The Blockbuster and the Bowery

John Haberin New York City

Alan Solomon and New York: 1962–1964

Changing Spaces: Just Above Midtown

Alan Solomon came to New York from the polite reaches of academia to direct an institution dedicated to memory. It was 1962, when a museum itself must have seemed a blessèd relief. Yet Solomon threw himself into the turmoil of the city and the Jewish Museum into the turmoil of contemporary art. For just three years, he put the museum at the center of both.

Does anything else set those years apart? "New York: 1962–1964" is content with that, and it makes for a wide-open exhibition. It begins far from the museum's mansion on the upper reaches of Museum Mile. It wallpapers the entry with photographs of Eighth Street, plus an actual "Don't Walk" sign and the marquee from a liquor store on the Bowery. It could be a direct rebuke to those who equate the city with midtown, on their way to Sidney Janis gallery or the Museum of Modern Art,  and Solomon was out to rival them both. His childhood in Quincy, Massachusetts, education at Harvard, and years at the Cornell University art museum must have felt a long way away.

and Solomon was out to rival them both. His childhood in Quincy, Massachusetts, education at Harvard, and years at the Cornell University art museum must have felt a long way away.

But wait: and here you thought that New York had been dethroned from its place at the origin and center of the art world. Surely museums have been looking everywhere but New York, for what conventional histories have willingly overlooked. Maybe so, but it was still the place to be for Solomon and the artists he knew. He also, it turns out, found a more diverse city than its critics remember, a diversity inseparable from the excitement and the challenge. The Jewish Museum recreates them both.

"Are we really that different?" For Linda Goode Bryant, there was only one way to find out—to found a black-run gallery for black American artists. Should the Jewish Museum, briefly at the center of contemporary art, have renamed itself Just Above Museum Mile? Ten years later, this was Just Above Midtown. The Museum of Modern Art follows it from 57th Street to Tribeca, when the downtown neighborhood was a home to alternative spaces, and finally Soho, when the gallery scene was exploding. If it closed after twelve years, a victim of rising rents and unpaid bills, it had given plenty of artists a lasting start.

New York, New York

Janis had its own show then of "The New Realists," the Guggenheim its "Six Painters and the Object," and MoMA (in a follow-up to is fabled "Sixteen Americans" in 1959) its fifteen "Americans," mostly New Yorkers. But then the Jewish Museum staged "Toward a New Abstraction," with Frank Stella and Kenneth Noland, and "Recent American Sculpture," with Lee Bontecou, John Chamberlain, and Richard Stankiewicz. It had the first ever retrospectives for Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, neither one out of his thirties. Solomon took the same spirit to Europe as well, as U.S. commissioner for the 1964 Venice Biennale. Naturally he insisted on large work and took over a spare building to accommodate it. And naturally Rauschenberg won first prize.

First things first, though, and that means New York. Solomon could not think small with a big city at his feet, and its seediest street will not be your last immersive environment. The museum devotes both its exhibition floors, a rarity, the first with an open plan and the second with separate rooms for the civil rights movement and, finally, the Biennale. Neither, though, distinguishes art from context. Photographs hang salon style, not side by side, as do covers from Time, Life, and Ebony. Frank O'Hara, John Ashbery, and Amiri Baraka (then Leroi Jones) read their poetry aloud.

The first cluster of photos introduces New York, as raw and welcoming. Diane Arbus captures cross-dressers backstage and a couple on a pier with a sad hint of Lady Liberty, Weegee a One-Way sign that has lost its One if not its way. But then Frederick Kelly simply walked the streets and rode the subway, while Garry Winogrand visited the Central Park Zoo. Wall text speaks of coffee shops, hot dog stands, department stores, the kitchen, and the living room with, of course, color TV. A jukebox offers background music on the way in. I entered to bebop and exited to "Please Mr. Postman" by the Marvelettes.

They mark art as interdisciplinary. Early screen prints and assemblage by Rauschenberg, ever a collaborator, hang near high fashion. And he did design dance costumes, which appear on TV along with dancers in motion for Merce Cunningham and George Balanchine. Carolee Schneemann created Newspaper Event for the Judson Dance Company and Yvonne Rainer. Wall text also places artists within movements, like Roy Decarava in Kamoinge photography in Harlem, Norman Lewis in Spiral, and George Macionas in Fluxus and in flux. If Claes Oldenburg had his Store on 2nd Street for plaster household goods and women's underwear, Christo had his storefront, too, tinted red and blue.

Just as much, they argue for art as inseparable from political awareness and its times. Does the black architecture of sculpture for Louise Nevelson reflect slum clearance? I have my doubts, but then she had been evicted from her Kips Bay apartment. Others were already moving into illegal lofts—like Robert Indiana, Agnes Martin, and Ellsworth Kelly on the Lower Manhattan waterfront. Indiana connects the Port of New York to the slave trade, while Kelly derives his white curves from the Brooklyn Bridge. Lincoln Center was underway.

Gender becomes a starting point for women in Pop Art like Martha Edelheit, Marjorie Strider (ooh, that Girl with Radish), and a self-portrait in hacked wood seven times over by Marisol. It is up for grabs with Jack Smith and his film, Flaming Creatures. It drives the blurred photorealism of an enormous eye, by Harold Stevenson, as well. Isamu Noguchi in sculpture adds pungent pink to a woman's profile by Pablo Picasso. Diversity enters again with gestural painting by Miriam Schapiro and Sally Hazalet Drummond. Otherwise, the show leaves Abstract Expressionism behind.

The course of Empire

Race is inescapable, just as in America. The living room TV airs "segregation now, segregation forever," while a giant screen gives voice to Martin Luther King. Surrounding work includes shackles by Melvin Edwards, a racial slur in paint by Mary Stevens, and a triangle of protest leaders by Faith Ringgold. Are they both black and white, and is that a good thing or a sell-out? Foil for Jack Whitten peels away to reveal the police setting dogs on them all. The room ends with The Last Civil War Veteran, by Larry Rivers, in all his misplaced, pathetic glory.

Is anything not relevant? Not to New York, but is that enough for a show? Michelangelo's Pietá at the 1964 World's Fair marks the advent of museum blockbusters. Is this just more of the same? I have not had time even to mention artists as mainstream as Yayoi Kusama, Roy Lichtenstein, Jim Dine, or George Segal. His woman brushing her hair leans forward in what might well be despair. For Dan Flavin and Donald Judd, with his staggered rods in cadmium red and purple enamel, the work extends to Minimalism as well.

Are visitors left Sight Seeing, in the words of a painting by James Rosenquist? The show does, after all, leave New York for the March on Washington and end in Venice. Lee Friedlander turns his lens on Nashville and Baltimore. Marilyn Monroe sings happy birthday to JFK in performance at Madison Square Garden, just when Andy Warhol paints Two Marilyns. But then his Jackie Frieze responds to the Kennedy assassination on national TV. Walter Cronkite may have reassured America, but it took Warhol's Empire, a steady shot of the Empire State Building here in New York, to reassure me.

Are visitors left Sight Seeing, in the words of a painting by James Rosenquist? The show does, after all, leave New York for the March on Washington and end in Venice. Lee Friedlander turns his lens on Nashville and Baltimore. Marilyn Monroe sings happy birthday to JFK in performance at Madison Square Garden, just when Andy Warhol paints Two Marilyns. But then his Jackie Frieze responds to the Kennedy assassination on national TV. Walter Cronkite may have reassured America, but it took Warhol's Empire, a steady shot of the Empire State Building here in New York, to reassure me.

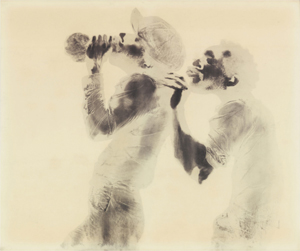

Inclusiveness matters, because textbook divisions do not always make sense. At his retrospective (in a memorable group shot), Rauschenberg posed beside a giant of the past generation, Barnett Newman. Still, the museum is at its best in the rough and tumble of the moment. I could feel it in sculpture by Mark di Suvero like a wrecking tool. I could feel it when Jason Seley demolishes a 1949 Buick, as The Boys from Avignon. It is only a step to a purple automobile for Chamberlain.

Like that opening wallpaper, this New York is ever so familiar today and ever so much the past. Eighth Street was no longer the block where Willem de Kooning held court—and not yet a refuge for me in the bookstores nearby. And it shares that elusiveness with the show. It is both more and less than a biography of Alan Solomon, who died of a heart attack six years after his departure. Would the curator, Germano Celant, recognize it himself? He did not live to see the outcome, although Claudia Gould, Darsie Alexander, Sam Sackeroff, and Kristina Parsons of the Jewish Museum finish the job well.

It has little to do with Judaism—although Boris Lurie, a Holocaust survivor, paints a simple NO. Was there pushback along the way, starting with the Jewish Theological Seminary, whose collection gave birth to the museum? Either way, Solomon lasted just three years. Still, he had not lost his insistence. In Venice, he spoke of Rauschenberg as out "to shock us out of our blindness." He could be speaking of himself.

JAM session

Just Above Midtown opened its "laboratory" in 1974 on the same block as posh galleries—but surely the name, with its connotation of life on the edge, was too good to pass up. So was its shorthand, JAM, with echoes of jazz as an African American art form. As in a jam session, the gallery and its artists were making things up as they went along. If its visibility was low even then, it gave them all a place to be. No wonder many of its highlights came in performance, like David Hammons with his body prints and Lorraine O'Grady in shining armor or as Mlle Bourgeoise Noire. The gallery hardly had an exclusive on either one, but they set the tone for more.

Artists needed a place to hang out and to play. Senga Nengudi sure did, just to open a credit card, when she turned to JAM for pretend validation of pretend income. Goode Bryant herself did, at twenty-five with two sons—and a snapshot shows one of them on the gallery floor. As if in response, Janet Olivia Henry renders The Studio Visit as a comic dollhouse, with Spanky from Our Gang, a sousaphone, and a mattress on the floor. As "Changing Spaces," the show includes no end of slide submissions, interviews, and video recollections. It papers a corridor with eviction notices and more unpaid bills.

Artists needed a place to hang out and to play. Senga Nengudi sure did, just to open a credit card, when she turned to JAM for pretend validation of pretend income. Goode Bryant herself did, at twenty-five with two sons—and a snapshot shows one of them on the gallery floor. As if in response, Janet Olivia Henry renders The Studio Visit as a comic dollhouse, with Spanky from Our Gang, a sousaphone, and a mattress on the floor. As "Changing Spaces," the show includes no end of slide submissions, interviews, and video recollections. It papers a corridor with eviction notices and more unpaid bills.

That opening question is also an accusation: do we really deserve our lack of attention? Yet Goode Bryant took it literally. She was asking what it means to be black or white, and Lorna Simpson curated a show on just that theme. Exhibitions included Native Americans like G. Peter Jemison and Edgar Heap of Birds, Rolando Briseño (a Mexican American from Texas), and Jorge Luis Rodriguez (a light-skinned American from Puerto Rico). They had room for Robert Rauschenberg and for Jasper Johns paired with Hammons.

The very opening show was "Synthesis," and George Mingo painted his Zebra Couple in oil. Among the white interviewers are Nancy Spero and Marcia Tucker, who founded the New Museum. The exhibition has its earnest, sometimes political art, like AIDS Not So Holy by Randy Williams, with a Bible and the face of Ronald Reagan. It has Palmer Hayden in watercolor and Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe in photography, with glimpses of a Harlem window, a doorway, and the subway. More often, though, it is all over the map. Rosemary Mayer has the last word in glassine and cellophane, with October Ghost.

As curator, Thomas (T.) Jean Lax (working with Goode Bryant and Marielle Ingram) can claim some rediscoveries. Valerie Maynard gives linocuts the dark edge of woodcuts, while Noah Jemison makes encaustic and watercolor flow together, and Sydney Blum turns houseflies into an itchy substitute for wool socks. Vivian Browne had her Man in Mountain before her turn to abstraction, Sandra Payne her ink stains as Most Definitely Not Profile Ladies. Norman Lewis is at his best with slim white curves on pitch black, like knife cuts for Arte Povera. So is Maren Hassinger with steel scourges or brooms. One can imagine their toll on a slave.

More often, though, even the best artists have little more than throwaways. That includes works on paper from Suzanne Jackson, Barbara Chase-Riboud, Betye Saar, and Howardena Pindell, hole punch in hand. And that, too, raises questions. For starters, "Are we really that different?" Or was JAM as important for nurturing artists as for art? Artist collectives now with their self-serving exhibitions cannot come close.

"New York: 1962–1964" ran at the Jewish Museum through January 8, 2023, Just Above Midtown at The Museum of Modern Art through February 18.