Photography Objects

John Haberin New York City

Studio Photography and The Photographic Object

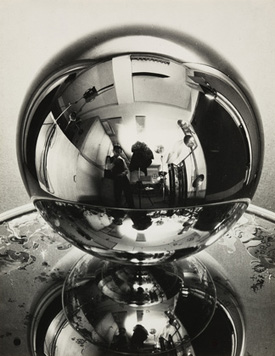

When May Ray photographed his studio in 1935 as reflected in a silvery orb, he called it Laboratory of the Future. Five years later, when the Museum of Modern Art created a photography department, it might well have adopted the same title. It had much the same idea in mind, and its impact in shaping a canon for decades to come was every bit as great as in painting and sculpture.

So when a new chief curator rehangs all six rooms for photography, one expects revelations. Where is photography going, and how about MoMA? Maybe nowhere fast, but for now they are heading indoors. "A World of Its Own: Photographic Practices in the Studio" will have anyone looking for clues to MoMA's future.  Its very theme rules out much of what one takes for granted today. Has the canon shifted once again—or simply lost its meaning?

Its very theme rules out much of what one takes for granted today. Has the canon shifted once again—or simply lost its meaning?

Whatever happened to photography anyway? Not that it ever went away. No, it went viral, slipping into everyone's hands and onto the Internet. It passed more easily into fiction, now that one no longer needs printing and double exposures to "enhance" it. It entered painting and sculpture, once chemistry and collage could bring its smoke and mirrors to abstraction. Somehow, in a digital age, it became an object.

Of course, it also began as one, in and out of the studio. Early photos, too, served as constant companions and remembrances, in lockets, where they largely took over from painting the role of portrait miniatures. A cell phone's images may seem disembodied, but they function much the way. Before you blame that couple posing between in front of you in the museum, though, it has happened before. "The Photographic Object" recreates a 1970 exhibition at MoMA curated by Peter Bunnell, give or take creative substitutions. Coming largely from the West Coast, the exhibition managed to subvert both Minimalism and Pop Art.

Photography looks within

At MoMA, out goes portraiture of famous artists in their galleries and studios, the kind of history just recently in the museum's "American Modern." Out goes an actual penny studio, the photo booth that Walker Evans turned into an image of America. Out goes the studio's traditional role as a commercial portrait studio, although the show includes Irving Penn, Richard Avedon, Julia Margaret Cameron, and Robert Mapplethorpe. For that, one would have to detour a mile to the Whitney, to see Edward Steichen at work for Condé Nast. Above all, out goes photography's incessant search for America, from its politics and seaminess for Garry Winogrand and Diane Arbus to its small towns, gas stations, backyards, and open roads for Evans, Ed Ruscha, Joel Sternfeld, Robert Adams, and Lee Friedlander. Even the maker of The Americans, Robert Frank, turns up through Polaroids of his Boston studio.

The show may also leave trail hunters disappointed. This is still the storied permanent collection, not a repeat of MoMA's fall 2013 display of "New Photography." It sticks almost exclusively to black and white, although Jan Groover in still life and Walead Beshty in large, near-abstract photograms offer stunning bursts of color, like those of Sam Falls elsewhere. Critics have found the entirety dated, repetitive, and even "demure"—but then a cynic might say the same about Modernism. In conversation, Quentin Bajac, the curator with Lucy Gallun, disclaims any grand agenda. He has only a show in mind.

It is an ambitious show all the same, as well as a slippery one. It allows a medium its own world, much like formalism, and its ninety artists and nearly two hundred works defy a quick summary. It gives each room its own theme as well, for the studio as stage, as set, as playground, as backdrop, as laboratory, and as workplace. And which, it asks implicitly, is the studio itself? In practice, the themes can seem slippery as well. By laboratory, it has in mind experiments like photograms and strobes, while Man Ray's Laboratory is in the room with a photographer's day-to-day environment.

Not that the groupings are meaningless. From Man Ray, one can turn to Bruce Nauman with his studio as waste site or Uta Barth's over the course of a day, saturated in light. One can watch Geta Brǎtescu scouring her studio in Bucharest, as if in search of herself. One can see Josef Sudek approach his studio both from without, across trees and snow, and from within, looking out at the same but now distant scene. In their playground, one can see Adrian Piper nude but in darkness, Bruce Nauman playing catch with himself, William Wegman with his dog, or Peter Fischli and David Weiss with their self-destroying perpetual motion machine. Among stop-action experiments, one can compare Harold Edgerton and Eadweard Muybridge half a century apart.

The groupings are meaningful, too, by what they leave out. Two artists, known for photographing small models as if they were grand haunted spaces, still deconstruct the play between artifice and realism. Yet here James Casebere works in small prints, while Thomas Demand faces his studio as what one may as well call real life. Mostly, though, the show succeeds on a smaller scale, with modest surprises and ingenious pairings. An Edward Weston nude, meaning her buttocks, hangs between the Factory and the AIDS generation on one side and a plate of Brussels sprouts from 1900 by Charles Harry Jones, a British photographer, on the other. And who is to say which best represents Weston's gaze?

Man Ray in his orb may not be a crystal ball, but one can look for hints to the future in the surprises. Bajac makes a clear effort to include women on both sides of the camera, like Cindy Sherman out from under cover of the movies and the dirt. He has an unusual emphasis on European photography, as well artists not often known for the medium, such as Robert Rauschenberg, Kiki Smith, and Christian Marclay—the last, of course, with busted cassette tapes as part of his engagement with sound art. While the show does not catch up with contemporary artists straddling painting and photography, artists like Jacob Kassay and Eileen Quinlan, it expands its definition of photography all the same, to include video and film. Still not sure where photography at MoMA begins and ends? Then again, when Man Ray spoke of the laboratory of the future, did he mean the orb, the studio, the medium, or himself?

Fixed and variable

As for the object in the world, Civil War photography already conveyed a grisly reality that painting tuned out, especially with the development of stereograms that could be experienced as objects in themselves. Box cameras and darkrooms had a palpable dimension that was even harder to ignore. With a camera now in everyone's hands—and the felt need to confirm one's existence by deploying it—photography has merely come full circle. In "The Photographic Object," too, the object tends to objectify the human body, but for a more touchy-feely decade. If you could not decide whether Robert Heinecken most glorifies and degrades TV sets or human flesh, the show votes plainly for the latter. Only here that flesh need not belong to women.

In fact, nostalgia dictates that it belongs first and foremost to Astroturf and molded plastic. Ellen Brooks, who studied with Heinecken, uses the first as "leisure turf" for her couples, lolling in black and white over 3D forms. Robert Brown and James Pennuto use the latter for what could be raw earth, automobile bodies, or someone you know. Carl Cheng uses it, too, for other American fantasies in dime-store display cases, while Michael Stone puts his on sale racks, with images right off the TV. Jack Dale and Michael de Courcy stick to cubes, like actual black-and-white TV, while Dale Quarterman and Lynton Wells mount their portraits standing upright, like lazy spectators. If you lose track, Richard Jackson adds his social security and draft numbers to film negatives—and if you go hungry, molds by Robert Watts supply food.

In fact, nostalgia dictates that it belongs first and foremost to Astroturf and molded plastic. Ellen Brooks, who studied with Heinecken, uses the first as "leisure turf" for her couples, lolling in black and white over 3D forms. Robert Brown and James Pennuto use the latter for what could be raw earth, automobile bodies, or someone you know. Carl Cheng uses it, too, for other American fantasies in dime-store display cases, while Michael Stone puts his on sale racks, with images right off the TV. Jack Dale and Michael de Courcy stick to cubes, like actual black-and-white TV, while Dale Quarterman and Lynton Wells mount their portraits standing upright, like lazy spectators. If you lose track, Richard Jackson adds his social security and draft numbers to film negatives—and if you go hungry, molds by Robert Watts supply food.

If this all seems a very long time ago, where does one go from here? As it happens, the gallery and curator look in quite different directions. At its Chelsea branch, the same gallery borrows a room off to the side from Sterling Ruby, as if to rescue him from overstatement. Not every contemporary artist in "Fixed Variable" breaks the frame, but all eight are in search of sculptural presence. Letha Wilson does it with concrete ripping through landscape photography, John Houck with creased prints of visually active patterns, Kate Steciw with found images fashioned into tables or partitions drenched in ambient light, and Josh Kolbo with what might pass for photograms were they not Pringles and billiard balls—and if they did not hang like a shower curtain. Matt Keegan, Lucas Blalock, and Chris Wiley simply frame and manipulate images of gratings and architecture.

Color and mass need not exist apart, they argue, nor transparency and texture, no more than for "Photo-Poetics" at the Guggenheim. In contrast to the excess of the late 1960s, they make a case that formalism has an afterlife, even as the boundaries between media and genres are breaking down. The curator uptown, Olivier Renaud-Clément finds a similar lesson in a second show in Chelsea, by connecting photography's present to a deeper past. "Back Grounds: Impressions Photographiques (2)" sounds ever so quaint, and it includes nineteenth-century daguerreotypes of European ruins. It also has a selection of Equivalents, in which Alfred Stieglitz looked to clouds for an equivalent to abstract ideas, sensations, or photography itself. Yet they make a strong context for artists unwilling to choose among the three.

The one holdover from the 1960s, Chargesheimer's liquid silver, looks the most organic. And the one closest to Stieglitz, Sherrie Levine, just appropriates him—in her endless assault on "authenticity." They also look the least shadowy, the least sculptural, and the least alive. Liz Deschenes uses her photograms in slim industrial frames to reshape the room's architecture, while Gaylen Gerber drapes a curtain through it. Elsewhere Gerber, James Welling, and Martin d'Orgeval stick to movements across surfaces, with layered Plexiglas in bright colors, chemigrams, and photographs of cast shadows. Compared to Stieglitz, Deschenes, and "Fixed Variable," they approach formulas, but in the service of the viral object.

Photography has moved away from the object multiple times, not even counting spirit photography. With a Leica, photojournalism and street photography could become less reliant on a clumsy apparatus, while a photo's very claim to naturalize representation meant that nothing stood between image and vision. Yet photography also felt the pull to critique that assumption and to reassert itself as art, along with the medium as object. All three shows suffer from nostalgia for a pre-digital age, like a yen for vintage prints and fine leather binding. Still, they recover a sense in which photography means more than clicking. Someone struggling with the soot and glass of a cliché verre would have understood.

"A World of Its Own: Photographic Practices in the Studio" ran at The Museum of Modern Art through October 5, 2014, "The Photographic Object" and "Fixed Variable" ran at Hauser & Wirth through July 25, and "Back Grounds" at Andrea Rosen through August 9. The review of shows on the theme of object first appeared in a slightly different form in New York Photo Review.