buried in her hands and a man's arm reaching out to touch her. Has she recoiled from the threat of violence or failed to register his support? Does either of them know?

Cohen had a solo show at MoMA in 1973, and he worked increasingly in color, at a time when art photography was not altogether accepting. The change took him more toward group shots, in search of tensions within entire families. Still, his color compositions are flat compared to the wildness of black and white. That bare-chested boy has the smile and sunlit hair of an androgynous god, with the black cat a Madonna's demonic child. Photos like this one update René Magritte and film noir for blue collar America and a decade of turmoil. From the look of things, they did not have far to go.

In 1976, Barbara Crane set out to take another city's portrait, one building at a time. True, she could not invite downtown Chicago into her studio, although Zoe Leonard comes as close as one can to bringing the Upper East Side into the 2014 Whitney Biennial, quite apart from her travels, with the museum architecture itself as her camera obscura. Crane could, though, take the care and equipment of studio photography outside, where for three years she took more than five hundred 5 by 7 negatives. Where once a Leica had brought to street photography the pulse of a city, she took the reverse route, accepting accident but not anecdote. Shadows, edges, and planes have a place, but little more. This is not about a preservationist's detail, but the rhythms of disorder.

Crane allows just one contact print to a gelatin silver sheet, its broad edges blackened in the process. The camera's film holder adds an additional slim border, which she did nothing to efface. Then she makes her selections, first to ninety, then to forty for a book, and now for the first New York solo exhibition of Chicago Loop. A city then was in transition between Modernism and its aftermath, much like art. One can see the grid of windows and of formalism, the textures of stone and glass, the diversity and decay. Landmarks are hard to come by, but one knows where one is all the same.

Born in 1928, Crane studied with Aaron Siskind at Chicago's Institute of Design, founded as the "new Bauhaus." Like the Bauhaus, she can appreciate design and architecture as a vocabulary for living subject to repetition and to change. And like Siskind, she approaches abstraction, with objects at rest and people close to a frenzy. She has photographed a single stick, a single mushroom, a single child, and hands and waists cut off as in a dance. For the Loop, a façade can line up parallel to the picture plane, but even corners in close-up define a shallow depth. With her head under the black cloth of a large-format camera, one can imagine her reminding a building to face the camera and to smile.

Larger than "Life"

Some photographers capture people as they are. Alfred Eisenstaedt captured people as they are in Life. He photographed Katherine Hepburn sprawling at ease and all the more glamorous for it. He photographed Alfred Einstein with a pencil in hand and a rumpled sweater, JFK leaning over headlines about a nation in his hands and in crisis,  a waiter on ice skates deftly raising one leg to avoid a table, and a fashion designer with the black lace pattern of a butterfly covering one eye. Ballerinas step up off the studio floor, onto a window sill, and into the light. They are playing a part, much like Cindy Sherman in denial of a fixed identity, but only because they are playing themselves.

a waiter on ice skates deftly raising one leg to avoid a table, and a fashion designer with the black lace pattern of a butterfly covering one eye. Ballerinas step up off the studio floor, onto a window sill, and into the light. They are playing a part, much like Cindy Sherman in denial of a fixed identity, but only because they are playing themselves.

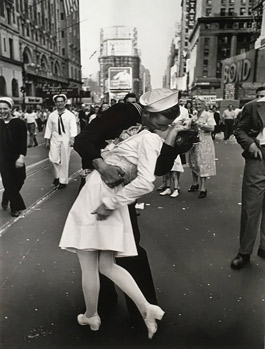

Maybe you are not old enough to remember Life magazine, a kind of picture perfect Time. You can hardly help, though, remembering at least one photo by Eisenstaedt, of a sailor kissing a woman in Times Square. She bends over backward, one foot raised on its toe, as he leans into her with all his might. He has, if not quite literally, swept her off her feet. Together, they swept a generation off their feet as well. In Eisenstaedt's hands, a humble sailor's uniform and a woman's white dress and shoes are larger than life, but never larger than Life.

Was Eisenstaedt the father of photojournalism? Born in 1898, he was almost ten years older than Henri Cartier-Bresson and five years older than Walker Evans. (He was younger than Dorothea Lange, but for people into embarrassing metaphors, that would make her its mother.) Life had pioneered its large format and devotion to photography even before Henry Luce, the owner of Time, bought it for his empire in 1936. And this photographer was a signal part of its golden age. Long before Jane Dickson settled there, he shot that moment in Times Square, the center of the world to an American in 1945, and he knew just what he wanted at its center.

He never came unannounced, and he never hid his camera like Walker Evans in the subway. He never had to rip away pretense like Don McCullin in wartime to reveal shame, vulnerability, or pain because they never once appear. He never had to seek the "decisive moment," for he could always make it so. Others have named alternatives like those as the very essence of photography—as ways to capture people, always people, unaware. Not Eisenstaedt. People here are always putting on a show for themselves, for the photographer, and for you.

Can you possibly imagine Eisenstaedt just happening to stumble on the kiss on the sly and rushing out his camera? Are two women behind the couple staring at them or at him? Here anyone can become a star, by blurring the line between actor and spectator. Children read with delight and gasp at an unseen puppet show, while a woman in an upper tier at the opera turns away from the performance. They all also belong to a larger moment in history. The kiss occurred on VJ Day, the ballerinas were the future of the American Ballet Theater, the opera was a premiere at La Scala, and the glory of the old Penn Station holds not commuters but a farewell to service men.

Eisenstaedt can seem to belong to commerce rather than art. Surely a proper photojournalism would face up to reality as he knew it, and a proper postmodern artist would create his own fiction. Richard Avedon belongs to both worlds, photographing Marilyn Monroe as a silent firm star. Eisenstaedt sees her only as her sexy desired self. He shows artistry all the same. His just happens to be artistry for the popular imagination.

Grainy memories

It could almost show the crucified Christ. The grainy assemblage by Jared Bark looks to have been around a long time—if maybe not that long. It closely crops a gaunt, bearded man stripped down to his black underpants, his hands clasped behind his head. It brings together four photographs, from his head to his knees, that never quite fit together, and it is hard to know what their varying tilt owes to the camera and what to its subject. It is hard to know, too, whether he is at rest or in agony. And then Bark doubles him, immediately to his right, with three more.

His keen stare and his redoubling add to his presence, while the doubling amounts to image manipulation—and so a mark of absence. Bark is feeling his pain, even as his dismemberment of the body adds to it. For all I know, the image is a self-portrait. Apart from its narrow dimensions, it could also be a contact sheet from a photographer who never got around to proper prints. Either way, it seems unspeakably private, except that it has found its way into the gallery. And the entire show unfolds in a curtained space both public and private, a photo booth, as "Public Private."

By the time of this picture, in 1975, Bark had bought his own photo booth, so that he or his subject could expose himself, give or take his private parts. He began, though, six years earlier in Times Square. Back then, with its porn shops and tawdry street life, it was a public space for private matters, too. Before her better known works, Diane Arbus photographed a nearby "museum" of the grotesque. But then the populism of dime-store portraiture appealed to Walker Evans and Ray Johnson as well. Bark has described a photo booth as a "marginal public/private space."

Not that he could no longer handle life on the margins, but he was getting restless. He could do only so much for a few pennies, in public or not. Entire assemblages seem restless, too, as slight variations on a single image ripple across. Bark brought magazines to Times Square (or bought them there) and photographed their pages, well before Sherry Levine, the photographers in "A Trillion Sunsets," and critical theory made "rephotography" a byword. They show a small animal, a turkey, and any number of body builders. Animal instincts, failure, and male sexuality are in the air.

In his studio, the second-hand photo booth became that much more of what the gallery calls a "theater and image-making device." There Bark could also photograph another device that functions as just that, a TV set. Its screens display ice hockey, the evening news, and whatever else matched his obsessions or chanced his way. He must have liked that sports and the news relay breaking events, in the present, while the groomed talking heads would fade further and further into the past. He must have liked as well that photographing a TV screen intensifies the grain. He rubs it in by squeezing more and more images into a sheet.

The gallery's main space brings back Laura Letinsky, with obsessions and rephotography of her own. Last time out, I could note how she draws on Cubism, Surrealism, and commercial photography for portraits of art and desire. Now the images, casually taped to the wall or tossed on the floor, bring out the fragmentation of the studio all the more. They have that in common with another gallery artist, Paul Mpagi Sepuya—a gay photographer who shares Bark's concern for male bodies. Now, too, the bare whiteness of Letinsky's studio looks all the icier after Bark's dark grain, but then he has entered the grainy space of memory as well. Before his debut here, he last showed in Manhattan in 1979.

Mark Cohen ran at Danziger through June 20, 2014, Barbara Crane at Higher Pictures through June 21. Alfred Eisenstaedt ran at Robert Mann through April 27, 2019, Jared Bark at Yancey Richardson through October 19.