Pop's Subversive Seductions

John Haberin New York City

Women in Pop Art and Campaign

Pop Art posed some good riddles. How could art have become so cool, while turning to the pleasures of American culture? Did it care if it was seductive, and was it desiring or subversive? Oh, and why were men doing all the desiring and subversion?

A show of women Pop artists would sure like to know. It would also like to know if they really Pop artists. A year later, that label could apply to the twenty-seven artists in "Campaign" as well. So what if they are two generations younger, and several are men? After all, it is hard to start a campaign without camp.

Late for the party

Why Are There No Great Women Artists? did more than ask a question. Linda Nochlin's title made a demand—or rather, two of them. She asked for a history with women included, and she began one. Yet she also asked what had kept women from making great art, and in the process she put the whole idea of the solitary, dedicated artist under suspicion. Art could use more of that suspicion today. Not that artists deserve less than solitude or dedication, but some galleries today make a poor excuse for either one.

She also wrote what sounds in retrospect like an amazing Pop Art painting. I can imagine the words popping brightly from canvas, less like the conceptual spareness of Lawrence Weiner or the political rigor of Jenny Holzer than like Deborah Kass or Ed Ruscha. Come on, girls, lead us into temptation—and if you slam us for it, so be it. The Brooklyn Museum in fact calls its alternative history of the early 1960s, "Seductive Subversion," and it is as much concerned with broadening the picture than with challenging it. James Rosenquist, Robert Rauschenberg, Wayne Thiebaud, Thiebaud drawings, or Andy Warhol and Warhol's influence hardly looms over the action. In fact, they may never come to mind.

One can see Pop Art as the collision of American culture and modern art's expectations. Yet the artists here come from England, Canada, Sweden, Austria, Belgium, Argentina, Japan, and Venezuela by way of Paris. When Pauline Boty, a Brit, tries her hand at a film poster, she features the French New Wave in Jean-Paul Belmondo. Conversely, Modernism's hard edges and materials give way to Joyce Wieland's crafting, Dorothy Grebenek's hooked-wool rugs, Kay Kurt's glycerin and candies, and May Stevens's Big Daddy paper doll. Faith Ringgold already provides a folk ancestry, but through her sophisticated imagery. The Pattern and Decoration movement begins here.

They also come late to the party—with less the anxiety of the bomb and the Cold War than the free-for-all of the Summer of Love. Marta Minujin joined in "happenings," although her DayGlo assemblage here offers an only mildly threatening pillow. Yayoi Kusama conducted her own, parading on video halfway between nudity and glitter. Her armchair of tubular growth positively demands the adjective touchy-feely. Evelyne Axell's flatly painted legs and breasts also have the color scheme of a Beatles poster, and Jann Haworth actually created one. She worked with Peter Blake on the cover of Sgt. Pepper's.

Naturally Blake almost always gets credit, and the show wants to change that. And Patty Mucha, then the wife and collaborator of Claes Oldenburg, contributes both to the art and the catalog. However, the curators, Sid Sachs of Philadelphia's University of the Arts and Catherine Morris, look more to the future. They ask less how to see Pop Art than how Pop Art would look if it had included women. It would look less detached, more personal, more confused about the distinction between painting and installation, and more multicultural. It would look, in short, more like art today.

It would definitely include race. The busty black sculpture of Niki de Saint Phalle appears along with Ringgold. Another step, and one would reach such contemporary artists as Shinique Smith, Mickalene Thomas, and Kara Walker. Awkwardly and appropriately enough, the show seems to continue without a break into the rest of Brooklyn's Sackler wing. It could be begging for a replay of the wing's drabber and more hectoring opening show, "Global Feminisms." At least one can get out without another look at Judy Chicago and The Dinner Party.

From anger to seduction

The seductions are there, at the selection's most subversive. One can see them in the titles of Kiki Kogelnik's Come a Bit Closer and Dorothy Iannone's I Love to Beat You. They run from culture of the 1950s, with Rosalyn Drexler's Chubby Checker, to the 1960s, with Barbro Östlihn psychedelic sunflower. Marjorie Strider's beach girl comes closer to Roy Lichtenstein and her mouth pruriently consumed with an intensely red radish comes to Tom Wesselman. Less subversively, Grebenek's dollar bill and Chryssa's painted cent sign come out of Pop Art's seductive playbook. Small change went a lot further then.

The anger is there, too. Drexler calls another painting Love and Violence, and Axell calls hers Rape of Ingres. It puns on the nude, a Pop rendition of J. A. D. Ingres. It also puns on Le Violin d'Ingres, a nude with the sound holes of a violin on her back by Man Ray. In case you have forgotten, his altered photograph is itself a double pun, an idiom meaning obsession—or maybe I should go back to solitude and dedication. Mostly, though, the artists pretty much enjoy Man Ray's seductions and obsessions.

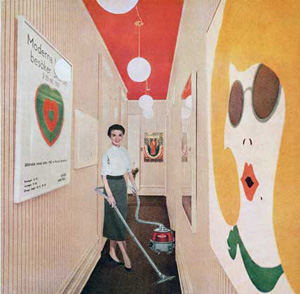

Martha Rosler with her feminist and antiwar collage is plenty angry and justly famous. Yet it, too, embraces its place on the margins. Her eternally smiling woman Vacuuming Pop Art could be asking the same as an English artist, Richard Hamilton: Just What Is It that Makes Today's Homes So Different, So Appealing? It is also late in coming, completed in 1972. A more feminist art and the appropriations of the "Pictures generation" are on their way.

Some of the most overtly political art dates the most. Idelle Weber had already grown more impersonal in style, on her way like Melanie Vote to the photorealism of her later years. Her silhouettes on escalators attest to a hatred of mechanical motion and public spaces. Their yellow background also seems to set them in a distant modernist past, along with Mara McAfee's Marvelous Modern Mechanical Man. Those were the years of "organization man," but also a finer and less didactic rebellion. Warhol's haunted electric chair had already shown what real fear means.

Marisol takes John Wayne for her boxy wooden sculpture, another bridge between Pop Art, folk art, and woman's work. She also looked good, and the curators make a point of how much appearance counted in a man's world. Still, the international cast signals a loosely defined world. More than two rooms with more work by the better artists would not have changed that world, though it would have helped bring definition. "Subversive Seduction" tells not a great or even cohesive story, but an honestly subversive one all the same. It is also comes at a good time for reviving the Brooklyn Museum, which considers diversity and outreach as its mission, while running itself into the ground.

In two of the exhibition's finest moments, the seductions and subversions lose their roots in Pop Art all but entirely—although they reassert themselves in "New York: 1962–1964." at the Jewish Museum. Lee Lozano paints a gun as a loose penis. It shares its raunchy assertion with screws not in the show, by Judith Bernstein, and its demands with the present. Vija Celmins, known for her near-abstract seascapes in pencil, here contributes harder edges and a harder pencil—a sculpted and painted one. She reverses Oldenburg expectations for soft and hard. She also asks anyone, including a woman, to begin her own drawing and her own narrative.

Smear campaign

I have to like images of women when men have the last word. Of course, I would say that, but I am not altogether kidding when it comes to the images of women in "Campaign." Side by side in Chelsea, Glen Fogel and Adam Helms display the most direct and haunting series of women's faces, but also the most elusive and divided. Fogel rips the same face from a magazine three times—once seemingly in plastic wrap, once with the word SLUT on her forehead in red as if disfigured for life, and once scratched entirely away. Helms ups the ante to eight faces, in varying densities of screen-print dots that come temptingly close to reality or to beauty as one approaches or steps away. Like William Copley, they might treat image making to preservation or disfigurement, to male longing or naked aggression, and to a woman's self-obsession or all too real sense of abuse.

Is this the same Fogel who once displayed a plywood fort, like an overgrown boy? Is he joined by Hank Willis Thomas, who has struggled with black male identity—and now serves up a "chorus line" titled Alive with Pleasure!? How about Clifford Owens, who poses naked himself in performance, along with his audience? Collages by Derrick Adams include African American women in profile, like Egyptian queens, but would they work as streetscapes in tribute to Romare Bearden or as portraits after Emma Amos? All of the above, but in "Campaign" they truly do speak to gender and, in fact, to women.

Of course, men, too, belong to a culture obsessed with celebrity, lifestyle, and image making. This is not, however, about their anxieties and their self-image. When Deville Cohen arranged men supporting a car body, he could have been putting them through their paces, but one saw only their legs and high heels. Now they get along just fine with his poster girl—and the hand reaching up from her inflatable raft. The curator, Amy Stewart-Smith, has worked on "Greater New York," MoMA PS1's show of emerging artists in 2005, and "Civic Action," plans for Long Island City at the Noguchi Museum right now.  She approaches gender with the same concern for alternative contexts and visions.

She approaches gender with the same concern for alternative contexts and visions.

That double-take applies to women as well. With a fragrance called Revolution!, in a display case with some suspicious debris, Lisa Kirk could be speaking to femininity or to class. And now I can look back at her 2009 performance piece, a woman selling real estate, as about the performer or the real estate. With her blond girls debating the Iraq War or their own inner lives, Amy Wilson has mixed politics and innocence. Here, though, a sparer cast on brown paper does take up fashion, and suddenly her earlier work belongs less to folk art and more to gender as well. Laurel Nakadate still dwells on Gen Y tears, but here she seems at least a little more grown up.

Sometimes the shift in focus is obvious, as for Nida Abidi's woman in black, posed between Britney and Islam. Where Aleksandra Mir once compiled records of global inequality, here a wall sketch charts the "evolution" of a naked being—from a child to a shapely woman to a heavy blob on the floor. Sometimes it is not. Jill Magid surrounds a slim neon curve with words punched into Sheetrock like bullet holes, the text referencing a theorist of killing, and I am still trying to figure it out. Sometimes "Campaign" widens an artist's perspective, as when Kate Gilmore now poses alongside other women, from fat to slim, each stuck in her own pink arch. Sometimes it tones things down, reducing Mika Rottenberg and her video wrestlers to traces of butt and hair, in place of a woman's eyes and mouth.

The show starts almost quietly, give or take a poster outcry from Kathe Burkhart and Hrafnhildur Arnardóttir's artificial legs and artificial hair sticking out from a balcony. (On my second visit, the legs had vanished, but then she and several artists use the show as a performance set now and then.) Jen Denike's Girls Like Me, fondling or sucking each other's feet, look downright restful. A second room gets raunchier, as in Fay Ray's wall-size array of photo boxes with eyes, lips, and other organs piled like petals. Somewhere in between, Shana Moulton gives herself a class in make-up and skin care, in preposterous caked mud and bright colors. Like everyone in fashion's smear campaign, sometimes an artist has to cover up.

"Seductive Subversion: Women Pop Artists" ran at The Brooklyn Museum through January 9, 2011, "Campaign" at C24 Gallery through February 25, 2012.