To the Underworld and Back

John Haberin New York City

Every Ocean Hughes and Jimmy DeSana

You may not think first of New York as a port city, but those who follow art have every reason to remember. They will have trekked to the piers that remain for the art fairs. They have strolled Hudson River Park as a site for summer sculpture today.

They have reason, too, to remember the piers that have disappeared—and gay lives that have disappeared along with them. Until decimated by AIDS, the West Side piers once served as a pick-up joint and a site for cutting-edge art. They have left their traces in dark wood posts here and there along way. Every Ocean Hughes sees in them a melancholy record of lives lost, in photographs at the Whitney. She is celebrating, too, though, in hyperactive videos and performance, enough to call her show "Alive Side." Dead or alive, it is gender bending.

Jimmy DeSana was just twenty in 1969 when he posed nude outdoors amid the trees, but already his camera lingers on the night. These woods are lovely, dark, and deep, their branches touched by ghostly light. Not that DeSana worries much about promises to keep, in retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum, not when there so much else to see—and not when there are so many bodies to reach out and touch. He may seem to have emerged that very second from a disenchanted forest, but it is only his front yard in Atlanta. The single-family houses in other photos are only his neighbors, even if fences, cars, and trucks keep him out, and 101 Nudes are his friends. For him, everything is between friends and everyone is a creature of the night.

Port and portal

Locals have every reason to celebrate Manhattan's far west side. A walk uptown from the Battery, at the island's southern tip, offers fresh air and changing scenery from more than fifty years of gentrification. It runs north from Battery Park City, past the new Whitney itself, Chelsea galleries, the High Line, and the eyesore of Hudson Yards. I injured myself good on a run up to the George Washington Bridge and back from Riverside Park on the Upper West Side. Right across from the Whitney, David Hammons has added his tribute to the piers, with the outlines of a warehouse that once stood deserted but alive. Just a block north, Barry Diller has added greenery and an ego trip, with the floating mushroom of Little Island.

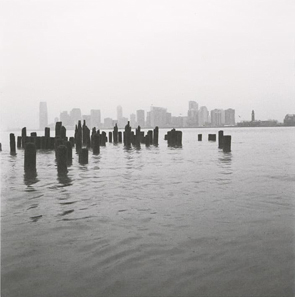

The piers, though, were first a place to take risks, and Hammons commemorates Gordon Matta-Clark, who took a torch to that lost warehouse, letting in the light. Gay men took serious risks, too. The AIDS crisis put an end to that even before developers moved in. Art was dealing with the loss all along, in photographs and other work by Alvin Baltrop, Peter Hujar, and David Wojnarowicz. Hughes turns her lens instead on absence, in black and white. One might never know that the neighborhood had a life of its own.

The photos seem uncomposed, just as the stumps pop up in the water where they will, while echoing the ghostly skyline in the distance. Awkward but insistent, they turn an eyesore into a memorial, and the weathered wood serves the medium's gradations of gray. They stood as emblems of decay itself at the 2010 Whitney Biennial. They are also understated, a word that may not always come to mind with Every Ocean Hughes. Sure, the Hudson runs out to sea, but she wants to encompass every ocean, and she creates her own trash myths to help. If the photos ever seem a bit too restrained, her multimedia is anything but.

Is there, as she says, a "queer perspective" on death, like the "Queer Cut Utopias of Xiyadie in China? If so, that perspective is happily over the top, and one of two videos, Help the Dead, is a musical—set in an artist's studio, like her contribution to the 2010 edition of "Greater New York." The title of the other, One Big Bag, could well be self-reflexive. It is, though, merely obsessive, and that bag is the tool kit of death doula. Hughes herself, born in 1977 as Emily Roydson, was trained in death care. She packs her very own "mobile corpse kit."

But wait: a doula assists not in death but in birthing, right? Maybe, but the dying deserve a midwife into the next world, too. With an aging population and debate over assisted suicide, the only question is how much care. Yet even that underestimates her ambition and the madness. In performance, as River, the community makes round-trip visits to the next life.

The show begins in the often-overlooked space outside the education department and theater, like the photos in "Time Management" just before. It could easily have continued there or in the lobby gallery, with the videos on two screens and a space for performance. One might expect no less from the exhibition wall text, which places new media first—and you may find yourself looking around for more. I know I did. The curator, Adrienne Edwards with C. J. Salapare, chose instead a staggered schedule (and the exhibition Web site has added ticket information since the opening). Forgive me, then, if (at least so far) I have caught only the photos and hour-long performance.

The hard part

River refers to both the site of the Hudson River piers and the passage to the underworld. Hughes, though, is anything but otherworldly, and she cannot stop for death. Corpse care, she argues, should be at once "practical, political, and spiritual." As a voice puts it in her performance at the Whitney, "we don't do death well anymore," and the work nears its end in unveiling a "corpse kit" and training the audience to be patient with the dying and the dead. First, though, she has a question: what is dead?

For Hughes, death is a "complex social choice"—the choice of whom to remember, whom to harm, and whom to let die. That out of the way, she can get down to cases. "We need thirteen people," say the performers (neither of them the artist), but not to speak for themselves alone. They take part in a first-person narrative of facing death, as nurses and loved ones. The point is to "normalize death," and here that entails also normalizing queer, while remaining "weird." Audience members do not always match the age or gender of their parts.

For all my misgivings, the Whitney's theater suits them well. It is intimate enough to embrace a double circle of chairs without a curtain or a stage, where the audience can feel close and performers can circulate. Yet it is large enough for a high ceiling and tall windows running the length of the west wall, facing the Hudson. And there one sees not dead stumps, but distant lights and a new pier under construction for signs of renewal. If that sounds as hopeful as the promised passage to and from death, I chose a late afternoon performance, sitting through sunset (a dramatic one) and leaving in the dark. I still had time to catch an opening in Chelsea for an artist already dead.

From an unseen distance, one hears the tolling of bells, for sea traffic or for the dead. At the center of the circle, one sees music stands and shrouded forms, in raw colors and black stripes. Someone might have covered standing children and the lumpy outlines of mourners and the dead. Removing the shrouds reveals helium balloons rising from glass bowls or holding the fabric aloft. At the show's climax, one last shroud removed, a man seemingly rises from the dead. Yes, a spoiler, but you saw it coming, right?

The music stands hold not scores but text, but the man (in basketball uniform) leads a dance to a pop tune. Before and after, the lead performers sing, rising from a simple chant to full-blown harmonies. "This is about you," they warn up front, "and about me and about you," but the universal threat of death gives way to a celebration. Is that a little much? To face death, Hughes insists, one must get past the euphemisms and the paperwork, but the euphemisms will not let go. "Being alive is the hard part."

When the narration speaks of the present day forgetting how to die, it is downright nostalgic. It may be too harsh on the present as well. Did the funeral industry really invent embalming and hollow ceremonies? The pyramids, anyone? At the very least, I wish that she had cut the pop song and dance (a little too close to the communal ending of Hair) and gone directly to the resolution in chant. And yet, as I age and the pains set in, I know what she means about being alive.

Creatures of the night

Jimmy DeSana lived fast, in a career cut short by AIDS, and he worked fast as well. So many nudes, so little time? No sweat, and the Brooklyn Museum conveys his pace with clusters of photos, display cases, and clippings. The more than two hundred works in its modest lobby gallery fly right past. Collaborators turn up often as well, and he took a break to star in a film by Michael McClard, Motive, as a psycho killer. He had to move fast, because he acted on impulse, and his best impulses drew him to people.

They brought him to New York in 1973 and to portraiture. Not that he had an eye for pageantry, personality, or psychology. He was not a fashion photographer either, but he had a gift for finding people who matter and fitting right in. He became known for the punk and No Wave scene, and his subjects include Debbie Harry, David Byrne, and Laurie Anderson. He became known, too, as an LGBT+ photographer, and he exchanged work through the Queer Mail Network with such artists as General Idea. And the circles only widen.

He loved popular culture, but he rarely quotes its images. More often, he sees it through the eyes of cutting-edge artists, with a special fondness for Andy Warhol. Like DeSana himself, they are artists for whom highbrow and lowbrow are one and the same. That includes Fluxus, and he photographed Nam June Paik and Yoko Ono dressed not for the studio, but for success. It includes Laurie Simmons of the "Pictures generation" and Ray Johnson, who moved easily between street photography and movie stars. He got to know Gregory Battock, whose first critical anthology, The New Art, appeared in 1968 and had already become a textbook.

He loved popular culture, but he rarely quotes its images. More often, he sees it through the eyes of cutting-edge artists, with a special fondness for Andy Warhol. Like DeSana himself, they are artists for whom highbrow and lowbrow are one and the same. That includes Fluxus, and he photographed Nam June Paik and Yoko Ono dressed not for the studio, but for success. It includes Laurie Simmons of the "Pictures generation" and Ray Johnson, who moved easily between street photography and movie stars. He got to know Gregory Battock, whose first critical anthology, The New Art, appeared in 1968 and had already become a textbook.

Fitting in, though, was never enough, not when he still belonged to the night. More and more, he looked to photography to create a sexual identity. Who needed portrait photography when there was so much else to male and female bodies than faces? Again, though, he was not into either/or. He got to know Sylvère Lotringe, the editor of Semiotext(e) who had earned a living as a sex worker. And his changing subject brought him to new resources for photography as well.

His Suburban series introduces color and a larger format. Tungsten lights and gels make those colors as ghostly as his early woods, casting shades of purple, pink, yellow, and green. A pink body posed on red traffic cones approaches a mannequin or a blob. He also starts to see naked bodies through their props, like upside-down chairs and extension cords, as oblique indicators of S&M. He collaborates with Terrence Seller on The Correct Sadist, and another series, "Submission," lends its title to the exhibition. In his sole video, Double Texture of 1979, the body emerges and disappears again amid curtains, dogs, and shaving cream.

One might see only a casual affair, but a continuing one all the same. When DeSana first closes in on body parts, the curator, Drew Sawyer, sees the sheer speed of paparazzi still in search of celebrities. The title Suburban recalls his early interest in postwar homes. How good anyway are photos that fly so quickly past, giving out well before his early death in 1990? What if they never do confront the AIDS crisis with the frankness of Nan Goldin, David Wojnarowicz, and Robert Mapplethorpe? Still, his creatures of the night manage to express his desires and a viewer's fears.

Every Ocean Hughes ran at The Whitney Museum of American Art through April 2, 2023, Jimmy DeSana at the Brooklyn Museum through April 16.