Something Else Again

John Haberin New York City

Cindy Sherman's Robert Mapplethorpe

Lucas Samaras: Self-Portraits

Like the movies, artists and blockbuster exhibitions promise something larger than life. Yet art's fascination still lies in a very different promise. One remembers that moment of intimacy, that direct confrontation between viewer and something else. No wonder artists get uneasy when a critic teases out that moment with words. There is always something else.

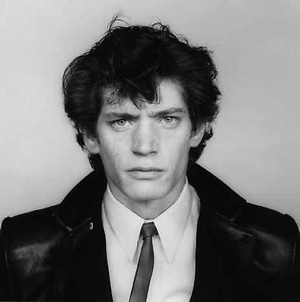

One can see it in their eyes. A memorable exhibition of Robert Mapplethorpe even calls itself "Eye to Eye," and it opens with a self-portrait, barely a year before his death in 1989, that shows little else. Meanwhile, in his retrospective at the Whitney, Lucas Samaras glares out again and again, with a disregard for propriety that boasts of the unvarnished truth.

Yet Mapplethorpe's self-portrait hides his identity, much as the closely cropped image, shaped much like a mask, hides his presence. The show may well offer a much fuller self-portrait of someone else again—Cindy Sherman, who made the quirky selections. As for Samaras, he never looks quite the same way twice, and in perhaps his finest image his own hands cover his face.

There is always something else—but exactly what? When artists expose themselves in public, it becomes harder than ever to say. Start with the whole idea of self-exposure.

Seeing through and talking big

So what else? In practice, art contains many others—the artist, the subject, the art object, oneself. In an installation, one may as well throw in the room, the institution, other viewers, and all their histories. Then again, one always knew they were there. Art lives on the borderlines between all these, and one never knows for sure which to call reality and which a work of art. Ironically, the most intimate act of all, reading, takes words and allows for fiction.

No wonder self-portraits get messy. At least since Jan van Eyck included a mirror within a double portrait, it has been hard to count the characters on display. Painting serves as a witness, but it also joins in the ritual.

The paradox may come with the very word exposure. It has connotations of taking off the wraps. One exposes oneself, which sounds honest and expressive. One exposes others, too, debunking them. Both contribute to the concept of the avant-garde. Modernism was born when art refused to hide the confrontation—between artist and art, between art and culture, or between subject and viewer

With Modernism, art turns from "just looking" to "seeing through." Instead of the harem for the Victorian nude or even Gustave Courbet with his fleshy nude with pubic hair, Pablo Picasso sees into a brothel, through the conventions of male ownership, and back into a viewer's eyes. More often than not, the gaze comes from an empty mask.

Seeing through demands juggling harsh, contradictory associations with peep shows and with getting at the truth. It shifts the technique of art from the camera obscura to a Joseph Cornell box. It shifts the materials of art and flesh from Courbet's oils to Meret Oppenheim's fur lining.

Seeing through demands juggling harsh, contradictory associations with peep shows and with getting at the truth. It shifts the technique of art from the camera obscura to a Joseph Cornell box. It shifts the materials of art and flesh from Courbet's oils to Meret Oppenheim's fur lining.

The contradictions do not stop there. Exposure also means the work of public relations, exaggerating the truth. In the same way, expression sounds frank, but expression has associations as well with big gestures, like a lie. At the other extreme from Cornell, big paintings share that dual fascination with personal immediacy and epic theater. Think of Caravaggio in Rome up to the Madonna di Loreto, Frederic Edwin Church contemplating Twilight in the Wilderness, Jackson Pollock doodling on the scale of a mural, or James Rosenquist turning his collage sketches into advertising billboards. Rather than just seeing through, art is also talking big.

Exposure, expression, and exaggeration

Self-portraits come laden with all these ideas of exposure, expression, and exaggeration. Iiu Susiraja in photography today turns these traits into self-questioning and confrontation. Long before, Rembrandt anticipates all this and more. In his early self-portraits, he dresses up and catches himself by surprise. In his late work, he invests the poverty of an artist's life with an air of majesty.

Conversely, portraiture implies an act of avoidance in the search for objectivity, like the blur in van Eyck's mirror. Everyone knows that the mirror in A Bar at the Folies-Bergère makes no sense, even when parsed by Jeff Wall. In the illogic of the reflected barmaid and expectant male displaced to the right, critics have seen a critique of everything from gender roles and café society to reality itself. As critics have also noted, Edouard Manet moved the mirror images further to the right as he worked and reworked the painting. They could mean, as they suggest, that he sought ambiguity, or it could mean instead that he fled from it, as sensitive as ever to criticism of his skill. After all, a more naturalistic, flat mirror would have to put the viewer into the painting—perhaps as the barmaid herself.

That does not mean all art means the same and plays the same game. Rather, art comes with a surfeit of shifting terms. When it comes to exposure, expression, and exaggeration as well, each work reshuffles the alignment and changes the rules of the game. Rembrandt does it in the course of a lifetime, as he changes from discovering himself in costume dramas to discovering an inner drama in a painter's humbler surroundings.

With Manet's mirror or Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, Modernism shuffles the pack again, facing down the viewer's gaze. From Chuck Close to Neo-Expressionism and appropriation art, later artists then turned back on the confronter. The artist's and viewer's dares alike had to live under the public eye. With Roni Horn, an actual movie star substitutes for a self-portrait, invoking the same intense fascination and endless transformations.

However, any decent art has to make its own alignment. The terms are always floating around, and art lines them up its own way. That is why others pay attention. Criticism needs all those words simply to keep track. Then, too, criticism has to keep on going because it never can keep track.

Cindy Sherman, Samaras, and Mapplethorpe definitely believe in exposure, expression, and exaggeration, art's one on one with the viewer, but not necessarily in the naked truth. At least Mapplethorpe's objects of desire do not don suits and ties, like Gilbert & George. Nudity and truth still exist, but always in new clothes.

Marriage license

Robert Mapplethorpe and almost anyone else sound like a particularly unlikely couple, even if Chelsea starts to accept gay marriage. Mapplethorpe and a feminist like Sherman sounds trickier still. The older photographer pushed the limits during his life but made a real scandal only after his death, when Jesse Helms noticed his homosexuality but not his perverse classicism. Sherman stood for a postmodern wave of appropriation and artifice, including a focus on heterosexual desire. Then she entered the museum without a whisper. Just this fall, her Untitled Film Stills became a gorgeous publication from the Museum of Modern Art.

Conservatives in Congress stumbled on Mapplethorpe's 1996 retrospective on its second or third stop. Or at least they waited until it hit a conservative enough town to raise questions of arts funding. Yet his work remains safely within paradigms of photography, like a curious cross between fashionable portraits by Richard Avedon and Diane Arbus's lost souls. Sherman helped bring feminism and photography into the artistic mainstream, while pushing Modernism and art photography into the past.

Mapplethorpe shocked his critics with nudity and sex. Sherman plays dress-up, and her characters invariably live alone. Mapplethorpe documented a life among outcasts—gays, blacks, and a woman body-builder, not to mention impoverished artists and dealers. Sherman takes her cues from Hollywood movies, including ones that have never existed outside her imagination. Mapplethorpe gives the most painful corners of his world a sentimental veneer, of glossy, black-and-white surfaces, sex, and flowers. When Sherman found her Untitled Film Stills too appealing, both to the public and to her own creative process, she started burying her own body in thick colors and in signs of disgust and decay.

In surely the best show this fall, Sean Kelly gallery pairs up the odd couple. It makes her the curator forand Mapplethorpe portraits. In the process, it makes everything I have just said about them sound suspect. Most obviously, Sherman makes one pay attention to Mapplethorpe. It makes me ashamed that I made it through a review of the old NEA controversy without once mentioning his work. In place of a freak show, she finds, much like Vivian Maier, individuals at risk. In place of nudity and sentimental artifice, she finds showing off and dressing up.

The show starts with rows of photographs that, not surprisingly, should make one think of Sherman herself. She includes plenty of strong women alongside the male genitals, and I do not mean just weightlifters. Artists such as Lee Krasner and Holly Solomon, the dealer, seem unsure whether to strut their stuff, to cower in a corner, or to maintain a worn dignity as best they can. One remembers not bodies but faces, perhaps enhanced by a fancy hat or boa. Nudity does appear, but most notably on the gallery's rear wall, where photos climb and spread like a Salon hanging gone mad. One sees even the flowers not as a kitschy sexual symbol or a greeting-card image, but as a momentary point of suspension between artifice and unveiling.

Less obviously, the show changes what one remembers of Sherman as well. It reminds one of her investment in culture—both popular culture's creative history, as in her actual work in fashion photography, and artistic subcultures of the 1980s. It takes something of the veneer of irony off her early images of sexuality. It takes her out from behind the camera, which is not to say that it makes her any plainer. Fittingly, one spots Mapplethorpe's little-known shot of Sherman herself over the desk on one's way out.

Yet another conservative nightmare

If Kelly bridges two poles of self-exposure, Lucas Samaras has more in common with the extremes. That may account for why I like him as little as ever after his Whitney retrospective. Still, he challenges the polarity with a vengeance.

Like Sherman, he has only one obvious subject, himself, and he sticks with it through his multiple disguises. Like Mapplethorpe, however, he sees nudity and degradation as the best and the glibbest disguise. Like both, he amasses in-your-face poses into an unnerving challenge. He confronts the viewer's sexual identity and the museum's cool distance, as if from art's perpetual centerfold. Does he succeed? Maybe it says something that the Whitney mentions only his native Greece, which he hardly knew, and avant-garde tradition, which he long outlived. He cannot force even the curators, it seems, to deal entirely with sex, drugs, and rock 'n' roll.

Like Sherman, he has only one obvious subject, himself, and he sticks with it through his multiple disguises. Like Mapplethorpe, however, he sees nudity and degradation as the best and the glibbest disguise. Like both, he amasses in-your-face poses into an unnerving challenge. He confronts the viewer's sexual identity and the museum's cool distance, as if from art's perpetual centerfold. Does he succeed? Maybe it says something that the Whitney mentions only his native Greece, which he hardly knew, and avant-garde tradition, which he long outlived. He cannot force even the curators, it seems, to deal entirely with sex, drugs, and rock 'n' roll.

Samaras starts drawing himself from his student days. At first, in fact, only the subject matter gives a hint of what Freud liked to call narcissism—the investment of erotic energy in the ego. He may echo the lean bodies and twisted poses of Egon Schiele in a Schiele self-portrait, but before long the twists, turns, and DayGlo color give him a style of his own. It looks very much a part of the psychedelic era or the ostentation of early gay culture. Samaras could stand for every conservative's nightmare of the 1960s.

By the show's end, one comes upon every medium from drawings and pastels to photos and assemblage. I have no clue how many hundreds of small works I saw, many titled by their date, as if to underscore the urgency of their making. Samaras seems to pun on Modernism's exhaustion. He seems to have no time to think, much less to take pleasure or to rest. In this art of immediacy, he turns again and again to Polaroids. He can only thrust an arm or dark brow toward the camera before he—or the medium—collapses entirely.

Conversely, the constant transformation creates a sense of distance, as if the artist's image served as one more token in a forgotten language. It makes sense that, for all the cultural signs and body parts, I know less than ever about his sexual preferences or personal history. He likes Polaroids, like Andy Warhol, in no small part because they allow the pigment to smear and run. At times, only the letter L or a mirror stands for the self. In a final room, an actual hall of mirrors draws the museum visitor into the portrait. Along the way, jewel boxes, encrusted with colored stones and filled with condoms and syringes, finish the trip from Cornell's peep-show to an urban freak show.

Samaras clings to his own body, even while he ties vision to dangerous and ephemeral desires. Unlike Mapplethorpe, he stakes his art on his survival. Unlike Sherman, who uses self-portraiture as a means toward disguise, he uses one disguise and one hiding-place after another as a means toward self-revelation. Maybe he needs Sherman as curator to rescue this provocative if uneven character for the present. In an artist's persona, as in life, there is always something else.

"Robert Mapplethorpe: Eye to Eye," curated by Cindy Sherman, ran at Sean Kelly through October 18, 2003, and "Unrepentant Ego: The Self-Portraits of Lucas Samaras" at The Whitney Museum of American Art through February 8, 2004. Related reviews look at Robert Mapplethorpe in retrospective, Samaras in pastel, and new media.