For Dear Life

John Haberin New York City

Peter Hujar and David Wojnarowicz

Two years out of high school, Peter Hujar photographed his favorite teacher. It makes a disarming introduction to his dark, joyful, and all too short career, at the Morgan Library—and, just two months later, to David Wojnarowicz in retrospective.

The teacher smiles, a little bashfully, as she holds up two fingers, with another touching her thumb. She could be teaching him another lesson, as a gay mentor to a gay rising star, or she could be playing along with him, exchanging the sign for horns they might place on one another's head. And Hujar was still at play nearly twenty years later—leaping across his apartment as if wondering whether he could fly. Both he and his schoolteacher seem young to the point of innocent, ordinary to the point of plain, and yet engaging to the point of a rock star.  So do a girl dropping a ball to see how high it will bounce, a cat perched on a cash register, kids on a swing, or a sun-drenched public garden on Hujar's first trip to Italy. So, too, does a clean-cut self-portrait (not in the show) from 1958.

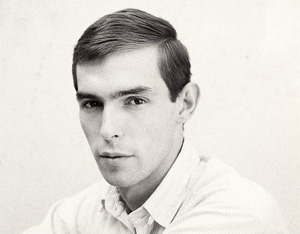

So do a girl dropping a ball to see how high it will bounce, a cat perched on a cash register, kids on a swing, or a sun-drenched public garden on Hujar's first trip to Italy. So, too, does a clean-cut self-portrait (not in the show) from 1958.

And then there is the photographer one knows from East Village art—the Hujar who would surely have cut class. Like Alvin Baltrop, he explored the catacombs where the dead lie poorly preserved and Manhattan's piers, where gay sex was an open secret. He photographed Candy Darling, the cross-gender star of Warhol's Factory, on her deathbed and a cat seemingly lifeless on a bed of leaves. A boy just off the rocky Italian coastline could be in mortal danger or at play. The curator, Joel Smith, arranges work by motif rather than year, for the slippery course of a lifetime. It runs to one hundred forty photos and samples from Hujar's fifty-seven hundred contact sheets, from a museum still establishing a presence in modern or contemporary art, as "Speed of Life."

You may remember Wojnarowicz as the promising artist who died of AIDS at thirty-seven and, briefly, Hujar's lover. You may remember him, too, as the gay male who channeled his anger, pain, and obsessions into A Fire in My Belly—the thirteen-minute film that he began in 1986. You may no longer remember the still younger artist, his future wide open, living on the margins and teeming with ideas. He posed with a mask of his own making, from Times Square and Coney Island to all-night diners and loading docks by the Hudson, as Rimbaud in New York. He painted over trash-can lids and movie posters because they were all that he could afford. Now all three stories converge at the Whitney, as (after a painting) "History Keeps Me Awake at Night."

Naughty and nice

Were there a naughty and nice Peter Hujar, fighting for prominence or simply to survive? One could put the difference down to AIDS and time, and he has little left of his innocence in a haggard self-portrait not long before his death in 1987. Nor does Wojnarowicz, as a lover and fellow artist, taking what might be one last drag on a cigarette. More often than not, though, a single work points in both directions. The cat on a register presides over a liquor store, while the cat on the leaves is sound asleep. Darling still looks glamorous and demanding, and a girl between the swings holds onto the pole above as if hanging on for dear life.

Susan Sontag lies confidently and comfortably on her back with her hands behind her head. She wrote the essay for Hujar's monograph, and her "Notes on Camp" could be about him as well with its theme of artifice and stylization. For him, as for a drag queen in Warhol's Factory, guilt or innocence alike could be a pose. Several figures pose under covers like shrouds for the dead, but the shrouds can include tinsel or ten-dollar bills. Madeline Kahn, the actress, could be a prematurely old woman or a fashion plate. His most frequent sitter, Ethyl Eichelberger, applies make-up as a drag queen.

Like Diane Arbus and Gordon Parks, Hujar started as a commercial photographer, and he did not give up fashion work until 1973. He relishes the high contrasts of studio photography in black and white, much like Irving Penn. Yet he was also a street photographer, in love with the quiet of Little Italy at dawn or the drama of Sixth Avenue's canyons by night. Arbus in fact complained that he copied her, and he took it enough to heart that he wanted to rethink his art. When a gallery exhibited him in 2011 with Nan Goldin, I spoke of his "keen eye for the strangeness of the city." Yet that misses something, too, for his is not a New York of freaks but of friends.

He arranged his last show, at Gracie Mansion in the East Village, in two long rows as a motley compendium of friends—from Louise Nevelson cuddling her dog to a pregnant nude, a day on Fire Island, and a horse. When he approaches politics, a gay liberation march looks less like a parade than a party. When he approaches sex, which is often, his cast looks as vulnerable as ever. A man sucks his toe, while another leans back against his shadow, lost in thought. Others curl up with their butt facing the camera, like subjects for Hans Bellmer brought out of Surrealism and into the realm of the personal. These are their moments away from the furor.

Their AIDS crisis betrays neither Goldin's anguish nor the self-assertion of Janet Cooling, Gregg Bordowitz, Robert Mapplethorpe, and Mapplethorpe portraits. Hujar's seventy friends at Gracie Mansion may sound like Mapplethorpe's Fifty Americans, but he never claims to speak for America. He speaks instead to his puzzlement at living among equals yet in a theater. In his most shocking image, Bruce de Ste. Croix looks too small for the room and too large for the chair as he holds his erect penis. He seems to look on it as a stranger—a feeling that men know all too well. Yet he must have got it up for the camera.

As for his one-time lover, lots of things kept David Wojnarowicz awake. The piers and loading docks at night served as sites for gay sex (and as a work of art for Gordon Matta-Clark), and he made a meager living for a while offering it up. He must have loved the night, too, for the energy of East Village art, where he found his first audience and a home. As for history, he could always declare his own. The early photos and their titles allowed him to identify with Arthur Rimbaud, but also with Jean Genet, William S. Burroughs, and Joseph Beuys. The white mask of Rimbaud, also on display at the Whitney, becomes a death mask.

The fire next time

The series took him to the streets at age twenty-four with his own graffiti for captions, like "The Silence of Marcel Duchamp Is Overrated." For Wojnarowicz, any silence is overrated, even before the AIDS crisis meant "Silence = Death." His obsessions were everywhere on display in a packed, unruly retrospective at the New Museum in 1999, seven years after his death. And the film caused a scandal at the National Gallery on its way to the Brooklyn Museum in 2012, in "Hide/Seek"—as footage of Mexico's Day of the Dead gave way to ants crawling over a crucifix. You will excuse me if I had may say on both occasions and focus here on the Whitney. It puts his lives in order at last and gives them a torturous but convincing shape.

The museum follows his arc from promise and madness into anger and mourning. A turning point comes in paintings from the early 1980s. They serve as history paintings, on a large scale, but with the sharp colors and heavy outlines of a comic strip.  Y(A still larger painting appears along with installations at his Chelsea gallery.) Connections and disconnections run from politics and pig meat to train wrecks and a snowman in hellfire. The old world really is dying and a new world unable to be born.

Y(A still larger painting appears along with installations at his Chelsea gallery.) Connections and disconnections run from politics and pig meat to train wrecks and a snowman in hellfire. The old world really is dying and a new world unable to be born.

The anger and mourning take over for good with death everywhere before his eyes. Where a painting had declared The Death of American Spirituality, death has become a pressing matter of material decay. It appears as metaphor in footage of a bullfight, a cock fight, and professional wrestlers. It appears directly in harrowing photographs of Peter Hujar moments after his death. Wojnarowicz could see his own coming soon. He surrounds a snapshot of himself as a child with plenty of text in protest—beginning "One Day This Kid Will Get Larger," just in case you hoped that he would go away.

There are continuities all the same. From the start, Wojnarowicz plays the outsider, which he called "his true subject." He adopts Rimbaud as not just a poet, but also, the Whitney points out, the speaker of Je est un autre. ("I is an other.") He is always an admirer of the Beats, much better at free association than composition, just as in the paintings. The curators, David Kiehl and David Breslin, leave A Fire in My Belly to a screening room as just one film among others, as if to rub in the overflow.

He is also political from the first, on the subject of outsiders well beyond gay artists. He set out twenty-three Alien Heads in 1984, in painted plaster, as testimony to refugees and human-rights abuses in Central and South America. The heads, gagged or garish, obliterate the distinction between torturer and victim. They also match the number of chromosome pairs in human DNA. Again, even protest depends as much on emotion and the imagination as a narrative and the facts of life. Wojnarowicz with a crucifix was, after all, a lapsed Catholic—like another artist who raised a scandal in Washington, Andres Serrano with Piss Christ.

His affection for Hujar could be the most enduring and poignant continuity of all. Hujar photographed him, handsome and healthy, and Wojnarowicz in turn painted sloppy but exuberant portraits in 1982, including Hujar Dreaming. He wanted to make a film about his friend as well. He also dedicated a painting to him at Gracie Mansion—among four paintings for The Four Elements in 1987. Earth, air, fire, and water could well sum up his obsessions, but Wind looks unaccountably serene. It just happens to include a helpless infant and yet another city in ruins.

Peter Hujar ran at The Morgan Library through May 20, 2018, David Wojnarowicz at The Whitney Museum of American Art through September 30 and at P.P.O.W. through August 24. Related reviews look at past work by both artists, plus the controversy over the Wojnarowicz film in a group show in Washington.