Tapestry

John Haberin New York City

Charles LeDray

boucherouite and Banners of Persuasion

"My life has been a tapestry." When Carol King hit the charts with Tapestry, she was only incidentally making a feminist statement, and she was definitely not singing about art. Maybe Miriam Schapiro and others had begun to recover fabric and folk traditions. Only a little earlier, neither might have counted as fine art. Now, though, the art world is singing along.

Actually, I like to remember the line as "my life has been a travesty," and the art world is capable of singing that, too. The recourse to global, multicultural, and household traditions has been fruitful and liberating. Still, the market can appropriate anything, and several recent shows help weigh the results. They range from the East Village to North Africa and back to Chelsea. They also range from the handmade to the commissioned and from myth to a man's sexually fraught coming of age.

At the Whitney, Charles LeDray makes "minor" art like fabric and toys into a bone-wrenching personal statement. In the galleries a few months before, "Rags to Richesse" celebrates globalization as simultaneously a recovery and disruption of traditions. Josh Faught again shows what a man can do with "woman's work," while a project called Banners of Persuasion has commissioned tapestries from well-known artists. Perhaps even the first is content to be a "minor artist" in a major gallery, and only the last is truly exploitative. All, though, are revealing. Related reviews look at antecedents in Renaissance tapestries and textiles by Henri Matisse, at Rosemarie Trockel, at Ann Shostrom, at women in postwar abstraction, at a fashion show from Eckhaus Latta as conceptual art, and at the collision between craft tradition and Pop Art in "Seductive Subversion," a show of women from the 1960s in Brooklyn.

Bright hair about the bone

Charles LeDray took on New York in a big way in 1991, with an installation of nearly six hundred objects. Yet I could forgive you if you hardly noticed. It must have seemed just another day in Astor place, just as East Village art had pretty much packed up and returned to Soho. Between street vendors and the homeless, when did used clothing not lay out on the sidewalk? When did the worn magazines on display not have a mix of arty and raunchy titles like Art, Adult, and Illicit—or the clothes, like pajamas, not come from apartments where no one seemed ever to have gone to bed? Even the title, workworkworkworkwork, announces an ordinary five-day week of barely confronting daylight.

Then again, maybe you missed it because it was so small. The magazines look like matchboxes, and the clothes seem meant for someone nearly small enough to fit in one. LeDray made them all by hand, from such spare parts as thread, carpet, cardboard, and magic marker. They anticipate the fashions for trashy installations, pattern and decoration, folk art, bundled thread, and outsider art. Perhaps he had caught a glimpse of the contemporary as a museum guard in, of all places, Seattle. Like his work ever since, they lay somewhere between comic and poignant, castoff and exquisite, childlike and anything but gender neutral.

Even now, LeDray is largely under the radar, despite classy representation by Sperone Westwater and, before that, Jay Gorney. The Whitney offers as much an introduction as a midcareer retrospective. In more ways than one, the artist is still trying things on for size, like the rows of hats in Village People—including a French military cap, a cowboy hat, a wizard's cap, a jester's cap, and a hot dog. His miniatures include glass shelves containing thousands of porcelain jars, turning progressively from bone white to bursts of color to pitch black. They include the juxtaposition in scale of stuffed animals in a toy chest, sugar cubes on lumps of black tar, and a tiny orrery in an oversized bell jar. Chillingly, the artist has fashioned the orrery, a cobbler's bench, and a grain of wheat from human bone.

Of course, he also trying on for size both adulthood and masculinity. He pairs lace and tiny male underwear, and military uniforms for the four services hang in the same room with a straitjacket on a tailor's dummy, a work from ten years later. It is hard to say which LeDray finds more confining. Freudians will delight in knowing that he is particularly interested in the role of the father, as with army fatigues and a biker's jacket labeled World's Greatest Dad. An early series of My Hands, My Father's Hands consists of little more than torn white fabric. Other men's jackets, some with the label Chas, suffer such indignities as tiny clothes suspended from the bottom or a gaping hole.

One can see visions of childhood almost out of Lewis Carroll, but with overtones of both gay pride and fears. A wedding ring on a skeletal ivory finger could almost quote John Donne's "bracelet of bright hair about the bone." The association of traditional clothing with untraditional male roles has a parallel in Gilbert and George, and Nick Cave has made similarly outrageous costumes, but the materials and metaphors obviously enter traditionally a woman's world. Kiki Smith might have fashioned the lumps of tar as female flesh, Laurie Simmons the toy chest as female stereotype, and Ana Mendieta the empty clothing as female abasement. Jewelry Window places milliner's materials behind a glass case, like black silhouettes by Kara Walker. The curator, Randi Hopkins of Boston's ICA, gives it an alcove much like a video, and one sits expecting the ghosts to move.

The show is not strictly chronological, but then LeDray keeps revisiting much the same things—along perhaps with the moment that he first realized he could not or should not live up to his father's expectations. The Village People are already at best a quaint memory, although HIV is not. Thankfully, though, he has left the cute stuffed animals behind, while keeping his sense of wonder and terror. The show culminates in a dark room with racks, tables, and dumpsters of worn clothing, neatly folded shirts, and actual neckties beneath drop ceilings coated with dust. The makeshift flea market on Astor Place has become, indoors at the Whitney, a cross between a department store and homeless shelter. Maybe a decent artist needs to remain something of an outsider to survive.

One bizarre bazaar

Can a genuine folk art survive globalization? Could it begin there? "Rags to Richesse" stakes its claim on just that paradox—and not just like Talia Levitt with rags. Starting in the 1960s, the Amazigh women of rural Morocco have felt everything disrupted—their nomadic ways, their craft traditions, and even the materials on which they rely. Their response? That tribal carpet one hoped to find has given way to a riot of fabrics, patterns, and colors.

Make that both senses of the word riot. The rugs do not discard Middle Eastern and African tapestry in favor of, say, political banners and product logos, no more than for David Alekhuogie. They in fact multiply the geometric patterns to the point of incoherence, from diamonds to checkerboards. Then they squeeze and swell the symmetries—or just abandon them two-thirds of the way through. Colors run to the comic intensity of Western advertising or psychedelia. Maybe both experiences helped produce the baggy edges and distortions. Other rugs have the flecked white of recent sculpture carved from book and magazine pages.

Textures are pretty funny, too. Faced with a shortage of natural fibers, women adopted cheaper ones along with cotton and wool. The fragments are tied as much as combed and woven, in what a show of craft at the Whitney calls "Making Knowing," giving the surface thickness of a long-haired cat in serious need of grooming. The gallery calls the results Pan-Moroccan, postmodern, personal, and feminist, but the North Africans call it boucherouite. It may sound like the crudeness of the French bouche (for mouth) or boucher (for butcher)—or (heaven help us) the Rococo elegance of François Boucher. Apparently it refers instead to rags and recycling. With rugs hung, laid, or piled every which way, the show looks more like a thrift shop or low-budget carpet store than a Moroccan bazaar.

Before one gets in too celebratory a mood, however, think of what one is celebrating. It enacts the disruption of globalization, like Lisa Alvarado, with the translation of nomads into urban or migrant workers, like Etel Adnan remembering a mountain or the South Africans in photographs by Zwelethu Mthethwa uptown at the Studio Museum.  It reflects increased demand from buyers schooled on reverence for authenticity, but also on color-field painting and Neo-Expressionism. Similar transitions in the past created industrial England and later sweatshops for women in New York's garment industry. The craft movement arose in part in response to the first—and a renewed appreciation for women's autonomy in response to the second. In fact, they paved the way for shows like these.

It reflects increased demand from buyers schooled on reverence for authenticity, but also on color-field painting and Neo-Expressionism. Similar transitions in the past created industrial England and later sweatshops for women in New York's garment industry. The craft movement arose in part in response to the first—and a renewed appreciation for women's autonomy in response to the second. In fact, they paved the way for shows like these.

Is this art visionary, liberating, commercial, or confining? Maybe all of the above, and it is well worth keeping them all in mind when thinking about art these days. Women's work, folk art, ethnocentric art, and self-taught art have all come into focus, as with the tapestry collage of Miriam Schapiro, and this gallery specializes in them. They inspire the hybrid forms of anyone from Dana Schutz, her Open Casket, and Rashawn Griffin to the torn canvas of Al Loving and the slash-and-burn comedy of Tracey Emin, and I could easily have included Ann Shostrum's torn abstractions literally hanging by a thread as well. Roberta Smith in The Times has defended styles like these as the future of painting, but the tapestry from Banners of Persuasion went on exhibit as both fine art and commercial exploitation. And Morocco has a long history as a crossroads for passengers with a lot of baggage—the kind who came to Casablanca for the waters.

Modernity has gone through all this before anyway. Besides the path from the craft movement to Anni Albers and the Bauhaus, its history included the "primitive" and Jean-Michel Basquiat. Janet Sobel exhibited both in outsider art fairs and as the first drip painter. No one with a grain of hope or sanity can visit "Rags to Richesse" and not see mostly the up side. Someone here is having fun, and it may as well include you. Just bear in mind that one is celebrating a hybrid, and if anything characterizes art's generation X, it is exactly that.

Under the rug

Banners of Persuasion really does have powers of persuasion. Last year the "London-based arts organization" asked well-known artists to try their hand at tapestry design. They have shown in London and at Miami Basel, and now a baker's dozen have come to New York. "Demons, Yarn, and Tales" speaks of the medium's history and relevance. This is, after all, the city of the Unicorn Tapestries, and feminism has made it more and more home, too, to folk histories.

Besides, New Yorkers know how to shop. Does Banners of Persuasion sound more like a definition of advertising than of art? It turns out to consist of Christopher and Suzanne Sharp, founders of the Rug Company—which, sure enough, produces and sells "homemade designer rugs." Nor will you find that out at the gallery, which sweeps it under the rug. Disrupting the boundaries between arts and crafts can have all sorts of implications, especially at an upscale gallery. A woman's work is never done.

For all that, each of the artists really does tackle "a medium foreign to his or her usual practice," and they would not have done it without this initiative. The collision of style and medium becomes the point, and it pretty much saves the show from cynicism. It loosens up Gary Hume, whose tracery in Georgie and Orchids recalls late Picabia. It lets Francesca Lowe indulge in a dark, earthy abstraction and Beatriz Milhazes in a flower opening outward, like a kaleidoscope. Jaime Gili's bright, jagged abstraction does not explode anywhere near as rapidly. They do worst, I think, when they stick to what they know—like Paul Noble's cartoon landscape, avaf and its Pop collage, or Julie Verhoeven's leftover Chelsea girls.

They do best when they bring something to home furnishings—a contemporary darkness. In A Warm Summer Evening in 1863, by Kara Walker, a black orphanage on Fifth Avenue is set ablaze. A black silhouette hangs headless over the shadowy period scene, like the victim of a lynch mob. Mappa del Mundo could pass for yet another Alighiero Boetti, right down to its Italian title. However, Gavin Turk has replaced the flag symbols with American product logos. Both works riff on one aspect of a tapestry, as embroidery.

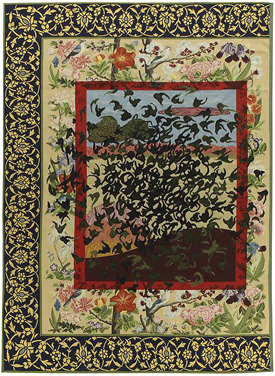

Still others take the form of a tapestry as content. The medium guides Peter Blake to a sampler, of the alphabet, but also to a grid and to text art. It leads Shahzia Sikander to a Persian carpet or to a park, calling for justice, but the borders veer off center, and black birds have turned the flowers into a perilous night. Up close, the birds vanish in interlocking hooks, and she calls it Pathology of Suspension. Grayson Perry stitches Vote Alan Measles for God on his border, presumably to protect America from the memories here of 9/11. Fred Tomaselli approaches the colors of a medieval tapestry, but birds perch in a black sky of leaves and droplets, like weeping stars.

For all that, one may leave with fears of a luxury product line—and an excuse to turn to Josh Faught for something more crotchety. He works in hemp, wool fibers, and sometimes traditional indigo dye. He adds pockets, like uncompleted sleeves or a site of organic growth. He also tosses in objects, like a dried flower or mystery novels sprayed black. Sometimes he gets flip and self-congratulatory, with allusions to lesbians and witchcraft, and sometimes just plain pretty. As last year in "The Horror Show," there is something comforting and scary about his work all the same.

Charles LeDray ran at The Whitney Museum of American Art through February 13, 2011, and Ann Shostrum at Elizabeth Harris through February 5. "Rags to Richesse" ran at Cavin-Morris through August 20, 2010, "Demons, Yarn, and Tales" at James Cohan through February 13, and Josh Faught at Lisa Cooley through February 14.