Keep Your Distance

John Haberin New York City

The van Gogh Museum and Museums After Covid-19

It has taken museums so long to return that I could almost have forgotten why I need them. Still, is that all there is to reinventing museums after Covid 19—reopening doors?

Imagine that you could have van Gogh and his Sunflowers all to yourself, any day of the week. Emilie Gordenker could, even in this age of museum crowds and museum blockbusters. As director of the Vincent van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, she found herself in charge of a museum on lockdown. It was not what she had in mind when she assumed the post just three months before.  Suddenly, she had far more on her mind than the chance to get to know it intimately. Like all directors and curators in a pandemic, she faced drastically reduced revenues and an uncertain future.

Suddenly, she had far more on her mind than the chance to get to know it intimately. Like all directors and curators in a pandemic, she faced drastically reduced revenues and an uncertain future.

Like them, too, she faced a new responsibility, to plan for a museum's return—and not at all as it had been. What could it become, and could she extend a director's privilege to everyone? Can museums everywhere, to create a future for art? It may take more than social distancing. As I discovered all but alone at the Museum of Modern Art, safety may be the first priority, but it cannot be the only priority. What happens to a museum without the crowds or after they return?

The two women were obviously enjoying each other's company. They may even have enjoyed the art, as one took the requisite selfie in front of Starry Night. And then they moved on, and MoMA's most popular painting stood alone. If Gordenker had had van Gogh all to herself, now of all things so did I. It was part of the pleasure of museum reopenings after nearly six months of lockdown—a year longer at the American Folk Art Museum. What does it say, though, about what lies ahead for visitors and art institutions alike?

Alone with van Gogh

Two days before its report on Amsterdam, The Times spoke instead of physical safety. The van Gogh Museum had reopened the first of the month, after eleven weeks. (For a depressing contrast, New York had not so much as entered "phase 1" of its recovery, galleries had no firm date, and museum reopenings lay untold months away.) Still, the need for masks and museum social distancing has not gone away. Not so long ago, the museum could count on six thousand visitors a day—eight times the number it could now allow. Like restaurants and other danger points, it also faced the challenge of luring them back.

Under lockdown, most museums would rather think of other things, and so would many arts writers. The press focused at first on staff cuts and endowments. It duly reported canceled summer schedules and, later, shameful plans at the Brooklyn Museum to deaccession major works. It cannot speak to planned fall exhibitions, because museums themselves hardly know. Ambitious retrospectives will have locked in promises on all sides, of loans and insurance protections, but who knows? And who has the time or the optimism to speak about opportunities?

Still, who can help hoping for change? Years ago, at age eighteen, friends and I ran like hell through the Vatican for a chance to see the Sistine Chapel before the crush. Ten years later, daunted by the mob scene in front of the Mona Lisa, I stuck to the opposite wall, where the rest of the Italian Renaissance would more than do. (The Louvre has since thought of moving Leonardo to his own remote room—not so much solving the problem as putting it under quarantine.) And that was before selfies and a popular culture more at ease with art. The Brooklyn Bridge in April was a joy, but could it make up for the New York I had lost?

Naturally the Times made its report all about Gordenker, to humanize the big issues in that tried and true formula of mainstream journalism. In a lead photo standing out front, she has the whole museum to herself—she and unseen reporters, photographers, and colleagues. Another photo shows an empty room with the most majestic of Sunflowers on a wall to itself closest to the camera, as if for you alone. Vincent van Gogh, who sold nary a painting, must have seen it that way. I still think of it that way, too, as simultaneously a construction and a vision. Will fewer visitors, then, translate into greater insight and pleasure?

One can always hope, but the photo shows something else as well, markers for where to stand, six feet apart. Even if one could overlook them, a caption points them out, but who could? Distancing only makes one more aware of others and more aware of where one cannot go. Once people get over their fears of infection, decreased museum capacity is sure to mean long waits, too, quite on top of timed tickets. I am looking forward to the first days of New York restaurants, when it will be easy to get a seat, much as I am looking forward again to seeing art. And then I am bracing for what comes next.

Can museums help, then, or will it be business as usual, for all their best intentions, even after MoMA's "fall reveal" in 2020 and again in 2021 and the Frick Madison in 2021? Gordenker, as it happens, came to the van Gogh Museum from the Mauritshuis, the collection of Dutch art in the Hague, while her predecessor moved to a museum in London. It sounds like musical chairs, if not musical floor markers. One may be used to getting close to a painting and to stepping back at will, to keep experiencing it afresh and as one's own. All art, even conceptual art and mechanical reproduction, turns on enveloping detail and the big picture—as part of the twin demands to look and to think. Between hard lines and long waits, can art still embrace both?

Apart from the crowd

To be sure, the director of the van Gogh Museum had taken measures to share her experience and to protect others. So too have museum directors in New York. While none has taped off every other work or placed marks on the floor, MoMA and the Whitney Museum require timed tickets to monitor capacity, while the Met sells advance tickets and requires reservations. Signs encourage one-way traffic in galleries designed for anything but. Guards call rigorously for masks to cover your nose, even as social distancing goes without saying. They are practicing crowd control without the crowds.

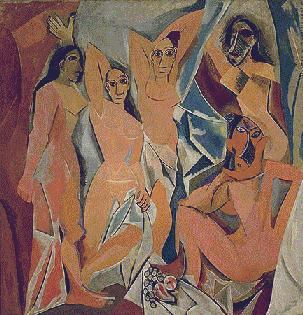

I had been to the Met the week before for the thrill of Jacob Lawrence, "Making the Met," and the return to museums, while wondering if there is any going back. I had rediscovered what is lost in a virtual museum, and I have already tried to share it with you. Now I ventured into MoMA to see whether I or anyone else could grasp Covid New York and art after Covid-19. I could have Les Demoiselles d'Avignon to myself, too, with no one to shield me from the shock— or a painting by Faith Ringgold to its side, looking less shocking than playful out of its time. Sculpture by Alberto Giacometti once again confronted me head on (and he will be back soon paired with Barbara Chase-Riboud), but in a gallery as empty as the mysterious space between its hands. As for an entire floor of postwar art, it might not yet have found a public.

or a painting by Faith Ringgold to its side, looking less shocking than playful out of its time. Sculpture by Alberto Giacometti once again confronted me head on (and he will be back soon paired with Barbara Chase-Riboud), but in a gallery as empty as the mysterious space between its hands. As for an entire floor of postwar art, it might not yet have found a public.

I could have been just out of college again, teaching myself modern art a room or two each week, back when the only encounter that mattered was between me and the work. Crossing the Brooklyn Bridge in a pandemic has been like that, too—a reminder that New Yorkers could once call so much more of the city their own. Again, though, there is no going back. As the shock wore off, I found myself drawn to performance footage, because it was immersive, and I need not feel so alone. It also has a welcome focus on women, like Joan Jonas erasing her own starry gestures, Martha Rosler making the kitchen a battleground, Nancy Holt putting herself on a par with ancient sculpture, Hannah Wilke more stylish in her confrontation, and Anna Bella Geiger struggling with her body and her sweater. Andy Warhol, lest one forget, invited plenty of women to take over the Factory.

They have more to show for themselves than nostalgia for baby boomers, although Shuzo Azuchi Gulliver gets away with just that in Cinematic Illumination. His 1969 slide projection onto a circle, meant for a Tokyo discotheque, mixes found images, points of light, and rock classics for a literal surround sound. Eager to have it to yourself, too, or starting to worry? Arts coverage has, as always, fallen back on the obvious: museums are reopening, but will anyone dare to come? Not many, perhaps, but do not get your hopes up.

For one thing, this was the last week before Labor Day, when the city always empties out. It was also a time of limited travel, period—and too late for those willing to travel to change summer plans. Besides, it takes blockbusters to draw crowds, apart from the Mona Lisa and van Gogh, although MoMA's 2019 expansion shifts welcome attention to the collection. Now museums are just catching up and marking time. The extended run of Félix Fénéon has just one famous painting, by Georges Seurat, in only a study at that—and Donald Judd upstairs gave up painting entirely. Social distancing may soon bring the opposite experience, of long lines, but whether they will be long enough to cover museum finances and to expose enough people to art remains to be seen.

The New York Times reported on the van Gogh Museum on June 14, 2020, and The Museum of Modern Art reopened September 1. Shuzo Azuchi Gulliver ran through February 28, 2021. Related reports have looked at Covid New York, art after Covid-19, galleries after Covid-19, and reopenings at the Met.