4.2.25 — Above It All

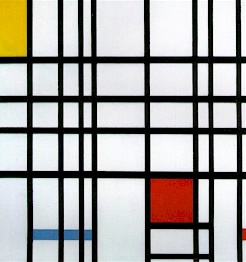

Piet Mondrian can seem above it all, and perhaps he was. His abstract paintings make no concession to the viewer—not the enticement of color or hints of people, places, and things. You must value them for what they are. They are not even “in your face,” like the sharp brushwork of Willem de Kooning or the nasty smiles of his women. In one of his earliest works, though, he really is looking down from above, as the earth and sea sharply curve away. Find your footing if you can.

Mondrian’s planet leads off a focus exhibition of just thirteen works at the Guggenheim, drawn from the museum’s collection, through April 20. It is not an oval, no more than his Ocean four years later, in 1914, for it fits nearly and properly into a rectangle. He makes clear, though, that the painting reflects the curve of the earth itself. He is painting a dune in Zeeland, in his native country, where the ocean is never all that far away.  He has come to the westernmost province of the Netherlands, also its least populous, but then who would dare populate his art? Patches of undistinguished color set off its elements. And then the warm blue of sea or sky looms up to fill out the canvas, much as Mondrian itself finishes off Ocean in monochrome.

He has come to the westernmost province of the Netherlands, also its least populous, but then who would dare populate his art? Patches of undistinguished color set off its elements. And then the warm blue of sea or sky looms up to fill out the canvas, much as Mondrian itself finishes off Ocean in monochrome.

He would never allow his subjects to divide a canvas, but he is still disrupting things. The Guggenheim has just two of his more famous compositions, from 1922 and 1939, their thick black lines containing and failing to contain upsetting fields of red, yellow, and blue. In one, the black stops just short of an edge and could well have begun elsewhere. Mondrian also turns squares to create diamonds, where the sense of cutting things off at the edge is that much more apparent. He may omit color altogether, leaving nothing to slow the collision of line and field, black and white, and yet everything is, pointedly, complete. It is, as he called his idea of an art movement, simply De Stijl.

It may not make compromises, but is it austere? Not when the colors and lines keep coming, and not when a diamond in black and white can hang high on the wall like the iconic monochrome of Kazimir Malevich in Soviet Russia. Not, too, when he could adapt to exile in New York with his late Broadway Boogie Woogie, now in the Hague. How did he get from Theosophy, an early interest, to jazz? How could he not? One could almost call his entire body of work a matter of theme and variations.

Is it consistently abstract? Not that either, although a modest success allowed him to quit work on still life. Still, he found his first mentor in an uncle, a still-life painter, and, like Georgia O’Keeffe, he drew both abstraction and single flowers. Like hers, they come alive from a point of view up close, which allowed him, he felt, to focus as ever on line and structure. A blue wash made some of them easier to sell, but color once again can seem incidental. Love them for themselves or as a step toward abstraction.

A selective show like this one can challenge what you thought you knew while summing up a career. But then a 1996 Mondrian retrospective at MoMA did both already. It came a long time ago now, not long after I began this long-running Web site. It changed my mind about him and allowed me also to explore whatever “theory” concerning Modernism was in the air. Allow me, then, not to begin over again, but to invite you to read on from the link just now. Here I focus on the Guggenheim in focus.

Just how, then, did Mondrian get to abstraction? The story does not run in straight lines, unless you count Mondrian’s black vertical and horizontal lines of varying thickness. His Ocean seems to mark a transition from his earthscape in Zeeland. He constructs an ocean from a dense array of black crosses, like piers, but also like his later black. A still life centers on a flower pot on a crowded table—and then a painting nearly identical in size makes the pot its sole clearly recognizable shape. Yet he painted both the same year.

Was this a constant back and forth or a turning point? There is no denying the primacy of his later abstract art, although he also called it Neo-Plasticism, for it, too, was malleable and changing—not uniform, but in balance. Still, look again at his earth view to see what was already in place. Its curves refuse a familiar point of view, much as the Mercator perspective in an atlas must squash a globe onto the page. Mondrian’s abstract art is a similar challenge to the single-point perspective since the Renaissance. It is his inhuman perspective on Modernism and New York.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.